It’s been three decades since I took my first bite of wild game. It was the fall of 1992, and, fresh out of graduate school, I had just begun my first real job—production manager for scholarly journals at the University of Wisconsin Press. At lunch time one day, my size 13 Doc Martens clambered down the oak stair treads. The Journals Division was one of three Craftsman style houses that—along with a warehouse once belonging to the defunct Fauerbach Brewery and still smelling of must and grain—made up the Press’s quarters at the time. Opening the refrigerator and realizing my leftover pot roast was at home, I was hit by a blend of low blood sugar and sadness.

The one block to Fraboni’s Deli—with its spicy olives and cured meats—felt miles away and, anyway, I didn’t have money for a sandwich. I stared out the window at the leaden sky and the railroad tracks beyond the Press buildings. Just then, I heard the ding of the microwave door. A commingling of meat and citrus filled the air. My supervisor and Journals Manager, Steve Miller, divided the contents of the Tupperware he’d heated onto two plates and slid one down the counter to me. I grabbed hold of a bird leg cased in crisp brown skin and flecked with sauerkraut. Dark, tender meat fell from the bone. The taste stirred something primal in me. It was at once rich and lean, steak and poultry—unlike anything I’d eaten and magically satisfying. I asked the bluntest and—it would turn out—most transformative question I could muster: What is this and how do I get more?

Rathskellers and Smoking Barrels

Steve told me the meat was wild duck that he’d shot on the Mississippi River the previous weekend. Moreover, he invited me hunting and we were often joined by his friend and Associate Press Director, the late Ezra “Sam” Diman. My interest caught like brushfire, and the two of them were just the kind of mentors a young hunter needs—wool-clad and dependable, tempered by a gallows humor that salved the sting of shots and outings gone awry. We hunted far and near. The Lucey Farm and the overgrown right-of-way behind the School for Girls. French’s Creek and Grand River and Hog Island. Rugby and Aberdeen, Jamestown and Gackle. There were mustard yellow duck skiffs and decoys made from cork salvaged from a refrigeration plant. Dusty rathskellers turning out great racks of pork ribs atop crispy potatoes. There was the smell of cordite, sharp in the cold air, as we crouched between prairie potholes, the barrels of our Wingmasters smoking, the sun bleeding out into the Western sky.

Sam and Steve gave me heaps of encouragement and guidance as I learned to hunt: first squirrels and rabbits, then birds, and ultimately deer. They were the “social support” one hears about in outdoor skills research. Their steadfast company notwithstanding, they were not, per se, the reason I decided to try and—ultimately to embrace—hunting. This was something I’d uncovered, as one might find an ancestral portrait or coat of arms deep within a fieldstone basement. This inner wildness was about pursuing—and eating—wild game. Or, more accurately, connecting with something that had long been part of human existence and only recently had faded from view. As I progressed as a hunter, I also grew as a chef, beginning with simple sears over glowing coals and black skillets and then progressing to savory stews like Squirrel Burgoo or Rabbit Cacciatore and sharing them with loved ones. While I vaguely sensed that I was on a path, I would never have guessed that, decades later, its arc would have been so profound and circular.

With my first steady paychecks, I began to acquire the material trappings one needs to become a hunter. I bought a used Remington Wingmaster, a few burlap sacks of decoys, a Karsten’s duck skiff. My wife Kerry and I used the money we received from our wedding as a downpayment for a cabin on the banks of the Kickapoo River. I hunted feverishly into my 30s, accompanied by a lithe black Labrador retriever named Tasha, and worked at various editorial jobs. The more game I ate, the more I wanted to learn about cooking it. Books from LL Bean, Remington Arms, Ducks Unlimited—as well as spiral bound cast-offs and jottings on scrap paper—were my bedtime reading. In my 40s, narrowing the gap between my personal and professional worlds, I became a full-time freelance outdoor writer. Scores of articles in the conservation press and then publication of Driftless Stories and Fly Fishers Guide to Wisconsin and Iowa followed. Then came invitations to run game cooking seminars at the Journal-Sentinel Sports Show, the Wisconsin Writers Festival, and DNR facilities. By 2008, I had collected enough recipes to pen my first cookbook, Wisconsin Wildfoods. Wild Rice Goose and Other Dishes of the Upper Midwest followed in 2013.

