Six years ago, an attack left Andy Fabino blind. While visiting his family in Chicago, Fabino was beaten so severely that he was in a coma for fourteen days. In addition to leaving him physically debilitated, the beating damaged Fabino’s optical nerves beyond repair. He spent almost two months recuperating in the intensive care unit at West Suburban Hospital in Oak Park, Illinois.

Fabino’s recovery was incredibly difficult. “I had to learn how to walk and how to use my hands and arms again,” he remembers. “And then, I had to deal with the fact that I was blind.”

But today, thanks to an innovative device developed here in Wisconsin, Fabino knows when his one-year-old granddaughter comes toddling into the room.

“I’ve never seen her with my eyes but when I put the device on, I feel her little hands and little round face. … I know it’s my granddaughter Aniyah,” he says, his voice rising with pride. “Can I see her? No. But I can feel that she’s there.”

The way Fabino can “feel” objects and people around him is through the BrainPort V100, a vision-aid device developed by a Middleton company called Wicab Inc. The BrainPort V100 helps profoundly blind patients with orientation, mobility, and object recognition through electro-tactile stimulation to the tongue.

The way Fabino can “feel” objects and people around him is through the BrainPort V100, a vision-aid device developed by a Middleton company called Wicab Inc. The BrainPort V100 helps profoundly blind patients with orientation, mobility, and object recognition through electro-tactile stimulation to the tongue.

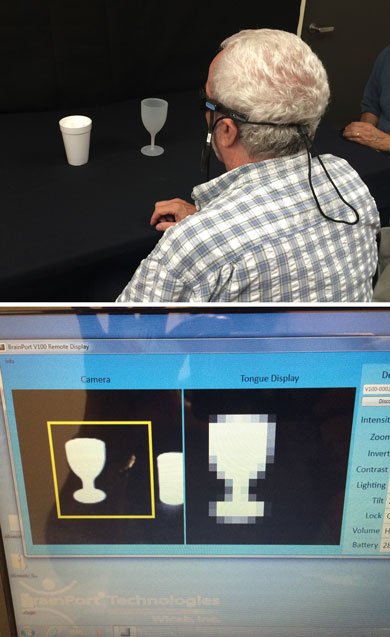

The device is composed of sunglasses with a built-in camera, an intra-oral device (which users have dubbed “the lollipop”), and a handheld remote that controls the level of electrode stimulation as well as contrast and zoom functions on the camera. The camera digitizes and translates the world around the user by passing electrical current through hundreds of tiny electrodes on the lollipop that trace translated patterns onto the user’s tongue.

White, light-colored, or bright areas picked up by the camera translate into strong stimulation in the corresponding electrode pattern on the lollipop. Dark or black areas create no stimulation, and gray levels register as medium levels of stimulation.

BrainPort V100 users report that it feels like pictures are being painted on their tongues with tiny bubbles. “It’s a vibration, just like how your phone vibrates, but very gentle,” says Patricia Grant, Wicab’s director of clinical research. Users “can increase or decrease the sensitivity, [and], depending on how close an object is, you’ll feel a larger portion of your tongue covered.”

The current and first model, the BrainPort V100, received approval for consumer use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in June 2015. Wicab sold its first unit the following September. Originally, the device cost $10,000 but has since dropped in price to $7,995. To date, Wicab has sold seventy BrainPort units.

While the device is, by all means, cutting-edge technology, it’s actually been in the works for almost twenty years. And the primary theory behind why the BrainPort works has been around even longer.

• • • • •

Dr. Paul Bach-y-Rita, a New York City-born medical doctor and pioneer in the fields of sensory substitution, rehabilitation medicine, and neuroplasticity, founded Wicab Inc. in 1998.

“He developed the idea of sensory substitution and brain plasticity—where the brain can evolve and adapt to its environment—back in the 1960s,” says Bill Conn, the company’s vice president of sales and marketing. Conn adds that Bach-y-Rita’s work is regarded as the first experimental evidence for brain plasticity and the pursuit of sensory substitution.

Bach-y-Rita first saw the brain’s amazing ability to adapt after his father Pedro, a poet and scholar, suffered a stroke. The stroke left Pedro paralyzed and unable to speak. Bach-y-Rita’s brother George, a psychiatrist, developed a routine of simple tasks—sweeping and scrubbing pots—for his father to do to aid in motor-skill re-training. With the help of George and the rest of the family, Bach-y-

Rita’s father eventually learned how to walk and talk again. Pedro’s recovery became even more remarkable when, after his death, an autopsy revealed that the stroke caused irreparable damage to a large portion of his brain stem.

This revelation was formative in Bach-y-Rita’s understanding of the brain’s amazing ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections. Bach-y-Rita began his life’s work while at the Smith-Kettlewell Institute of Visual Sciences in San Francisco and returned to his research in neuroplasticity in the 1990s as a professor of rehabilitation medicine and biomedical engineering at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Initially, Bach-y-Rita’s research led to the creation of a device that transmitted visual information from a camera to a blind individual through a vibrating plate worn on the back. But, in the late 1990s while at UW–Madison, Bach-y-Rita identified the tongue as an ideal interface to the brain not only because of its hypersensitivity but also because a moist environment enhances electrical conductivity. Early versions of the BrainPort were much larger than today’s, and the attached hardware required a cart. Over time, technological advances in both camera and computer miniaturization led to many—and smaller—redesigns, making the device much more portable.

