As kingfishers catch fire, dragonflies draw flame …

Crying What I do is me: for that I came.

—Gerard Manley Hopkins, “As Kingfishers Catch Fire”

The news came just as I was about to walk into a classroom full of students. An emergency room doctor explained in a calm voice that my father had fallen and broken his jaw. He was conscious and talking, but they were concerned because a CT scan had shown evidence of bleeding in his brain. They didn’t know how bad it was, but they would be rushing him to the UW Hospital in Madison. There, he would be seen by specialists. I steadied my voice and asked the doctor if I could speak to him.

My father’s voice when he spoke was a tightrope stretched between two trees. “I tripped taking out the trash. My brain is bleeding, Heath,” he said over the phone. And then his voice faltered, and he forced out, “I love you.” I choked out an echo. An awareness that I might not see him again sent a chill through my body, like stepping out of a house into the February air with no coat.

In the momentary silence that followed, I remembered something from when I was in labor with my first child. After more than 24 hours at the hospital, I was not progressing. Then, for a variety of reasons, all my vitals dropped: they were losing both me and the baby. I was rushed down a hallway toward an emergency Cesarean-section. I remember my only hope was that they could save my child. Just before we passed through the metal doors to the operating room, I saw my dad’s face above me, his eyes clear and direct. He could see I had given up. “I’ll see you in twenty minutes,” he said firmly, like a command.

There, in the hallway of the school, holding on to the wall to keep my balance, my voice rose into my throat as I said into the phone, “I’ll see you when you get to Madison.”

• • • • •

I recall my early childhood as one filled with nature and art. Both of my parents were artists—my father, a painter, and my mother, a potter. My family gardened and raised chickens on a little plot of land in in the middle of the woods near a prairie, far from any important museums. We often visited local galleries and openings, the studios of other artists. Most evenings we played music, told stories, or read the poetry and art books that lined our shelves.

I grew up knowing artists the way some people grow up knowing baseball players; I recognized their signatures of style, subject, and line. I could identify works by Western masters like Da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Michelangelo, but also those by Van Gogh, Monet, Albright, and others who explored the way paint could be applied. Those who broke with tradition in subject matter and form like Cézanne, O’Keefe, and Hopper were just as familiar to me as painters who had moved past representation: Rauschenberg, Pollack, and Stella. I don’t remember my parents ever asking me to memorize these things.

When I was six years old, we visited the Art Institute of Chicago, and I was able to view these familiar paintings in real life. All of a sudden I could see the dimensionality of the paint, the actual sizes of the pieces, feel the emotion in the sweep of the brushstrokes. Chagall’s stained-glass America Windows especially captivated me: the colorful floating animals and people seemed more real to my young mind than the careful urban renderings of the Ashcan School or the life-like portraits of Rembrandt.

I never thought to share my knowledge of art with anyone. None of my friends talked about art, and the subject rarely came up at school beyond the simple drawings or paintings we were asked to make in class. But, because of my parents, I knew art was important. It did things, said things that other kinds of activities simply could not.

• • • • •

When I arrived in the ER at the UW Hospital, I found my dad in a neck brace that dwarfed his small body. There was still blood on his unshaven jaw, and he was covered with electrodes hooked to machines. I held my hand on his forehead, where his skin seemed unusually fragile and thin. We are not hand-holders. Our hugs are a quick squeeze at the end of a visit. But I kept my hand there on his head, hoping to somehow hold his fierce spirit inside him.

Trauma doctors, neurologists, bone specialists, various residents and RNs visited my dad, each with a different task. Thankfully, the bleeding in his brain had subsided. He seemed not to have any neurological damage. But he needed to undergo a surgical procedure that would require wiring his jaw shut for three to four weeks. This concerned the doctors because he was already thin, somewhere between 95 and 100 pounds, and he would need a liquid diet. Another complicating factor in his recovery would be his Parkinson’s disease, which at this stage had begun to affect his ability to get around, to care for himself. The disease, they said, likely contributed to his fall.

• • • • •

A disease of the central nervous system, Parkinson’s in its early stages causes involuntary muscle movements. It affects fine motor skills, walking, balance, and, eventually, swallowing and speaking. Facial expressions are slowly diminished. For those who have it, the aperture of physicality slowly and steadily closes over time, shrinking one’s engagement with the material world.

