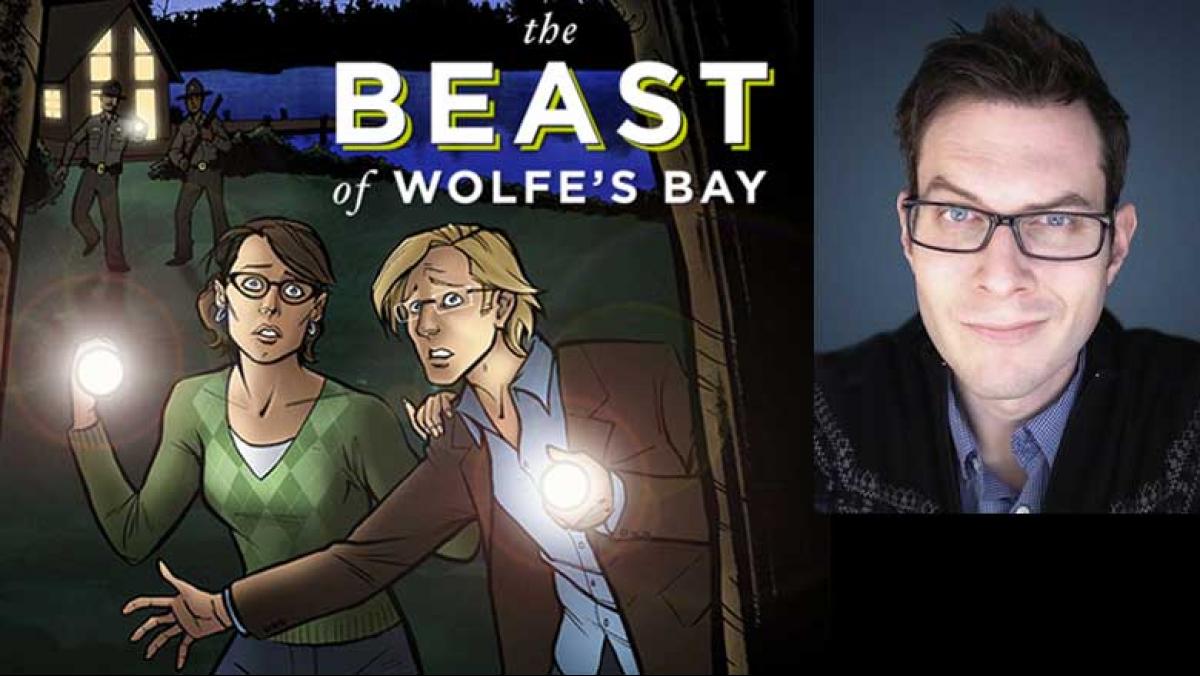

Erik A. Evensen is an award-winning designer, illustrator, and graphic novelist, and a professor of Design at the University of Wisconsin–Stout. He is the author/illustrator of Gods of Asgard: A Graphic Novel Interpretation of the Norse Myths (Jetpack Press, 2012), The Beast of Wolfe’s Bay (Evensen Creative, 2013), and Super-powered Word Study: Teaching Words and Word Parts through Comics (Maupin House, 2013), and recently illustrated a short story in IDW Publishing’s popular Ghostbusters series. Evensen holds an MFA in Design from Ohio State, and he studied art at the University of New Hampshire and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

JS: Why did you choose graphic illustration as your medium for telling stories?

EE: My love of drawing and illustration is what got me into graphic design in the first place, and comics were a big part of that. Comics got me into art, which took me to art school, which pointed me at design. As for telling stories, I’ve always been a very visual person, and as a kid I read comics with as much sincerity as I read novels. Once I discovered what a graphic novel was—a long-form, stand-alone comic book—I knew I found my medium.

I’m an illustrator, first and foremost. My education and training is all in the fine arts, and because of this, it made more sense for me to become a storyteller through a visual format. I was always good at writing, but it’s not nearly as natural a process for me as drawing.

JS: Your critically acclaimed graphic novel The Beast of Wolfe’s Bay follows the adventures of a paleo-anthropology grad student named Brian Wegman and is set at an idyllic college that looks strangely similar to UW–Stout. Did you draw any influence from Wisconsin for this tale?

EE: I’ve only been at UW–Stout for a year, so it’s actually just a coincidence. The town of Wolfe’s Bay is meant to be an “everytown” of sorts, and I never actually claimed its location in the book. But it’s based just a little bit on Bemidji, Minnesota, where my wife taught for four years. I wanted to capture that vibe of a small college on a lake in the woods, and the Upper Midwest is great for that. Much of the plot was actually hashed out while trudging through Lake Bemidji State Park. I also took a lot of influence from the lake towns in New Hampshire, too, especially visual influence. I’m originally from New Hampshire, and my family owns a lake cabin there. I moved away when I moved to Ohio for grad school, which was when I started to feel like an outsider in my own hometown. That was kind of what I wanted Brian’s experiences to feel like.