In 2014, I took the position of Shooting Sports Assistant at the Wisconsin DNR. A central job duty was helping to design and implement a course called “Learn to Hunt for Food,” a brainchild of then Hunting and Shooting Sports Program Specialist Keith Warnke. The goal here was to reproduce for novices just the kind of experience—and support—that I had gotten. Following five years of work at WDNR, I’ve been fortunate enough to continue this rewarding career on the nonprofit side as the Wisconsin Recruitment, Retention, and Reactivation (R3) Coordinator for the National Wild Turkey Federation (from 2017 to 2022) and since then as the Wisconsin R3 and Outreach Coordinator for Pheasants Forever.

Diving Into Demographics

Hunt for Food classes (WDNR adopted the term Learn to Hunt for these classes in 2023) didn’t just happen. This, like all stories, is backed by other stories. To begin this one, hunting license sales in the United States and Wisconsin peaked in the 1980s and 1990s. Since that time, the demographic “bubble” representing Baby Boomers (those born between 1948 and 1964) continues to advance across the age spectrum. In fact, the average age is closing in on 70, which is when most people stop hunting. Of course, one can point to many Baby Boomers who do hunt—and avidly—but those cases tend to prove the general rule that this age cohort is becoming and ultimately will be too old to engage in the tasks associated with hunting: climbing tree stands, dragging deer from the woods, following bird dogs over rough terrain.

This is important because conservation funding comes from hunting licenses sold, and even more comes from the 11 percent Pittman-Robertson federal tax placed on firearms and ammunition. In other words, declining hunter numbers spell serious economic and relevance problems for the conservation community. Historically, creating new hunters to backfill those who aged out has taken care of itself. A high density of hunters, who in turn taught their children to hunt, kept the pool of license buyers robust. But as America has grown more urban, as average family size decreases, and as more pastimes (like digital media and team sports) compete for the family calendar, fewer hunters are being produced. This decrease is expected to become more pronounced as the Baby Boomer cohort continues to age.

At the same time—and this can perhaps be viewed as a happy coincidence—Americans in general and millennials in particular are becoming increasingly concerned about their food sources and food sovereignty—for meat in particular. It’s not difficult to see how a ready-made sales pitch (secure your own ethically sourced meat through hunting) and an audience (millennials and others who eat meat but dislike factory farming) seem to suggest themselves. This line of thinking wasn’t lost on natural resources professionals like Warnke, who pioneered the first WDNR Hunt for Food class in 2012.

Warnke, who is now the Midwest R3 and Relevance Coordinator, put it this way: “This strong interest in food sources easily carries over to hunting. Killing meat themselves from a wild, sustainable resource is very attractive. It builds on their values of conservation, land ethic, and animal use.”

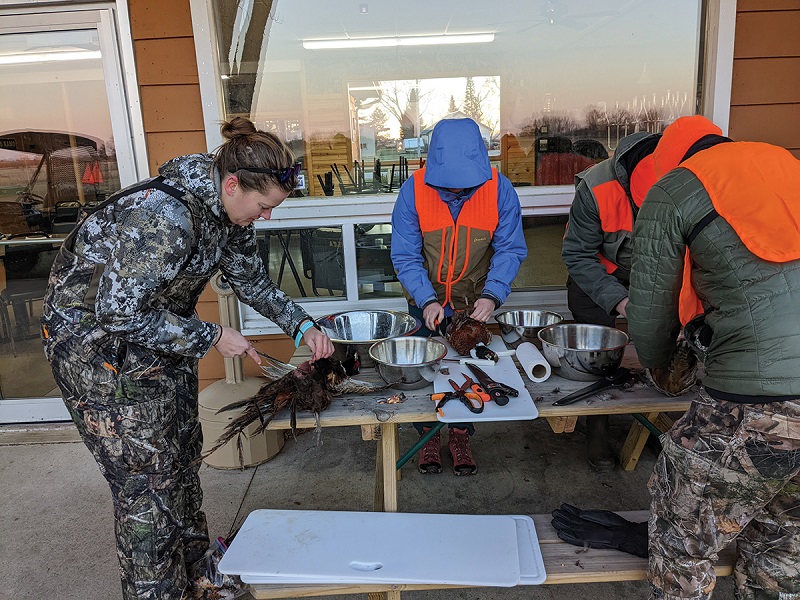

Not surprisingly, given the urban and suburban demographic of Hunt for Food participants and the students’ lack of exposure to firearms and animal processing, Hunt for Food classes are long courses rather than short ones. The many skills necessary to hunt—marksmanship and gun safety, field dressing and butchering, basic biology and regulations—are taught over something like 10 hours in the classroom and field. To get a sense of the class experience, readers can google the term “Hipster Hunter.” Alternatively, a literature search will reveal a wide range of publications covering similar stories over the last five years. A short list includes the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, National Public Radio, Slate.com, Outdoor Life, Field Stream, and MacLeans.