In an interview with Jane Pauley, the actor Michael J. Fox discussed his personal experience with Parkinson’s disease. Fox was considering the twenty-year journey that led him to establish the Michael J. Fox Foundation to raise funds for a cure for Parkinson’s. Pauley had asked Fox how it felt to get the diagnosis, to hear words like degenerative, progressive, and no cure. “All that stuff is now irrelevant to me,” Fox had said. “I am not about measuring how long something will last or how long I can do this. It’s pointless. It’s just another thing that you face and you carry on.”

• • • • •

As my father underwent surgery, I waited in the hospital with hundreds of other people seated in uncomfortable chairs in strangely lit rooms with televisions droning on about new cars, weight loss products, or the stock market. Some researched diseases on their phones, some tried to make small talk, some sat by bedsides, silently praying.

The anesthesiologist saw me sitting outside the surgical suite when the surgery was over. He looked at me, making an assessment, and said, “You seem like a quiet person.” I followed him to the post-op room and sat down next to my dad. The room was dim, and I could just make out my dad’s name on the plastic band that hung from his thin wrist: Keith Davis. While I waited for him to wake up, I watched the machines all around him. It seemed so appropriate somehow that his life was being represented in colored lines: red representing his heart, green representing his breath.

He finally forced his way through the spiderwebs of anesthesia, exhaling in moans as he awoke. I spoke to him quietly. Hi, Dad. I’m here. You’re okay. You made it. When he opened his eyes and saw me, he lifted one hand and pantomimed writing. I pulled an envelope and pen out of my bag and placed them in his hand. Writing was always a slow and mindful task since Parkinson’s had set in. With more than the usual painstaking care, he wrote in shaky script: Sing the lullaby.

The lullaby was a wordless Native American song a friend had taught me that felt to me a bit like prayer. I sang it to my daughter every night. Once when my father was visiting, he heard me sing it and then asked me to sing it into his answering machine. He thought it was beautiful, not my singing, really, but the earnestness and simplicity of the song. What he wanted after the ordeal was not pain medication, but music. When I began to sing, very quietly, there in the sterile post-op room, amid all of the medical staff, his face contorted and tears streamed out of his eyes.

Thank you everyone, was the second thing he wrote.