Bach-y-Rita, who passed away in 2006, never got to see the current iteration of his lifelong research. The BrainPort name, however, makes more sense when you consider the inventor’s favorite saying: “You don’t ‘see’ with your eyes; you ‘see’ with your brain.”

• • • • •

Wicab’s main office and research facility is located in a neighborhood of modern-looking office buildings just outside of Middleton. It’s here that they host clinical trials for the BrainPort, providing subjects with up to ten hours of training.

Some user training includes things like item discrimination tests. For these, the user will be presented with a ball, a box and a banana and they must “reach out and grab the banana deliberately without tapping around the other objects,” says Aimee Arnoldussen, a consultant for Wicab who works as the technology assessment program manager for UW Health.

Research director Patricia Grant says that it is “really up to the individual how proficient they’ll become with it.” She compares it to learning a language, noting that, to become fluent “you have to work at it all the time.”

Grant notes that the device can be just as effective for those who are born blind as for those who have had sight for some portion of their life. “Everyone assigns their own definition of what things are,” she says. “So, whatever you perceive a banana to be is enough—whatever your own perception is, it’s enough to identify it again. We’ve proved that visual memory does not need to be there.”

Grant notes that the device can be just as effective for those who are born blind as for those who have had sight for some portion of their life. “Everyone assigns their own definition of what things are,” she says. “So, whatever you perceive a banana to be is enough—whatever your own perception is, it’s enough to identify it again. We’ve proved that visual memory does not need to be there.”

Grant and Arnoldussen both say that the learning curve for most new BrainPort users is relatively short.

“There’s definitely an a-ha! moment [and that happens] pretty fast. In the first hour, the person understands orientation—up, down, left, right,” says Arnoldussen. “What we found was that the more fun the person is having, the quicker they are to learn, and that will help them do more and ever-challenging things.”

According to Arnoldussen, some users are trained and tested on how to “navigate hallways, be aware of turns, or follow a path that we had mapped with masking tape on the floor.” At one point she even made a maze of sorts. “I hung tires from the ceiling that people could try to throw things through or avoid as an obstacle [to understand] how people could do these novel tasks that they couldn’t do with a cane or a guide dog.”

It is the stories of the BrainPort’s use in the field, especially in situations that they could never test in the lab, that stick with Grant and Arnoldussen.

“I took someone out on a BrainPort sightseeing tour in Chicago, and this person was able to see a waterfall and describe to me the pattern of the water,” says Grant, adding that she heard some users even watched last summer’s lunar eclipse using the BrainPort.

Arnoldussen says that one of her favorite descriptions of the BrainPort experience comes from a user who likened it to sitting in the back of a car. “You’re not driving and you’re not paying attention to everything, but you’re seeing things that are out there and you’re aware of it,” Arnoldussen explains. “She didn’t have to know what everything was, but it gave her context and [told her] where she should direct her attention.”

• • • • •

Since the BrainPort V100 received U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, Wicab has been focused on getting it into the hands—and onto the tongues—of more users.

While there is currently no competition for similar devices on the market, vice president of sales and marketing Bill Conn notes that the cost of the device is a significant barrier for people. “Our market, which is profoundly blind people, for the most part, don’t have a lot of money, or they tend not to be working, or are a small part of the labor force,” says Conn, adding that the company is undergoing a “big push” to get the product approved by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies.

Over the years, Wicab has relied on a variety of funding sources for research and development, including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Google, the Pennsylvania Office of Research, the National Science Foundation, and Angel Investors, among others. The U.S. Department of Defense recently funded a trial to evaluate the effectiveness of the BrainPort in a discrete traumatic brain injury population: Armed Forces combat veterans. In addition to the DOD trial, Conn says that the U.S. Veterans Administration also has begun purchasing BrainPorts.

People and organizations alike are beginning to learn about the efficacy of the BrainPort, just as Wicab is also set to release a new version of the device in early 2018: the BrainPort Vision Pro. Instead of utilizing sunglasses, the device is “a headset-style product [with] user controls built into the headset itself. Users can put it on and take it off very quickly,” says Conn. Wicab engineers are also investigating smartphone apps for the vision device, specifically one for reading everyday signs such as those for stairwells and restrooms.

Grant notes that there is unlimited potential for this technology to grow. “Think about driverless cars,” she says. “That is what we want the BrainPort to be. If a car can drive itself, a person can navigate down the street by using the BrainPort V100.”

The Wicab team is even reviving another of Bach-y-Rita’s earlier ideas, the BrainPort Balance Plus, which also uses the lollipop interface to help people suffering from balance issues caused by stroke, Parkinson’s disease, or vestibular disorders.

“It’s an electronic-training aid that provides real time feedback about the user’s head and body movement when they’re doing balance training exercises,” explains Conn. “When they’re leaning to one side or the other, they may not realize it. This product will prompt them to bring their head back to the center.”

All of these new technological advancements capitalize on the brain’s amazing ability to reorganize itself and help patients to help themselves. Andy Fabino sums up the transformative power of Wicab’s BrainPort: “It does not replace the cane, it does not replace vision. [But] it aids in the everyday living,” he says. “I feel confident now. Empowering is not a strong enough word. This provides a little bit of light in an otherwise really dark place.”