Just as WDNR was among the first state agencies to offer courses like Hunt for Food, it now continues to lead the way in the realm of R3. As of fall 2023, four distinct conservation organizations have partnered with WDNR to create partner R3 coordinators: Pheasants Forever, the National Deer Association, Raised at Full Draw, and Pass It On Outdoors. While these nonprofits each have their own point of view, all four partner R3 coordinators share the aim of creating new hunters and are financed through Pittman-Robertson revenues.

According to WDNR R3 Supervisor Bob Nack, “Wisconsin DNR was one of the early leaders in recognizing the importance of outdoor experiences that occur when hunting, fishing, and trapping. We are excited to continue as a national leader in providing programs.”

Students Speak

Because I was so affected by hunting, I have been keenly interested in how it affects others. Statistics are one way to prove a point, and one study of Hunt for Food students in Wisconsin shows that 40 percent of them became regular license-buying hunters. My own records suggest that this number may be closer to 50 percent. Further, all students were shown to hold a favorable view of hunting after completing Hunt for Food classes. These statistics may seem underwhelming and self-validating. If only half the students in a course on basket weaving go on to weave baskets, wouldn’t we question the worth of that class? And, if someone is considering taking a class, doesn’t this imply approval?

Considering the degree of behavioral change involved in going from being a nonhunter (someone who does not take the life of animals for food) to becoming a hunter (someone who takes the life of animals for sustenance within a strict code of regulations), one realizes that the bar is very high here. In fact, it is difficult to envision a change that is weightier than taking the life of another being. That said, if roughly half the sample set chose to undergo this change, the agent of change—Hunt for Food classes—can be viewed as a powerful catalyst. That students enroll in courses on which their point of view is already established tends to put the cart before the horse. While one can certainly take a course on a subject in which he or she is already interested and disposed to view positively. Just as often, one can enroll in a course about which he or she is undecided, ambivalent, or just plain curious. So, unless all students were unanimously positive about hunting prior to enrolling in Hunt for Food, it’s fair to say at least some underwent a change of opinion. Bolstering this are my observations as an instructor with more than a decade of teaching such classes: I’ve observed most entering students exhibit some degree of fear about using a firearm and taking an animal life. A unanimously positive subsequent view of hunting here suggests that this fear is allayed or overcome.

According to the current WDNR Hunting and Shooting Sports Program Specialist Emily Iehl, whose master’s thesis is cited above, “There appears to be lots of interest in Hunt for Food among people who didn’t grow up hunting. If we can offer relatable resources, experiences, and instructors, people are likely to take advantage of this.”

A brief scan of comments from Hunt for Food students shows similar sentiments. One student says, “I took a series of these classes, and now hunting and fishing for my own protein are an integral part of my life.” Another adds, “Without this class, I would not have felt prepared to join a group of seasoned hunters. The programs were a gift to help me carve out time for being outdoors, learning new skills, and navigating the ethics and emotions of hunting with a friendly and welcoming group.”

Still another says, “My family gathered and we feasted upon the wild turkey meat. As we digested, we could feel the meat nourishing our bodies and spirits, slowly becoming and building our life-filled molecules. The impact of this turkey hunt and the subsequent memories and nourishment it provided are simply intangible. Hunting and eating locally is a way of life that is as natural as the seasons.” Finally, another expressed that “these programs were my guide into the unknown ... without them, I’m certain this would still be a distant dream.”

