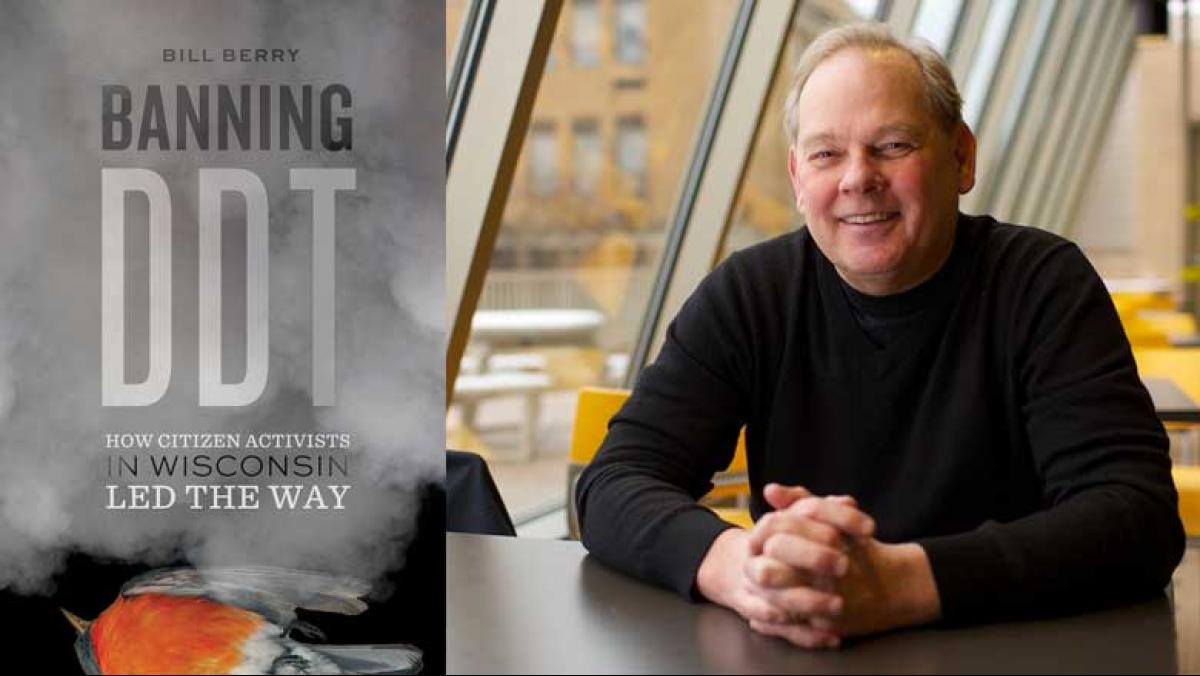

In his new book, Banning DDT: How Citizen Activists in Wisconsin Led the Way, Wisconsin writer Bill Berry manages to turn one of the state’s most historic—and perhaps longest—environmental battles into what sometimes feels like a fast-paced thriller.

Seasoned environmental activists know that large-scale campaigns are often marked by long periods of waiting for court decisions, government action, or the completion of scientific studies. So it was with the long fight to get the pesticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, or DDT, banned in Wisconsin and the rest of the country.

The first shots of the battle were fired as early as the mid-1940s when birdwatchers with the National Audubon Society issued early warnings of bird deaths. The ultimate resolution of the conflict didn’t come until 1972 when the federal government banned the dangerous chemical.

But Berry skillfully telescopes this history, and brings drama and suspense to his tale by using detail to immerse the reader in the early 1960s, when the battle started taking over headlines. The full power of Aldo Leopold’s ecological insights were reaching the general public at this time, and the 1962 release of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was a salient moment that informed and emboldened DDT opponents in Wisconsin and beyond.

Berry does a good job of placing the DDT campaign in its rightful place in our nation’s environmental history. And he does an especially fine job of establishing the effort to ban DDT as the foundation for much of Wisconsin’s modern environmental activism.

The battle over DDT saw the emergence of several now-familiar organizations and names in the state’s natural resource firmament. Important advocacy groups, such as the Citizens Natural Resources Association, came into their own, as did future leaders on natural resource issues like University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers Hugh Iltis and Joseph Hickey, for example, and so many others who would continue to stir things up in Wisconsin for years to come.

In many ways, Berry’s recitation of this story is a familiar one. But, in this case, David is going up against multiple Goliaths: the very powerful pesticide industry, a university where researchers relied upon millions of dollars from the pesticide companies to fund their research, and a state in which agriculture is zealously protected as a key part of the economy.

Berry correctly zeroes in on two aspects of this fight that would turn the tide against DDT: the fierce dedication of grassroots activists and the diligence and courage of scientists who patiently built the scientific case against DDT.

The threat posed by the pesticide first came to light when ordinary citizens took it upon themselves to confront government officials over a frightening development—robins and other songbirds dropping to the ground in their backyards, twitching and dying after DDT applications to treat ailing elm trees.

In the Milwaukee suburb of Bayside, housewife and birdwatcher Lorrie Otto was horrified. A long-time gardener and expert on native plants, Otto did not waste any time in making the plight of the dying birds a public one: she dropped off a load of twenty-eight dead robins at the Bayside Village offices (it would be the first of many such deliveries).

So many other birdwatchers took up the cause that pesticide proponents began talking about all the “old-lady birdwatchers in their tennis shoes.” It was a pejorative label that the citizen activists eventually adopted with a certain amount of pride. Years later, when invited to receive an award for her environmental advocacy, Otto would show up in slacks and the trademark tennis shoes.

Equally interesting is Berry’s description of how scientists connected the dots between DDT, thinning eggshells, and declines in bird populations.

Leading the way in Wisconsin was Joseph Hickey, a UW–Madison student and disciple of Aldo Leopold’s. Hickey would spend years building his case, frequently in the face of opposition from his employer. Berry recalls how long-time activist Gene Roark described Hickey weeping as he told Roark that his findings on DDT and bird deaths were being suppressed by the UW–Madison College of Agriculture. Hickey and his students had conducted surveys that showed widespread bird deaths in the wake of DDT treatments. In 1959, for example, Hickey and his students found in a survey that 86 to 88 percent of all robins on campus had been wiped out.

Eventually, Hickey would connect DDT to dwindling peregrine falcon populations, proving that the chemical caused thinning and breaking of eggshells in the nest before young could be hatched. The same phenomenon would be connected to precipitous drops in populations of other raptors, such as bald eagles.

All of these various components of the DDT story should sound very familiar to those in Wisconsin fighting battles on any number of environmental fronts—from the northern forests, where a giant iron mine threatens the natural resources of the Penokee Range, to the farm fields of central Wisconsin, where residents struggle to protect their water from the explosive growth of huge industrial dairy operations.

Berry’s book is a must read for those engaged in such battles. It is, by turns, inspirational and entertaining. Perhaps more importantly, Banning DDT provides lessons in how to patiently carry on in the face of powerful, entrenched bureaucracies that, whether through inertia or corruption, turn a deaf ear to the ordinary person who finds a dead bird in their yard and wants to know why.