Dr. Merton gave Shelby Aronowitz bad news. The pain in her knee was osteosarcoma. They would have to amputate.

“Can’t they replace it?” Shelby’s mother said. “Just the knee?”

“No,” Dr. Merton said. “We have to remove bone too far above and below the joint.” He brought up an x-ray, and an image from Shelby’s MRI. On the large screen in the small room, he pointed at dark spots on the pictures. “See,” Dr. Merton said. “Maybe if we had caught it sooner …” He cleared his throat. “You can be fitted with a prosthetic leg. The technology is evolving quickly. There is no reason you can’t have a full life.”

Shelby’s mother wrapped her arms around Shelby’s broad shoulders and started to cry. It was a weak embrace. Shelby wanted to slap her, tell her to straighten up, to go lift some fucking weights. Even here she pictured her mother still in bed, propped up with pillows, a box of Kleenex on her lap, whining on the phone to Aunt Arella about her pains.

Dr. Merton continued, “Ride a bike, dance, even run. You have a very strong physique.”

Shelby pulled away from her mother and stretched out her leg. She leaned over it, rubbed it, dug her fingers into the flesh, methodically massaged from the calf to her upper thigh. Three times. Her leg felt warm, alive.

“I want to keep it,” Shelby said. She looked at Dr. Merton’s face. It reminded her of the fudge cheese her Aunt Arella gave her; Shelby chewed it and was frustrated that she couldn’t taste the fudge or the cheese, so she spit it out. She tried to guess if Dr. Merton was about to smile, or frown. Why would he smile?

“Not recommended,” Dr. Merton said. “It’s localized now, but it could spread into your organs, your brain.”

“No,” Shelby said, “I—”

“You’re seventeen.” The doctor straightened. “Go with the surgery and there is no reason you don’t live to be one-hundred. Without this surgery. …”

The doctor pushed a button and the screen with her pictures went dark. “I don’t want to scare you, but you would be dead by your twenty-first birthday. Maybe sooner.”

“No,” Shelby said. “I want to keep the leg.”

“Shelby,” her mother said. “For God’s sake, listen to the doctor.”

“No. You listen to me,” Shelby said. “I want to keep my leg.” She stood up. “After the surgery.”

Dr. Merton squinted. “It has to come off,” he insisted.

“After that,” Shelby said, “After the surgery … I want to keep it.”

The doctor sighed, rubbed his eyes with both hands. He put two fingers down his collar, above his tie, and tugged.

“This is crazy talk,” her mother said. “Why?”

Shelby shrugged. “I don’t know. I just do.”

“Impossible,” her mother said. “Right, doctor? Tell her.”

Dr. Merton looked at his watch and stood up. Just one hour left in the day and three more patients to see. “Alright,” Dr. Merton said. He turned to Shelby’s mother, tried to recall her first name, but could not. “Believe it or not Mrs. … Well, there is a protocol for Shelby’s request.” He cleared his throat. “As a minor she needs your approval. Some papers to sign. Additional costs.”

“Never,” her mother said.

Shelby put her hand on her mother’s shoulder. “Then I die when I’m twenty-one.” Shelby

looked up at the doctor. “Or sooner.”

• • • • •

The phone rang and Shelby’s mother answered it. “You should know something.” She recognized the voice as Jacob, her dead husband’s brother. “I talked to Shelby. She wants me to sue you.”

“But I’m her mother.”

“Tell me something I don’t know,” Jacob said. “It’s about the leg.”

“Of course it’s about the leg.” She wanted to spit. “I wish we were born with … with fins. I hate this leg.”

“She told me the disease has changed her,” Jacob said. “No more writing; she wants to go into law.”

“What about the leg.”

“Can’t you imagine Shelby and my little Zeke, the family business living on? Benjamin and I had discussed this many times when he was alive. Of course we thought it would be our sons. Dreams of patriarchal fools; the times have changed. Shelby would be perfect. Your Benjamin, my brother, is smiling.”

“You are not seriously considering this,” she said.

“I am. Aronowitz and Aronowitz. I thought it would end when Benjamin passed, but now it could live beyond us. The Psalm that Benji loved so much: One generation shall commend your works to another, and shall declare your mighty acts. This disease is a gift from God himself.”

“I mean suing me.”

“Of course not,” he said. “But she has a case. This is why I called you. I agreed to work with her. I explained that I did Mergers and Acquisitions, not personal suits. There is a lot of money to be made in divorce, estate squabbles, but. … No, I will not be part of that. I will never set one man against another.”

“What do you mean work with her?”

“I’ve researched it,” Jacob said. “You need to know that there is no law against keeping the leg, or any body part, in our state. Some states: Louisiana, Georgia, Missouri, it is against the law. But even there, if you are part of certain religious groups that believe the body is physically resurrected, as when the Christ returns, you are allowed to keep these parts to be buried with you. I guess they are put back together.”