• • • • •

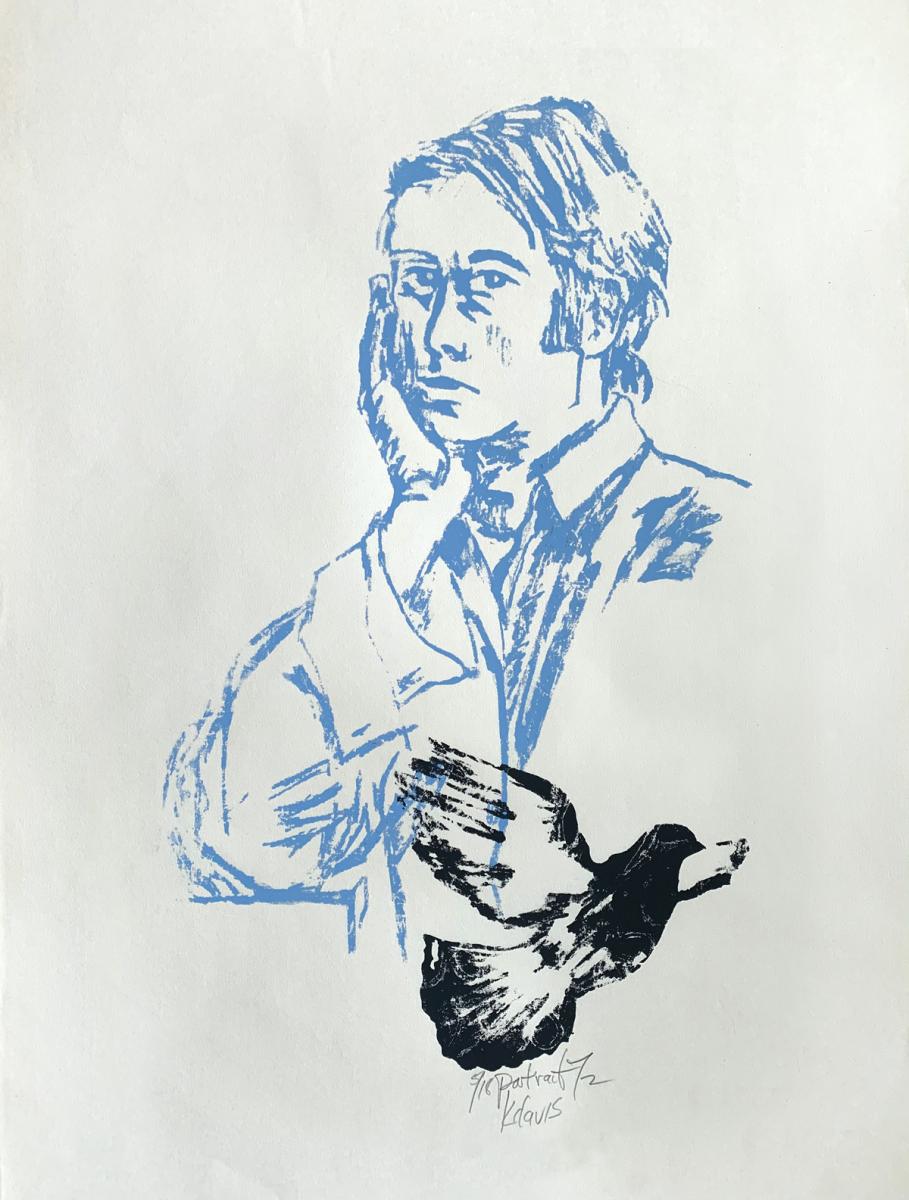

My father painted under the name Arthur Kdav. His earliest works show evidence of his exploration of color and line, the possibilities of paint and form. In his hands, familiar things—coffee pot, stream, rocking chair, or tree—seemed to reveal their essence, something like what I imagine the Victorian poet Gerard Manley Hopkins would have called inscape. My father painted with broad brush strokes that provide just enough visual information to let the viewer know what the subject was, leaving the rest to imagination. In this way he painted not so much the thing, but the spirit of the thing. The planes of color in the spaces around these familiar things hinted at his movement towards abstraction.

While he felt a great affinity for the German expressionists, in his opinion the abstract expressionists better challenged his thinking about the limits of representation, and his paintings continuously danced between visual narrative and the pure experience of color. He always said he admired Rothko’s ability to invite the viewer into an emotional state merely with patches of color.

My father’s intent was to paint the blind spots, the things we as humans might not usually think about or articulate, the things that remain a mystery. By the time I was old enough to really consider what he was doing, even the recognizable images in his paintings had become cloaked in symbolism. He then began welding together steel bar structures that looked like undulating plants or wings or waves over which he stretched canvas. He said he no longer wanted to be confined to a picture frame.

• • • • •

The bed and the chair in dad’s hospital room had sensors that alerted the nurse’s station when he stood up. He was a “fall risk” and needed to have a medically trained person in attendance when he got up for any reason, whether to stretch or go to the bathroom.

My father values privacy more than most people I know. We often mention something a friend’s mother once said about our family: They are so private that they probably change their minds behind closed doors.

My dad didn’t tell anyone when he noticed the first signs of his disease. The Parkinson’s first crept into his right arm, which occasionally “acted dumb” he later said, not doing what he asked. At the time, he was living alone in a studio he had built in a wooded area surrounded by farms in Iowa County. There was no running water, so every day he carried a bucket to and from a spring half a mile away. He slept on a mattress on a large wooden platform he’d built and spent most of his time painting in the main room, which had two glass-door walls that flooded the space with forest-filtered light. It was beautiful, but very isolated. After his Massey-Ferguson tractor lost its brakes, and he rolled backwards down a hill and into a tree, I began to encourage him to move to Mineral Point, which eventually he did.

When the disease truly began to affect my father’s hands, he gave up welding and returned to two-dimensional painting. When the state prohibited him from driving, he bought a three-wheel bicycle with a large basket for runs to the store. When a fork required too much precision, he began using a soup spoon. When he had trouble mixing paints, he took up painting on paper with paint markers. When his voice gave out, he sang songs during the day to keep his vocal cords loose.

Certain things surprised him, though. He called me one morning to celebrate the fact that he could still crack an egg. When he visited my house, he would occasionally plunk out notes on my piano, one finger at a time, of pieces he’d written when he had control over his hands.

