Curator, photographer, librarian, archivist, Monuments Man, teacher, philosopher, flaneur, iconographer—Paul Vanderbilt was all these things. No matter what his specific role in life and work, primarily, and most distinctively, he was a proselytizer for “the notion of photography as an alternative ‘language.’”

It was Paul’s talent as meta-librarian—organizing vast troves of visual material and then parsing the ideas and interpretations therein—that lead Roy Stryker of the Depression-era Farm Security Administration Historical Section (later the Office of War Information) to hire him to arrange and classify the Section’s photographic collection. When the largely uncharted collection of FSA-OWI photographs was transferred to the Library of Congress in 1944, Paul went with it as Curator of the newly formed Prints and Photographs Division. He transformed this monumental photographic survey into an innovative historical resource, today treasured as much for its ability to suggest surprising connections and new directions for study as for the many indelible images the survey contains.

Paul remained at the Library of Congress until 1954, when he left to join the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, where he established its Iconographic Collections. There, he continued his intuitive, unorthodox approach to organizing the enormous miscellany of visual materials. In the course of his remarkable career, Paul revolutionized the way this miscellany can be seen and understood—and, in doing so, turned the archival process into an art form of its own.

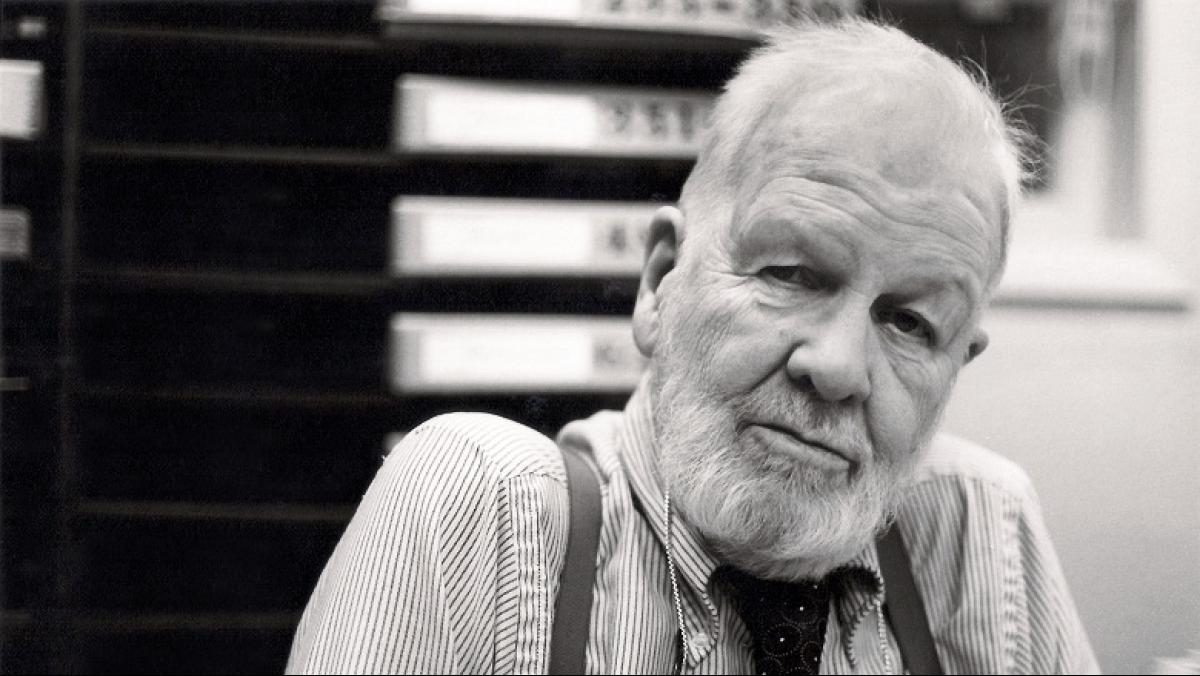

It was only toward the later part of his career that Paul became a photographer himself. I came to know him late in his life and early in my own photography career. This was in the late 1970s and by then Paul had assumed legendary, if largely unheralded, status in the realm of iconography—a field which he helped to establish in his various roles as archivist, photographer, and teacher.

This was a time when photography was achieving a certain amount of fashionable acceptability, even prominence amongst an increasingly image-savvy public. Yet decades before Marshall McLuhan and a slew of public intellectuals began to contemplate a widening construct of image interpretation, Paul had been presenting the case for a photography where answers are never so important as the prompting of questions.

