Kinnickinnic Avenue is a bustling purgatory. Marred by industry and pockmarked with vacant lots, Kinnickinnic runs north and south between Milwaukee’s trendiest neighborhood—the Third Ward—and up-and-coming Bay View. On any given day you might see men and women carrying trash bags filled with crushed aluminum cans or piloting grocery carts brimming with their worldly possessions under leafless vines that droop from telephone wires. Today a couple argues on a street corner while their baby cries, strapped to her stroller. An ambulance races past, siren wailing into a slow Doppler fade that gives way to a bush full of nesting sparrows erupting into chatter. Upended blaze-orange construction cones point wayward past cement manufacturers, auto salvage yards, and other businesses whose signs have outlasted their customers by a full half-century. Manholes punctuate litanies of uneven sidewalk. Concrete underpass walls painted a scrim of white half conceal scrawled anarchies of graffiti. Eight acres of blighted brownfield, scorched, fenced-in, for sale.

Walking this wide empty stretch of road is one of the city’s dispossessed. His name is Jerry.

Jerry scours alleyway dumpsters, seeking the promise of aluminum that pays 82 cents a pound. Today he is hauling the mother load: two 24 by 30-inch copper plates, bungeed together onto a dolly that lurches behind him as he trudges up Kinnickinnic, a 40-ounce bottle holstered in a crinkled brown paper bag at his side.

Jerry scours alleyway dumpsters, seeking the promise of aluminum that pays 82 cents a pound. Today he is hauling the mother load: two 24 by 30-inch copper plates, bungeed together onto a dolly that lurches behind him as he trudges up Kinnickinnic, a 40-ounce bottle holstered in a crinkled brown paper bag at his side.

Jerry doesn’t walk, he galumphs; each step an unsure progression over uneven sidewalk. He wrestles with the heft of his copper score, pulling the dolly as if a drudge, fingertips confessing cracks stained by street and grime—the weather of a man both breaking and broke.

Moving through the exhaust of a passing Buick, Jerry stops a moment outside a Laundromat to exchange rare words with a college-age beauty. His breath a miasmal stew of hops and loam, the young woman recoils slightly as he opens his mouth to speak.

She executes a quick survey of Jerry’s burden: Etched onto one copper plate is a cowgirl, donning a long-sleeve checkerboard midriff top that reveals a tattooed creature of some sort (a cat? a Tasmanian devil?), peeking like an inside joke from the waistband of her pants. She holds the reins of a horse whose spots are more abrasion than Appaloosan. Its belly is a distended anomaly, and beyond its withers a jejune rattler coils in the cool shade of an oddly perfect cactus with three arms and a crown.

Plate #2 bears the portrayal of another woman, crudely rendered, with eyes like halved avocados. Rife with tattoos, she stands in high heels on the back of a dolphin blowing slits of water through its blowhole. A fresh layer of scratches covers a pair of discordant, annular breasts belying a denuded, more salacious earlier version made modest at second thought. The woman’s tattoos reveal an affinity for gambling (dice), seafaring (anchor), stars, skulls, hearts, and doves … and “Mom.” She holds an open pack of Lucky Brand cigarettes, one of them dangling unlit from her overemphasized lips. And then there’s her hair, reminiscent of a harpooned monk seal, blacker than a raven’s reflection in oil.

There is, in fact, an eerie quality to these etchings—each of them struck through by a giant, irrevocable X—on their way to meltdown at Mill Valley Recycle Center, Jerry’s terminus.

The woman Jerry’s talking to regards him: black leather jacket with cloth hood, zipped to mid-chest; unbuttoned button-down shirt with tee underneath; black jeans, faded gray; scuffed steel-toed work boots; ash-brown hair peeking from the circumference of a baseball cap that reads Zad’s. The corners of his mouth are sinkholes, sucked inward toward an abutment of toothless gums, framed by a weeks-old beard that manes a face set with deep wrinkles that stretch like withered roots from the trunk of his nose.

.jpg) Unprompted, she says to him, I’m an artist, too, and offers a few additional niceties. Nodding, Jerry takes a long pull from his bagged bottle, and the two of them finally depart in opposite directions.

Unprompted, she says to him, I’m an artist, too, and offers a few additional niceties. Nodding, Jerry takes a long pull from his bagged bottle, and the two of them finally depart in opposite directions.

The copper plates will net Jerry a cool $70 once he arrives at Mill Valley. What Jerry doesn’t know is that these same two copper plates cost Milwaukee artist Charles Dwyer nearly four times that when he bought them new. The reason Jerry doesn’t know is because Charles has chosen not to tell him.

