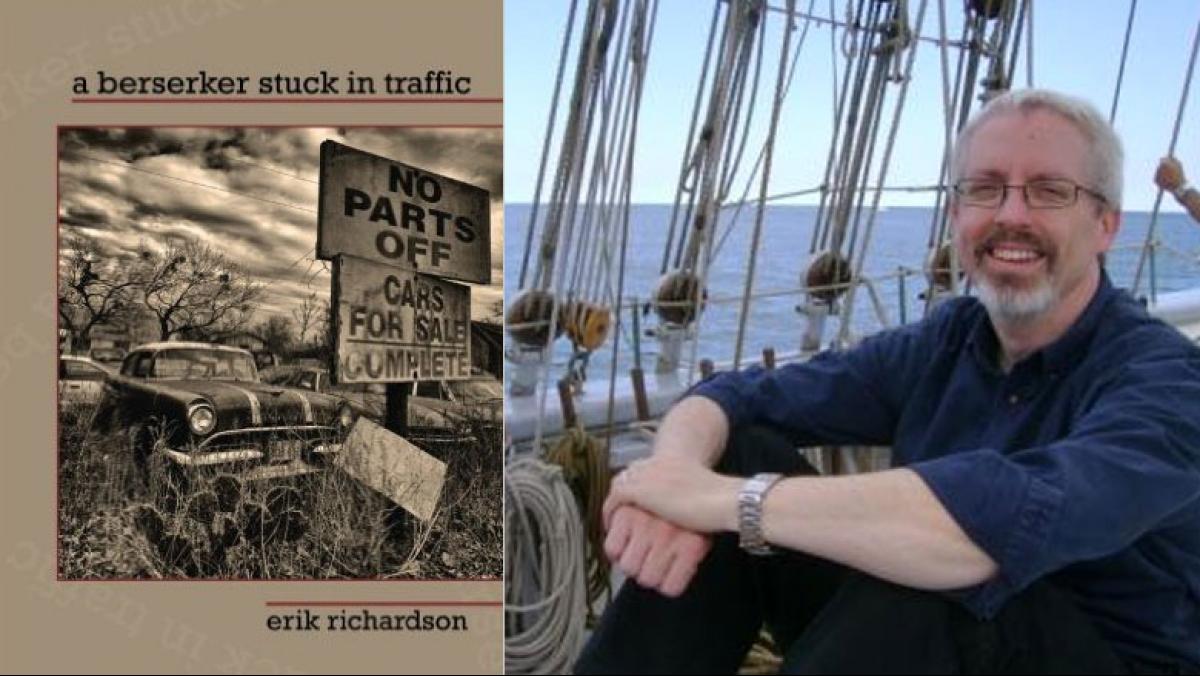

Last Christmas, my husband gave us an Ancestry.com DNA test. I knew there was a lot of Norwegian in him. Little did I know that I had some of the Norse in my DNA, too. This might explain why I especially enjoyed Erik Richardson’s new collection of poems, a berserker stuck in traffic.

Berserkers were said to be Norse warriors who fought with a trance-like fury, hence the origin of the word berserk. Richardson’s poems are made of a bit gentler stuff, but they manage to sneak up on readers and, like a Valkyrie, whisper in your ear: be wary, be afraid. These berserkers are pop culture, the person in the next cube, the woman in the express line with six-too-many items, or, as the eponymous poem of the collection suggests:

[…] at a desk, staring at a screen.

standing in a long, slow line at the store

when a valkyrie whispers in your ear,

“you were not born for this.”

you remember that your bearskin shirt

is stashed in the bottom of your dresser,

but the trance is on. […]

These are everyman/woman poems, the howl of the little and small: the teacher, the scientist, the child, the motherless son. An accomplished wordsmith, Richardson crafts poems rife with story, filled with momentum and the music of a good tale. Though he uses little punctuation, Richardson leads readers through his poems using words, pauses of syntax and line. Here’s a sample from “suburbaphobia”:

perched on the edge of 92nd street

stressed for infecting my neighbors’ yards

with wind transmitted diseases—

incriminating dandelions point back to me

even in the dark—I have no clear idea

what time the sun died today or will rise again.

Richardson is a skilled storyteller, incorporating mythologies of the Irish, the Norse, and the Greeks. He also manages to weave his tales, using math and science, the voices of Hemingway and Merton, the soft whispers of Heaney, and the mystery of the Bhagavad Gita.

In this collection, Richardson asks big questions—how does a man of heart and principal, a man of spirit, a man of words, live and live well?—yet understands that the answers are tempered by our quotidian existence. In “on the dangers of reading the bhagavad gita during my lunch break at the office,” he asks

what use to us, o computer,

are promotions, delights, or life itself?

However, his conclusion, like much of the work in this collection, transcends the moment:

when one is free of individuality

and his understanding is untainted,

even if he quits his job,

he does not quit and is not bound.

As such, all is not lost in Richardson’s poems. And he hasn’t gone entirely mad. There is humor amidst the banality, and there are constellations of wondrous light.

In “a berserker stuck in traffic,”

the light goes green. the line moves on.

your morning meds kick in

pulling you down like dwarf-forged chains, the rage

that would have once made you holy, battle-favored

of the hanged god, fading. pretend: you are just an accountant.

poems of the skalds were not true. a sword in the trunk

of your car is a really. bad. idea.

Savoring Richardson’s poems in this lovely book is a good idea. A really. Good. Idea.