“I want to argue that photography is not just for photographers,” he wrote in a 1978 article titled, “A Few Alternatives,” for The Massachusetts Review. In this article Paul staked his claim that it is not necessary to produce pictures in order to practice photography. “The making of the tangible paper photograph is but its birth, the beginning of its life as a picture,” he wrote, “what follows more significantly is among those who see that picture and in the eventual collective, generative power to which it contributes.”

Rather than making portfolios or work in series (as was current practice at the time, and still is), through the practice of iconography Paul demonstrated the diverse ways in which photographs could interact with one another as metaphors for a wider understanding of the world and things seen. Paul augmented this “generative power” by using text in tandem with his photographic arrangements, creating thematic panels that suggested novel ways of considering large arrays of images.

In the introduction to his unpublished memoir, Paul wrote that “we are all collectors of unnamable unities both of the material things attached to our personalities and, more poignantly, of experience and the innumerable details, originally disparate, that are joined to form our memories and take on a community with their association with each of us. … This reshuffling and re-creating does not lead to statistical knowledge, but, with or without incantation, it too is powerful magic.”

Paul was a quiet raconteur, and the assuredness with which he spoke his opinions was not to be taken lightly. He always gave me the impression that our friendship was one of mutual regard, though I clearly remember feeling a respectful distance, being undeniably in awe of his years of experience and gained wisdom in the many areas of our shared interests.

His handwritten list of “What Went Wrong in Photography” (right, click to enlarge) was something he had enumerated for one of his lectures, and which he bequeathed to me as both a manifesto and—I suspect—an admonition. It remains in my personal archive a treasured document, clear evidence of Paul’s incisive intellect. His list is revealing, as much for what it contains as for what it does not.

As a more extended testament, his posthumously published book Between the Landscape and the Other (Johns Hopkins, 1993) presents the fundamental and ground-breaking Paul Vanderbilt: audacious in his claims, certain in his methods, and innovative in his use of the photographic image. In Between the Landscape and the Other, Paul describes how he selects and organizes photographs for display and explains his own approach to landscape photography, all the while providing ongoing commentary on art, photography, landscape, language, psychology, values, and much more. While Paul passed away during the final stages of the book’s production, it is an elegant summation of his lifelong convictions and a fine introduction to his alternative language of photography.

In looking at the thematic panels, it becomes clear that Paul was testing and refining the vocabulary for his new language. In these arrangements he was substituting a sensorium of ideas, both visual and textual, for anything more specific or connotative. Through his doubts about prescribed “meaning” and literal “truth,” I came to understand that much of what Paul was advancing was driven by a strong sense of wonder and the sublime:

The capacity I most value of all my fortunes, the constant I would be most grieved to lose … is the enjoyment of almost everything I see about me, in some one of the myriad forms of possible enjoyment, many of which are not allied to approval, but, philosophically, to the wonder of being, complete with all its illusions.

This quote, excerpted from Paul’s Unpublished Introduction (1982), is deeply resonant with incipient ideas I was working on then—and continue to explore today—in photo-assemblage and use of text with images. For me, the gravitational pull of Paul’s intellectual rigor was an undeniable force.

Storytelling and its visual corollary—that of looking around, making images—were the vehicles for what he called, a “fresh endowment of wonder.” In his own photography, Paul was clear-eyed and present in the moment. Yet his single images were not a “decisive moment” so much as a still point, and his photographs are today highly regarded for their artistic vision.

However, the radical nature of Paul Vanderbilt’s ideas has yet to be fully absorbed by image-makers and the viewing public alike: specifically, that the piecing together of disparate moments leaves open the possibility of engendering further questions and new directions of thought.

For Paul, in his recombinant approach to visual materials, answers were never so important as the prompting of questions. He argued for leaving the “front and back [open for] another question. … [As such] we may have to conclude that meaning is by nature elusive, say ‘No’ to those who insist, and settle for whatever charge is felt from the original intuition.”

Paul recognized that pictures happened in many and various ways, whether by intention or happenstance, and that they in no way represented any one thing. Mutable, obscure, reflective, neither mirror nor window, but perhaps both—

The life of a picture begins when it is finished and what happens to it at that point on out is both more important and more interesting than the circumstances of its meaning coming into being.