Jerry Pfeil is an artist—albeit, an accidental one. And the etched plates he’s about to have melted down aren’t the fruit of some triumphant dumpster treasure hunt. They are the work of his own hands.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

“He said he’d pay me back,” says Charles Dwyer, sinking into a chair made from reclaimed wood. His Bay View studio—which also doubles as his home—is a miniature museum, a lamp-lit private gallery that’s been dubbed “The Tainted Loft” by friends who congregate here to watch occasional Brewers games and Monday Night Football. It’s populated by menageries of inspiration, revealing a telling bent for the arcane and the kitsch: vintage pens rubberbanded to a piece of white cardboard; an intact beehive still attached to its tree branch; a homemade end table fashioned from a piece of authentic Lake Michigan driftwood, detritus lugged up from the beach one morning while out walking Napoleon, Charles’s shaggy, black Bouvier Des Flanders.

When I ask him about a piece of plyboard crowded with glued-on white sew-through buttons, upon which has been painted the words, Home Sweet Home, Charles says, “Jerry painted that one.”

Charles is telling me the story of how he forged an unwitting friendship—and ultimately a collaboration—with a man he met in the alley behind his studio one hot June afternoon in 2007.

Charles is telling me the story of how he forged an unwitting friendship—and ultimately a collaboration—with a man he met in the alley behind his studio one hot June afternoon in 2007.

“I saw him digging in my dumpster,” says Charles.

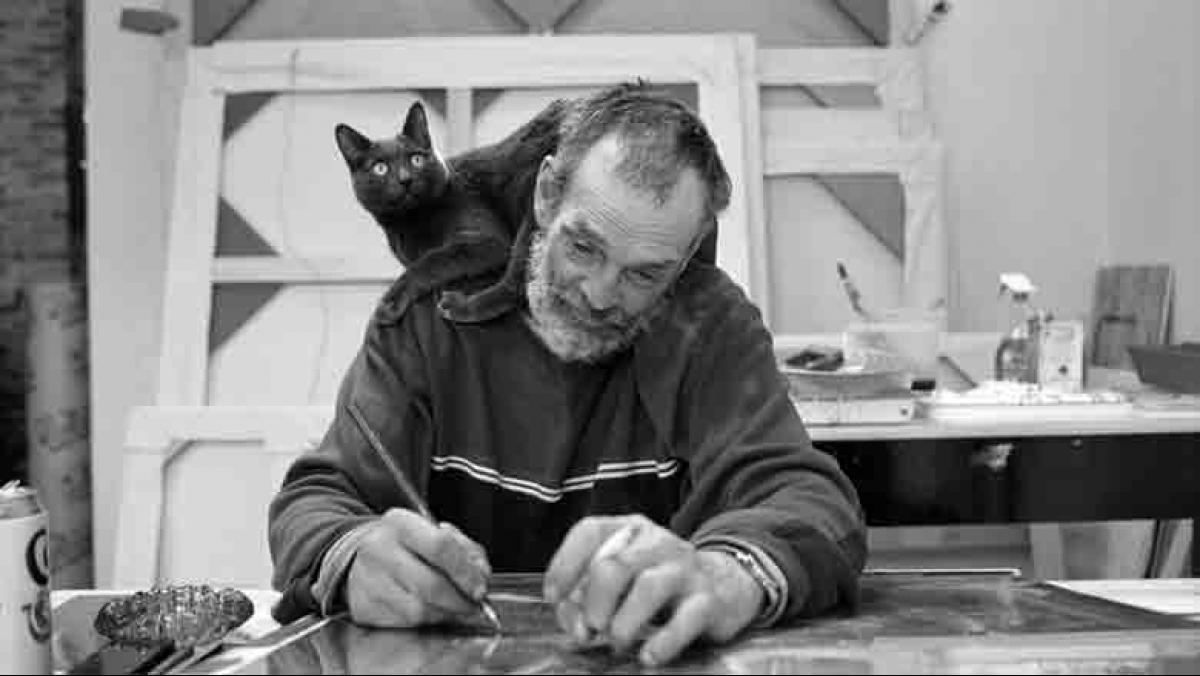

Charles, whose friends call him Chuck, looks like a guy who makes art for a living. An artist of international repute, Charles’ work hangs in major public, private, and corporate collections throughout the United States, Munich, Germany, Barcelona, and Spain. Today he’s wearing blue jeans and a white long johns top, sleeves bunched above the elbows, with light brown work boots paint-splashed in kaleidoscopic colors. He adjusts his horn-rimmed glasses and welcomes Jenny, an attention-seeking Burmese cat, onto his lap. It purrs as another, more avaricious cat—Billie—stalks a fly. “They’re sisters,” Charles says, visibly entertained by the spectacle of predation. “Get ’iiim,” he goads, before returning to the subject of Jerry.

“It was June, really hot. I hadn’t seen him before, but he looked interesting to me. Like he had more to him than a guy digging in a dumpster.”