“Jacob, do you hear yourself?”

“Even in states where there is no law against this—I have it right here—the Native American Graves Protection and Reparation Act makes it illegal to own or trade in Native American remains. It’s unclear to me if this applies to Native American individuals and their own body parts. But that is not our problem here.”

“I’m tiring of this conversation.”

“I called to let you know a reporter was here,” Jacob said. “From The Sentinel.”

“About Shelby?”

“Not at first,” Jacob said. “He wanted to interview me about the Brazilian acquisition of Madison Dynamics. Brazil is such a hotbed of innovation. It will bring jobs into the city. One of our biggest projects.”

“The reporter?”

“He was a nice man,” Jacob said. “Young, but nice. I couldn’t answer most of his questions. For legal reasons. Then Shelby called, right when he was in my office. I was so happy about her intention to go into law that I told him what she told me.” Jacob paused. “I thought the leg thing might have been a joke. Benjamin was always a practical joker. I never knew when to believe him. Maybe it rubbed off on her. The reporter is going to talk to Shelby. I guess her leg is news.”

“My God, Jacob.”

“I may have made an error in judgment,” Jacob said. “But she’s not legally my client yet. That’s why I called you.”

“My God.”

“You’ve got Benjamin’s ashes on the mantle in your living room. I don’t see harm in letting Shelby hang her leg on the wall of her bedroom. What harm?”

Shelby’s mother ended the call. She imagined her daughter’s leg, mounted, hanging above the bed. She wondered if it would be visible from the street, at night, when the light was on and the shades were up.

• • • • •

Shelby was not interested in talking to the reporter. Neither was Dr. Merton. Nor was Shelby’s mother, nor her Uncle Jacob. Especially Jacob, who felt he had done enough damage already. Despite having very little information, the reporter’s article ran the following Sunday, in the community section of The Sentinel.

“I want you to sue them,” Shelby’s mother said.

“There’s nothing slanderous or fallacious in the article,” Jacob said. “We have no legal grounds.”

“I’m afraid Shelby is taunted at school.” Shelby never brought friends over for dinner, or to study, the way her mother’s friends talked about their children. Shelby’s mother knew that Shelby was busy with lots of extracurricular activities, but worried that she might not have even one good friend to confide in.

“Jacob, she barely talks to me. At dinner she tells me a boy, a hunter, offered to mount her leg, like a deer head. I think she wants to torment me, to drive me mad.”

“This is normal for a girl her age,” Jacob said. “And all this stress.”

“Now,” Shelby’s mother said, “we’re getting calls from other reporters. And the TV wants her to come in and be interviewed. I’m losing my mind. I can tell from the way she looks at me that she enjoys it.”

“I’m sorry, but—”

“You were going to sue me,” Shelby’s mother said. “Sue them.”

“I was never going to sue you,” Jacob said. “But listen to me.” Jacob started to punctuate his phrases by jabbing a finger at his sister-in-law who was across the city. “She’s threatened to go find another attorney if I don’t. And I’ll tell you, they will come from all over the country for this case. For free.”

“What can I do about this?”

“Sign the consent form,” Jacob said. “She needs the surgery. You’re holding her back.”

“It’s an abomination,” she said.

• • • • •

Shelby sat on the edge of her bed and straightened out both legs. She thought the right one, the cancer leg, was a little shorter than the left. Her knee hurt. She tried to understand why she wanted to keep the severed limb. She’d felt a small voice in her, a call to keep it.

Her phone rang.

“Hello,” Shelby said.

“Am I speaking with Shelby Aronowitz?” The caller had one of those smooth, low-toned voices, a late-night radio voice, that sent a wave of comfort over Shelby.

“Yes,” Shelby said. “Who is this?” She settled back and shut her eyes. Her shoulders dropped, a puppet with the strings cut.

