Stacks of artwork, both finished and unfinished, overflow William Weege’s printmaking studio in rural Arena. Piles of coarse paper clutter the tables on either side of an imposing printing press, while prints from the many decades of Weege’s career rest in drawers or hang on racks. Some are framed and hung, others lean against the walls. The artist worked in an accretive process, and many pieces have been printed, painted on, and further built up with wooden or cardboard shapes attached to their surfaces. The prints seem to wait for more to be done to them, or maybe for something to be taken away. Perhaps even if the artist were still here to finish them, these prints wouldn’t be perfected but simply halted at a stage where the eye hangs on them best. There’s a sense of mutability about Weege’s art, as if the form we see might still be on its way to something else.

Weege, who died in 2020, was a groundbreaking printmaker. His early work, made during the tumult of the Vietnam War, expressed overt political themes through strong layers of graphic imagery. Weege’s work after the 1970s, however, moved through several phases of abstraction. Created with bold exuberance, this later work is so far from what you might think of as traditional printmaking that it’s hard to know what it is or how to take it in.

At Weege’s studio I’m drawn to a white shadow box leaning against the wall, where silver thumbtacks lightly hold together an assemblage of small paper constructions. The collage/sculpture looks casually made, as if it’s ready to be rearranged or even torn apart. “That’s one of Sam’s,” Weege’s widow, Sue Steinmann, tells me, referring to the artist’s longtime collaborator, the painter Sam Gilliam. But when we look closer, we see that in fact both artists have signed the piece.

It seems unusual to see two names on a work of art, but it’s a marker of how deeply entwined Weege was with the artists he worked with. He collaborated with Gilliam, one of America’s premiere living abstract painters, for over fifty years. Weege had a similarly close working relationship with abstract painter Alan Shields. Gilliam, Shields, and many other artists flocked to Weege’s Jones Road Print Shop and Stable in rural Barneveld during the 1970s. In the mid-1980s, Weege moved to a hilly, secluded property in Arena, another small town outside of Madison, and a few years later he founded Tandem Press at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Tandem took up Weege’s vision of printmaking as a closely collaborative art form, and today the press brings artists from all over the world to Wisconsin to explore and expand the art of printmaking.

Weege was a world-class artist, but he didn’t feel the need to live in New York or Los Angeles. The art world happily came to him. Weege’s deep, lifelong engagement with the Wisconsin landscape also kept him here. He not only worked outdoors, inviting the elements to transform his art, but he spent over thirty years restoring the native prairie and oak barrens at his and Steinmann’s Arena property, Rattlesnake Ridge. This is no coincidental setting, but a particular landscape that infused his abstractions and, in turn, benefited from the same vision and technique Weege brought to his art.

• • • • •

William Frederick Weege was born in Milwaukee in 1935 and grew up in Port Washington, where his father was a mechanical engineer. Weege, too, studied engineering, first at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and then at UW–Madison, where he later switched to city planning. While he mastered advanced photo printing through a job at a commercial printing firm, Weege became increasingly drawn towards drawing and painting. When he returned to UW–Madison to study printmaking and joined the MFA program, Weege was already in some ways more capable than those who would teach him.

In the complex mechanics of printmaking, images on the plates are reversed and each color application requires a different plate. Printmakers consider how each layer affects the others, and the combination of pressure, ink, and plate creates many variables to be mastered or exploited. During his MFA studies at UW–Madison, Weege continually pushed at the technical limits of printmaking, striving to create something completely new out of the notion of layer.

During the late 1960s, massive demonstrations against the Vietnam War shook the UW–Madison campus. Weege drew on his political passion and artistic skill to create posters for these protests. His posters became so popular that people often stole them as soon as he put them up.