EE: I’ve only been at UW–Stout for a year, so it’s actually just a coincidence. The town of Wolfe’s Bay is meant to be an “everytown” of sorts, and I never actually claimed its location in the book. But it’s based just a little bit on Bemidji, Minnesota, where my wife taught for four years. I wanted to capture that vibe of a small college on a lake in the woods, and the Upper Midwest is great for that. Much of the plot was actually hashed out while trudging through Lake Bemidji State Park. I also took a lot of influence from the lake towns in New Hampshire, too, especially visual influence. I’m originally from New Hampshire, and my family owns a lake cabin there. I moved away when I moved to Ohio for grad school, which was when I started to feel like an outsider in my own hometown. That was kind of what I wanted Brian’s experiences to feel like.

JS: Gods of Asgard, your graphic adaptation of selected Norse mythology, and The Beast of Wolfe’s Bay, which is your take on Beowulf, both reflect a deep knowledge of and commitment to mythology. When did you first begin to “make it your own” through graphic adaptation?

EE: My family gave me a copy of Edgar and Ingri Parin D’Aulaire’s illustrated Norse Gods and Giants in the mid-1980s when I was a kid, partly, I think, to connect me with my roots. My grandfather was Norwegian, but I grew up in New Hampshire, where—unlike Wisconsin—Norwegian wasn’t a very common cultural heritage to have. I was completely fascinated by the book, and as I got older and realized there were more stories out there. I just kept consuming them when I could, and internalized it all.

When I was about thirteen or fourteen, I had the idea to adapt the Norse myths into some sort of comic format, and I even drew a few pages. While I drew pretty well at that age, I quickly realized that I was out of my depth. So, I waited until I had attended a couple of art schools before I picked it up again in my mid-twenties.

The Beast of Wolfe’s Bay is the tale of Beowulf, but it’s deconstructed and reassembled in a modern setting. For this book, I decided to make it my own, so to speak, because there were already a few straight adaptations of Beowulf out there. Gareth Hinds’ graphic novel is sort of the definitive one. I didn’t want to muddy the waters with yet another adaptation, so I decided to take Michael Crichton’s 1976 novel Eaters of the Dead as inspiration and started thinking of ways to take it apart and turn it into something new.

JS: You worked with composer Andrew Boysen Jr. and conductor Erika Svanoe (who happens to be your wife) on an original musical composition that was performed against an illuminated backdrop of your hand-drawn images. How can interdisciplinary collaboration like this expand our understanding of something as archaic as Norse mythology?

EE: Well, “Twilight of the Gods” was a success mainly because of Andy’s outstanding score. He really pulled out all the stops for that one, and I’d say it’s some of the best work of his career. And of all the conductors who commissioned the piece, Erika is perhaps the one who knows the ins and outs of it as well as we do, because she absorbed a lot of the creative process just by living in the same house as me.

The combination of music and motion graphics hadn’t really been done this way before. I mean, it’s been done, but not quite like this. Usually a composer selects a piece of art and writes a response to it, or vice-versa, as kind of a creative exercise. We were really collaborating, working through the story together and reacting to each other’s ideas.

I think that in some ways, these kinds of collaborative, cross-disciplinary projects represent the future of the arts. We often get stuck in thinking that a piece of music has to be a certain way, or visual art has to be presented in a frame or on a wall, and that’s really not true at all.

With “Twilight of the Gods,” we also wanted to create something timeless, a performance that was as much modern as it was traditional. Andy’s musical style and my art style are both rather modern, of course, but the mythology is ancient, and hopefully we were able to give it the gravitas it was due.

JS: I saw that you were co-author of an educational, comics-based textbook called Super-powered Word Study. How can the power of graphic illustration be harnessed for teaching purposes?

EE: Essentially, co-author Dr. James Bucky Carter and I were working with word parts and vocabulary, using the dialogue in the stories to illustrate appropriate word usage through short, engaging comic mini-narratives. The process of composing a narrative forces you to think about storytelling in a step-by-step, procedural way, which is a very important aspect of design. But really, you can do this with any sort of topic. I use this concept when I teach Design Drawing at UW–Stout, and incorporate broader design concepts by working them into the process of drawing sequential narratives.

As for the teaching power of graphic illustration, the big answer is that it is excellent at providing context, which allows the viewer to absorb a large amount of information very quickly. Readers are presented with information in a clear and sensible way, and get to see it applied without being forced into an uncomfortable or repetitive classroom exercise. As the adage says, A picture paints a thousand words.