• • • • •

My paternal grandfather was born and raised in India. He was sent to the U.S. to attend a Christian college when he was eighteen years old. He stayed here, got a job and a house, met a girl and got married. He carved and polished gem stones in his basement, attended meetings of a “spiritual society” to which he wore a turban, sang to my father songs he knew in Telugu. He was dedicated to my father and my grandmother, who was Episcopalian and had grown up in a family of nine children. Her mother had died when she was quite young, and poverty plagued what was left of her childhood. She told my young father stories of gathering coal by the railroad track, of often going to bed hungry. Despite her difficult childhood, she educated herself and eventually landed a job working for a lawyer. My grandparents had only one child.

My father’s creativity led him to breaking rules early in life. At age ten, he and a friend rigged up a homemade telegraph system by stringing wires between their two houses, using city electrical lines for scaffolding. The city immediately shut down this system (clearly a fire hazard) when they got wind of it. At twelve, he and another friend built a raft out of an oil drum, old tires, and wood scraps and launched it in a pond in a local park. A passing policeman seized the boat and lectured them about trespassing.

By college age, he became interested in understanding the mysteries of the universe. So he took classes in physics and in art, eventually poring himself into painting and printmaking. And he read lots of Thoreau, especially Walden:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.

The day after my father graduated from Knox College in central Illinois, he packed everything he needed into his car—mostly paints and his dog-eared copies of Walden and Leaves of Grass—and set off on a pilgrimage to Walden Pond. His arrival at Thoreau’s former home just outside of Concord, Massachusetts, was less than wonderful. It was not the pristine wild space my father had dreamed about. There was a snack shack where you could buy hot dogs and souvenirs; signs and tourists were everywhere.

At the gift shop, he told the shopkeeper that he had come to the East Coast to make his living as a painter. The shopkeeper told him to go to Marblehead. There were painters there. Good ones. And for some reason, perhaps fate, my father took the advice. He moved to Marblehead, rented a shack to use as a studio, and began making sails for a sailboat maker. After a few months in Marblehead, introducing himself to artists, painting, and learning to sail, he met my aunt. One afternoon, while visiting my aunt at my grandmother’s house, he heard my grandmother read a letter from my mother, whose prose described in great detail her experience of jumping out of an airplane in Colorado. As the story goes, my father fell in love with her then. Within a year they were married.

Years ago, I visited Walden Pond on a whim. I took off my shoes, rolled up my pant legs, and stepped into the shallow water. I had not come expecting any moment of enlightenment, but suddenly a profound gratitude overtook me. This water, this place had inspired Thoreau to write the words that would cause my father to leave his family behind and come here, determined to “live deep and suck out the marrow of life.” Had Thoreau not written those words, I never would have been born.

• • • • •

In a way, my father lived out Thoreau’s manifesto more fully than did Thoreau himself (who, after all, had family nearby to help him out). When my mother and father married, they bought a cheap parcel of land in the country and slowly built their house. They grew their own vegetables, hauled water from a well, and cut wood to heat the house in the winter. My father built a kiln for my mother, and the two made art and music, and had children whom they intended to raise free from the trappings of materialism and the influence of television. For a time, it worked well, until my father felt he needed to explore another path. My parents were married for seven years.

At the height of his art career, companies, organizations, and homeowners from all over the country paid him to design and compose massive sculptural paintings for their spaces. One painting, made for a building on the UW–Whitewater campus, is 27-feet long. Another, designed for the Maricopa County Building in Arizona, wraps around a corner of the second story balcony above the main entrance. During this time, he also produced smaller pieces that found their way into galleries across Wisconsin, and his work was represented by galleries in Chicago, Sarasota, Atlanta, and St. Louis.

In between his work on commissions, travel, and personal projects, my father also purchased and renovated a number of buildings, all while being a father to his two younger daughters and a husband to his second wife. This marriage did not last, either.

Once, glancing through one of my father’s books called Letters on Cézanne by Rainer Maria Rilke, I noticed he had underlined a sentence: “It seems to me that ‘the ultimate intuitions and insights’ will only approach one who lives in his work and remains there.”

• • • • •

Before the surgery, a doctor had come in to ask my dad a few questions:

If you go into cardiac arrest, do you want to be resuscitated?

“Yes.”

If you need a feeding tube, would you want it?

“Yes.”

Can you remember the words we told you to remember?

“Apple, penny, table.”