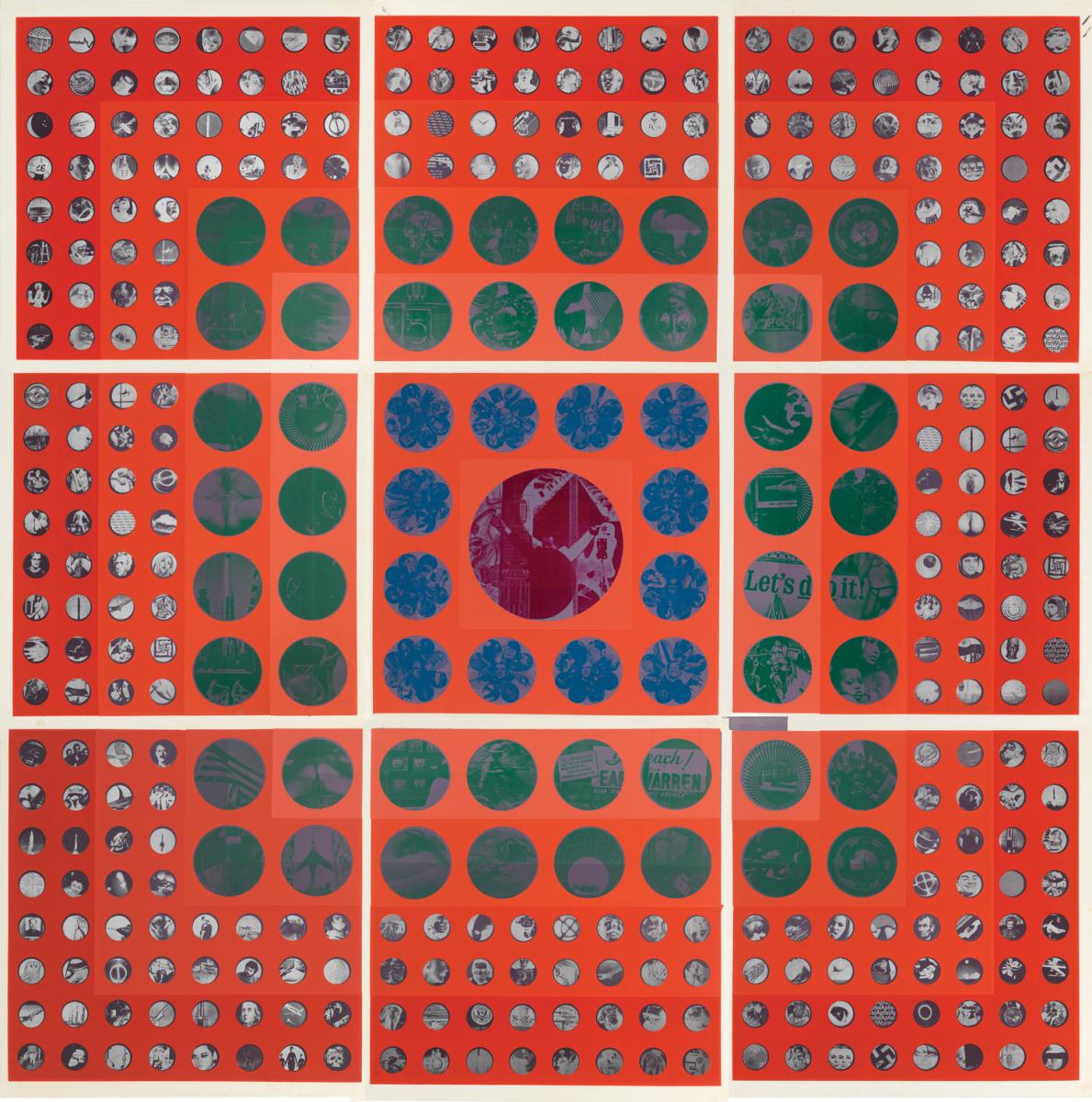

Weege drew on themes explored in these posters for his MFA thesis, a series of 25 provocative prints titled Peace Is Patriotic. These deeply political works embedded photos of nude women, body parts, guns, and skulls into brightly colored geometric patterns. The Peace Is Patriotic series was hailed as an instant sensation. On a class trip to New York with his major professor, Warrington Colescott, Weege sold the entire Peace Is Patriotic portfolio—all 25 prints—to the Brooklyn Museum, the New York Public Library, and the Museum of Modern Art. The acquisition of his portfolio by these institutions was major recognition for an artist just at the start of his career.

In 1970 Weege was selected to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, a renowned international art exhibition, where he headed an experimental printing workshop. When he returned from Italy after a year of working with artists from all over the world, Weege could have gone almost anywhere. Yet he chose to stay in Wisconsin. He became an art professor at UW–Madison and lived for the rest of his life in rural Iowa County, first in Barneveld and later in Arena.

• • • • •

Weege and Steinmann, his second wife, bought their land in Arena in October 1984. They wanted enough space for Weege’s printing studio and for Steinmann, a horticulturist, to set up her nursery business, Sand City Gardens. Because they’d seen the property only in the dormant season, they had no idea what surprises it held. When spring came, one field was “purple with birdsfoot violet,” recalls Steinmann. Native grasses and flowers prospered, as much of the hilly area had not been entirely altered by agriculture.

At this point, she and Weege didn’t yet own the stretch of remnant prairie higher up on the hilltop, but the owners allowed Steinmann to pick flowers there for the bouquets she sold at the Dane County Farmers Market. At the market, her bouquets caught the attention of Rich Henderson, a research botanist at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and leader in prairie conservation and restoration through his work with The Prairie Enthusiasts. He stared in consternation at a flower in one of her arrangements and asked Steinmann where she’d gotten it. She told him this plant, rattlesnake master, grew in Arena. “No,” she remembers him saying. “It doesn’t grow there.” Steinmann invited Henderson to come and see for himself.