Deep Bonds and Walking Shadows

Novice or veteran, mentor or mentee, we live lives that are brief and bound by work and family. And yet, in this sojourn we undertake without mile markers, in this theater where we’re given no playbills, we find ourselves connected to others. We share a common experience. As I had the good fortune to learn, I am compelled to teach. The people I’ve met through hunting—male and female, gay and straight, Black, brown, and white—have become an extended family. We’ve logged in what feels like a lifetime on duck marshes and uplands, trout streams and lakes, backyard barbeques and game dinners. A particular day in the grouse woods with one friend comes to mind. We decided to take a break from hunting in a field of blackberry and milkweed. We picked up the milkweed pods, and, whimsically, let the floss fly out into the autumn breeze, watching it slip away toward the Minnesota line and then finally fade into nothing. We laughed together, and then laughed some more. In addition to the humor, I also felt something else which I can only put into words after the fact. No matter how hard we strive, no matter how much we want to pass something along, we’re still just small specks in a vast and existential enormity. “Out, out, brief candle,” Shakespeare’s Macbeth tells us. “Life is but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more.”

Pheasant with Dried Apricots

This recipe is adapted from the cookbook Wild Rice Goose and Other Dishes of the Upper Midwest by John Motoviloff. It is a

low-and-slow dish that gives a nod to ingredients such as dried fruit and cinnamon that evoke Central Asia, where pheasants originated.

Ingredients

2 Pheasants, cut into serving pieces and seasoned with salt and pepper (or equivalent weight in thighs and drumsticks)

Flour for dredging

¼ C olive oil plus 2 Tbsp butter (more as needed)

2 C chicken or pheasant stock, heated to just

below boiling.

I C dried apricots

1 C yellow raisins

1 cinnamon stick

3 Tbsp honey, or more to taste

Additional salt and pepper to taste

Cornstarch for thickening if needed

Preheat oven to 275 degrees. Place shallow baking pan in

the oven.

Dredge pheasant pieces in flour and shake off excess.

Heat a large Dutch oven, Le Creuset, or similar lidded, oven-proof vessel on the stovetop. Add oil and butter and heat until it sizzles. Brown pheasant pieces in batches, being careful not to crowd the pan. Place browned pieces in the baking pan as you work.

When all pieces are browned, scrape up any remaining bits with a spatula or wooden spoon. Deglaze the pan with stock. Replace the pheasant pieces. Add the dried fruit plus the cinnamon stick and honey.

Bake, covered, until pheasant is fall-off-the bone tender. Taste the liquid to see if it needs more salt, pepper, or honey. If the sauce is too thick, add broth or water. If it is too thin, add cornstarch dissolved into a few tablespoons water.

Serve over saffron rice.

Duck à l’Orange

There are many versions of this classic dish, and it’s served in both high-end restaurants and at the homes of humble duck hunters. The sharp taste of citrus contrasts nicely with the rich and meaty fowl, making it a winning combination. Take care not to overcook wild duck, as it becomes livery and tough. Interestingly, the author’s first bite of wild game was a version of Duck a l’Orange complimented with sauerkraut and caraway seeds.

Ingredients

Breast fillets of prime-quality ducks (such as mallard, wood duck, pintail with skin left on). Substitute domestic duck breast, which will require slightly longer cooking, if wild duck isn’t available.

Salt and pepper

Flour

4 Tbsp clarified butter (butter with dairy solids removed)

1 C sherry or port

2 oz currant jelly

1 Tbsp grated orange rind

1 tsp of fresh grated ginger

1 C fresh squeezed orange juice

Water or broth as needed

1 Tbsp sugar (more as needed)

1 Tbsp cornstarch dissolved in a bit of cold water

Preheat oven to 200 degrees.

Salt and pepper duck breasts. Dredge them in flour and shake off the excess.

Heat a large cast iron or nonstick skillet on the stovetop. Add butter.

Brown each breast fillet well on either side. Do not cook the duck fully at this point; it should still be cool and pink at the center. Remove to oven.

Deglaze the pan with sherry. Add the currant jelly, orange rind, ginger, and orange juice. Simmer and reduce to half the original volume.

If too little liquid remains, add broth or water. Stir in the corn starch-water mixture. Taste the sauce. If it seems right to you, leave as is. IF you find it too tart, add sugar a little bit at a time. Check for salt and pepper and add as desired.

Replace the duck breast in the sauce, making sure to coat on both sides. Cook until just-done. Serve on the side of wild rice or mashed potatoes. A robust Côtes du Rhône or Bordeaux will round out the meal.