As the doctor scribbled his notes on the chart, I asked the nurse about what comes after the surgery. She said that my dad would be free to go home after a couple of days, that there is no law in our state that requires him to remain in the hospital or a nursing home unless he is seen as mentally unfit to live alone.

I later mentioned this conversation to my dad, whose memory is often better than mine. He confessed that when he was coming out of the anesthesia, and I was not in the room, he thought he had been captured by some kind of cult and that the nurses were planning to drug him. I looked hard at him.

“Apple, penny, table,” he said to me with steady eyes.

Over the several days dad recuperated in the hospital, I struggled to keep my mind sharp. I needed to understand all of the information that the doctors were telling me so I could make good decisions about his care. Also, as the oldest, I had to report back to my three sisters what was happening.

The nurses would come and go, asking me questions.

So, he lives alone?

“Yes.”

Does he have any stairs in his home?

“Yes.”

Does he have trouble keeping on weight?

“Yes”

I didn’t understand why they kept asking me the same questions until one nurse said to me gently, but bluntly: The doctors are recommending that he not go home immediately and that he probably should not continue to live alone. He is at risk for another fall. Care facilities are available in the area.

I knew dad really wanted to go home, to his studio. I also knew that my dad knew he really needed the kind of physical therapy and nutrition regimen that could only be found at a rehabilitation center. Eventually, he agreed to go. But for no longer than a week, he insisted.

• • • • •

During one of the harshest winters in my memory, I brought my friend Samar with me to visit my father at his studio in Mineral Point. We all had experienced the weight of the winter, the short days and bitter wind scouring away our sanity. When Samar and I stepped into the gallery portion of his place, we stood spellbound. My father had painted at least ten tall pieces that radiated so much joy, with colors we had nearly forgotten existed. There he was suffering with his disease, alone, during that horribly cold winter, and what he painted was lightness and hope. My dad told us he painted what he didn’t have in his life.

• • • • •

The little community of medical professionals that formed around my dad wanted him to be safe. There were many discussions about quality of life. The nurses at the rehab center scolded him for walking with a friend—that is, without a trained medical person—to the large bird cage full of canaries down the hall from his room.

There was a print of a pastel drawing hanging in the room where they sent my dad for rehab. It was small, maybe 12-by-18 inches. The clearly competent artist had used an impressionist method to create a picnic table in dappled sunlight. Tiny scribbles of deep-yellow pastel spoke of late afternoon; the deep greens of the branches above the blue-white table cloth transported me to the hazy shade of summer days. I pointed at it, knowing my father had been looking at it for several days. “It’s nice to think about summer and being outside,” I said.

“Being here is like being in jail,” he replied.

• • • • •

Five days after they took him to the rehab center, my sister the librarian picked him up, stopped at a store to buy a blender, and took him home. She left him with a clean kitchen and stacks of Tupperware full of soup she had made. My sister from California sent him cases of Boost and new bedding. My sister the school teacher came the following week and helped him set up his computer downstairs so we could continue to exchange e-mails without his having to climb to the second floor.

Matisse was well known for his relentless work ethic. “Work,” he would say, “cures everything.” For my father, too, having a meaningful life meant working, making, doing. All winter he built fires in his wood stove to keep his studio warm. He cooked all of his simple meals, took his trash to the curb, shoveled his walk when it snowed. He read books about art, made charcoal drawings in the hours when he had the most control over his hands. Soon the weather would allow him to walk outside amidst the hollyhocks, day lilies, and plum trees that filled his small garden. He could still live deliberately, even with all of his limitations.

Of course, not everyone can make the choice not to live in a nursing home. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, there are roughly 1.3 million elderly people living in nursing care facilities in the United States. Some like the sense of community and safety these places can provide. Some have memory issues and require constant observation. Some are very sick and need continuous care.

But my father still has the choice, and he has chosen the risk of independence. There is no way to know what challenges his future holds. There are dangers of course, unknowns. But he is willing to live into the blind spots.

“What I do is me: for that I came,” wrote the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins.

• • • • •

After visiting my dad at his quiet studio in Mineral Point, I say goodbye and hug him. I know another accident could happen. There is no certainty, ever. I look back at him before getting into my car. He stands in the doorway, his body like a Giacometti, long-limbed with penetrating eyes, leaning at a precarious angle. Then he reaches up with one hand, fingers spread wide in a jubilant wave, joy emanating from every cell.

On August 27, 2020, Keith Davis died after a fall in his studio. He painted until his final days.