After meeting Henderson, Weege and Steinmann became deeply involved in prairie restoration work around Iowa County. Through The Prairie Enthusiasts and other conservation groups, the couple learned about the needs of various prairie ecosystems and how acreage that had been plowed and farmed, or that had become overgrown with trees and shrubs, could be brought back to an open state. With regular seasonal burns and removal of woody plants, the endangered native grasses, flowers, insects, and birds could return.

Weege and Steinmann discovered that Rattlesnake Ridge was home to many rare plant species, as well as snakes, foxes, deer, and even bobcats. They felt an obligation to foster the native plants and wildlife that flourished in the region, and the only way to do this was to learn to manage and protect the land. When land adjacent to their original parcel became available for sale, Weege and Steinmann bought it to keep it from being developed for housing or cattle grazing. They then gave around 50 acres in trust to The Prairie Enthusiasts. The ridgetop prairie where the rattlesnake master grows is today a public-access nature preserve of almost 100 acres.

Weege and Steinmann found that they had more than remnant prairie on their property. Opening out of Weege’s studio and Steinmann’s greenhouse is one of the rarest ecosystems on earth: an oak barrens. Formed on a layer of windblown sand that’s in some places 80-feet deep, the barrens’ dune-like soil retains very little moisture and holds scant organic matter. It’s almost pure silica. Nevertheless, some two-hundred species of native plants are able to thrive in these demanding conditions.

While there are oak and pine barrens in Michigan and Indiana, Wisconsin is home to several barrens in the unglaciated soils of the Driftless and along the lower Wisconsin River. Still, the one that Weege’s studio looks out on is exceptional, dominated by one massive, clonal Pennsylvania sedge. This weeping grasslike plant flows like waves across the beachy soil in a long, low repeating pattern. In most environments, Pennsylvania sedge peeks out at ground level, with showier flowering plants rising above it. But in the barrens on the Weege property, Pennsylvania sedge is the star attraction, its undulations drawing you on as you follow the path up to the ridgetop.

Like prairies, barrens are dependent on fire and must be burned regularly. And, like prairies, barrens in Wisconsin have been severely reduced by plowing and grazing since the 19th century. Steinmann remembers some prairie restoration consultants coming to their property and viewing the barrens with dismay. She and Weege were advised to try to reseed it with prairie plants. Ecological thinking seems to have shifted, though, and today the barrens are recognized as distinct from prairie, and worthy of preservation in its own right.

“Bill and I always loved the barrens,” Steinmann says. “It’s a more subtle beauty.”

• • • • •

Weege’s art changed considerably over the 1970s, when he discontinued working in the graphic style that made Peace Is Patriotic so provocative. While these prints gained him much acclaim, Weege endured sharp criticism as well for his use of nude photos of women. Once, a viewer took a razor to one of his prints on display at the Whitney Museum in New York, presumably because of its title: Fuck the CIA.

“I got tired of it,” Weege recalled in Progressive Printmakers: Wisconsin Artists and the Print Renaissance, a chronicle of the early days of printmaking at UW–Madison by Warrington Colescott and Arthur O. Hove. The negative attention wore on Weege. He began making his own paper and moved into abstract work that was still provocative, but in a less identifiable way.

Whether the work was abstract or figurative, Weege pushed at printmaking’s cutting edge. John Corbett, an art scholar who runs the Chicago gallery Corbett vs. Dempsey, describes the Peace Is Patriotic series as “impossible, impossible prints” due to their technical bravura. Robert Cozzolino, a curator at the Minneapolis Museum of Art, explains how in his abstract work Weege “used all of the technical tools available to conventional printmakers” and then broke boundaries by deliberately “doing what printmakers are not supposed to do.” The dense two-dimensional layers of Weege’s early work evolved into collage, assemblages, and riffs on paper itself.

Weege made massive pieces, almost too big to hang, in the 1980s. He also made small woodcuts in the 1990s with explicit environmental themes. Though the prints of this era took a sharp turn from the sprawling pieces he’d done earlier, the same spirit of play infused all his work. “A lot of it, I don’t know what’s going to happen,” Weege told the Milwaukee Journal in 1994. “I create situations where you can have a happy accident.”

An outstanding example of Weege’s abstract work is easily accessible in the Hamel Music Center, the new music school auditorium on the UW–Madison campus. Malcolm Holzman, the New York-based architect of the Hamel, had known Weege since the Jones Road days in the 1970s. After running into Weege at an exhibition of his work at the Pace Gallery in New York in 2016, Holzman hit on the idea of transforming a Weege print into wallpaper that would cover the interior walls of the recital hall. It took several years, and a lot of back and forth between Weege and the architectural team to finalize the pattern, which was taken from one section of a 1987 print called Like a Rolling Stone. The result is a rich red ground pulsing with layered colors and black geometric shapes.