Acting on what he describes as a whim of goodwill, Charles walked over to him.

“ ‘Hey, tell you what, here’s five bucks,’ ” I said to the guy. “Go get something to drink. Some water to make your day a little easier. ”

”

And that’s how it began. With the passage of a five dollar bill from one hand to another. And then, later, a knock on Charles’ door.

“Hey, man, can you spot me another five?”

And then another knock.

“Hey, man, can you spot me a few more?”

And another.

“Hey, Chuck, can you spot me … ?”

Knock after knock—month after month—Jerry returned to Charles’ door, asking for money, for a flashlight, for food. One day, Jerry asked for a space heater. He’d been staying with an old buddy a few blocks up the street, living out of his breezeway, and the encroaching Wisconsin autumn meant foggy florets were beginning to bloom from Jerry’s mouth with every breath. To keep warm at night, the space heater was all he had. But every night, it would overload a circuit and blow a fuse. Naturally, as this persisted Jerry’s friend started blowing fuses of his own. Eventually he kicked him out.

Homeless, jobless, nowhere to stay, Jerry did some reconnaissance near the train tracks just north of Lincoln Avenue and dropped anchor in an alcove between two buildings, constructing a lean-to under a large tree for shelter.

The next day, he knocked on Charles’ door again.

“It got to the point,” Charles says, “where I lent him about seventy-five dollars. He told me he’d pay me back, and I never really expected that to happen. But if you say you’ll pay someone back, you’ve got to at least make an attempt to pay them back. It’s just how society works.”

Knowing his reimbursement wouldn’t come in the form of cash, Charles brainstormed other ways Jerry might be able to settle his debt. Finally, he came to one. “I fantasize about the life of hobos,” says Charles. “I’ve always liked them. I like walking my dog and seeing the trains and the graffiti and imagining train jumpers and the lifestyle they must lead. It’s romantic to me, in a sense. So, I asked Jerry, ‘Have you ever thought about keeping a sketchbook?’ ”

Charles’ idea was, You fill up a sketchbook, I give you a hundred bucks. Not that Charles needed the money. It was simply a matter of principle: I give you something, you give me something in return.

“He didn’t want anything to do with it,” says Charles, “didn’t want to be burdened by something he had to carry, by something he had to do. He’s a guy living on the street. He goes canning. What’s he gonna do with a sketchbook? So … no sketchbook.”

Charles reasoned, if Jerry wasn’t willing to carry a sketchbook, maybe he would come into the studio and do some art there instead?

“At the time,” says Charles, “my daughter was just starting college and taking a printmaking course. So I hired some guys and we got this giant press set up. It had been in pieces in my studio for six years. I thought, Jerry could use this, too.”

At first, Jerry spurned the idea. He was, after all, no artist. In fact his hands hadn’t traced a single image on a sheet of paper since who knows when, grade school maybe? That was nearly forty years ago. But an alcove between buildings can be a wildly windy place in Wisconsin, especially with winter approaching. And when winter does come, what then?

A knock on Charles’ door.

The voice from outside asked, “Hey, Chuck, man. You still wanna do some art?”

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

“I think maybe it was the word copper that caught his attention,” Charles says, pausing to light an Export-A Full Flavour cigarette as Jenny leaps from his lap to join her sister in hunt for the fly. “He probably thought, Copper … Hey, I can recycle these!”

Charles lifts himself from the belly of his chair to French-press us some coffee. He pours two unusually small mugs—“It’ll be potent,” he says—and, handing me one, resumes talking only to be interrupted by the tenor of Napoleon’s loud bellow. Some sound has drifted through the open studio window and riled him up. “I knew all along that I wanted to have Jerry work with copper,” continues Charles. “There are no erasers. It’s just the line. It’s as honest as you get.”

Charles lifts himself from the belly of his chair to French-press us some coffee. He pours two unusually small mugs—“It’ll be potent,” he says—and, handing me one, resumes talking only to be interrupted by the tenor of Napoleon’s loud bellow. Some sound has drifted through the open studio window and riled him up. “I knew all along that I wanted to have Jerry work with copper,” continues Charles. “There are no erasers. It’s just the line. It’s as honest as you get.”

When I ask Charles what those first few days in the studio were like, he pauses a moment in silent reminiscence, a flash of nostalgia manifesting itself into a grin that grows exponentially up his cheeks until it’s a full-fledged smile. He raises his mug to his lips, takes a sip from the strong brew that’s only a few degrees shy of scalding, then sets it back down upon a coaster. Crossing his legs, Charles lights another cigarette and exhales, the echo of a smile still extant on his face, the nostalgia still thrumming.

“I’d love to hear Jerry answer that question,” he says.