Holzman joked with Weege that the wallpaper would be “his biggest installation,” as if that might be a let-down for an artist of his stature. In fact the Hamel wallpaper is stunning, and a wonderful public legacy for Weege. Some of the same qualities that made Weege’s Peace Is Patriotic prints so evocative are here as well: the strong colors, the depth and complexity of the layers, and the rhythmic repetition of forms. It’s also possible to see this as a version of the dramatic landscape of the barrens: the repeated waves of the Pennsylvania sedge against the light-colored soil, the criss-cross of other shapes and blooms as plants come in and out of season. This is what Weege looked out on over his decades of creation in Arena.

• • • • •

He was always outside,” Steinmann says, showing me the deck outside the studio where Weege and Sam Gilliam worked every summer. “The elements were always really important,” she explains. Weege would set his homemade paper outside to dry and “sometimes it got rained on, or the dogs would run through it. He always said, ‘It doesn’t matter, it’ll dry.’ ”

The elements were vital to Weege’s work. Art scholar John Corbett sees a planar quality in both his Peace Is Patriotic series and Weege’s later abstractions: his prints tend to lack a central focal point and are spread across the visual field. Architect Holzman, too, sees an aspect of landscape in Weege’s work. His prints are “full of pattern and texture and flowing forms,” he says. Though you won’t see representations of plants in the abstract prints, the spreading multiplicity of elements, with repetition and variation, competing shapes and colors rhythmically contained, are reminiscent of the vitality of the rural lands where Weege chose to live for the majority of his life.

Weege brought his sense of joyful experiment into his land preservation as well as his art. Jeb Barzen was director of field ecology at the International Crane Foundation in Baraboo for almost 30 years and worked closely with Weege and Steinmann on conservation in the Arena area. Barzen saw in Weege’s approach a willingness to live with uncertainty. To restore the land, you have to commit to “a process where you don’t know what the endpoint is,” says Barzen. It requires the balancing of thousands of interconnected species, as well as other complicating factors. “Bill rarely talked about his art with me,” Barzen says, recalling their conservation work. “Yet I realized I was experiencing it.”

It’s also clear how much Weege loved the land he lived on. He traveled all over the world, for his art and in the pursuit of his other passion, fly fishing. Weege had been as far as Siberia and Patagonia, and he took frequent trips to the Caribbean. Nevertheless, Steinmann says, “he preferred walking on our own property to anything else.” He took joy in what they’d accomplished, and hiked or skied the land in all seasons. Steinmann likes to visit different natural areas, and she would sometimes drive to try out a new trail. Weege didn’t understand it. “Why don’t you walk here?” he’d ask her. “There are plenty of places to walk.”

Weege, along with his collaborators at Jones Road and Tandem Press, pushed American printmaking into new realms. A writer for ARTnews once described Weege’s Jones Road as “a workshop in which anything is possible, at least until it has been attempted.” Steinmann says he approached everything in this spirit, whether it was printmaking or a prescribed burn. He went into any project with vast enthusiasm and continuous delight in solving problems. She remembers a recurring pattern when Sam Gilliam came to work with Weege in the summer: “They took everything too far.” The two of them would go past where they intended, “then they’d figure out how to bring it back, and they’d laugh about it. That was how he did everything.”

Weege’s daughter Jenny says of the artists who came to Jones Road when she was young, “People wanted to work with my dad because he was such a great technician. He could always come up with different ways to do things. Sometimes the artists wouldn’t know how to do what they wanted, and he could help them.” Jeb Barzen explains that Weege’s contributions to conservation followed suit. “It’s important for people to do this work, even if you don’t know how.” Inspiration and collaboration, uncertainty and imperfection: for Weege the process was more important than the result.

Weege was diagnosed with brain cancer in August 2019. Though he saw his wallpaper installed in the recital hall, when the Hamel Music Center had its grand opening in fall 2019, Weege was too ill to attend. In September 2020, when it became clear Weege’s cancer would take him, hospice care set up a bed for him in the living space of his studio. Though there’s a house on the property, the living room of the studio was Weege’s favorite spot to relax, Steinmann told me. She and I sat there talking, two months after he died. Birds never stopped their flapping and chattering outside the window. Inside, several six-foot snakeskins, shed by local bull snakes, hung in the light.

With Weege confined to bed and in decline, Steinmann had continued to manage the land. She still had a lot to do. Since she retired from her nursery business in 2016, Steinmann felt like she was finally getting going on Rattlesnake Ridge. While Weege lay in bed, weakening from his disease, she organized a volunteer work party to prepare the prairie for winter rest. “The day he died, we were burning,” she told me. “The last thing he would have smelled was smoke.”