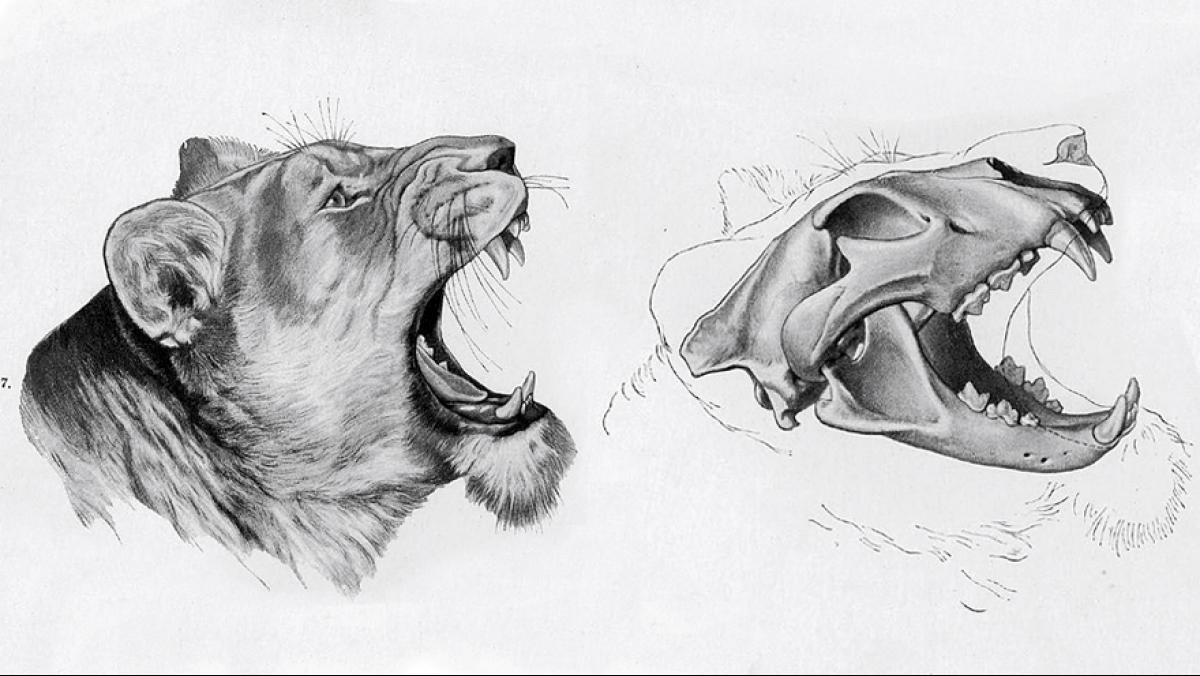

“My name is Glen Smith,” the caller said. “I work for—actually, I own—Casselton Skulls. We’re a company that specializes in the preservation and sale of bones: mostly skulls, animal skulls, and some full skeletons, mostly animal skeletons.”

Shelby sprang alert. “Is this a joke?” She tried to place the voice. “Who is this? How did you get my number?”

“Please, Miss Aronowitz, this is not a crank call. I’m guessing you’ve had quite a few. We are one of two companies in the states that deal with human bones. Well, there are others that work for the medical industry, and we do that, too. But we also handle private needs of your type.”

Shelby thought he sounded like the men from the funeral parlor, who’d met with her mother after her father died. There was sincerity and solemnity in his tone. Shelby knew this must be part of the job, special training in bereavement. But she wanted to believe that he was genuine, that he understood and cared.

“When you say my needs, what do you mean. Exactly?”

“We can receive your leg from the surgeon. We would discuss the preparation with him in advance. Many times the surgeons butcher limbs as a matter of convenience, cut them into pieces. But we would ensure separation from the body is … done with respect. If you wish, we can have one of our people present at the procedure.”

“What … then?” Shelby realized she hadn’t thought through the transition of dead flesh to bone. She remembered a childhood friend who snapped a pencil eraser off in his ear and needed surgery to have it removed. He kept the eraser in a plastic pill bottle and brought it to school. The neighbor across the street had the head of his first buck mounted, a seven pointer. But it still had its eyes and skin. She’s always assumed the eyes were glass and the fur was real.

“Am I going too fast for you?” Glen Smith said. He paused, let out a slow breath. “I know this is a lot to take in.”

“You’ve done this before?”

“Yes. We don’t deal with soft tissue: breasts, ovaries, intestinal lengths, or such foreign matter as gallstones and tumors. Just bones: hips, knees, feet, hands, even once a … well…we’ve never had the privilege of a full limb. You’d be our first.”

“How much does this cost?” Shelby remembered Dr. Merton mentioning additional charges.

“It might seem insensitive to charge you. Not charging you would set a … precedent. Everyone would expect the same. We are prepared to give you a thirty percent discount. Our fee of $3,000 would be reduced to $2,100. And, should you want one, we would provide an observer at the procedure for no charge.”

“Why so much money?” Shelby wanted to know. “My friend had a deer head mounted, eyes and fur added, for just $400.”

“Here’s our process: after removal and transportation, we deflesh the limb with Dermestid beetles, a very common practice in this industry. Then, of course, we sterilize and whiten the bones,” Glen Smith paused.

“What do you do with the beetles? When they’re done.”

“Good question. After skeletonization is complete, we keep half the beetles and associated larvae; we release the other half back into nature.”

“Could I choose where the beetles are released?” Shelby said.

“We’ve never had that request,” Glen Smith said. “I’m sure we could work it out.”

“I like this,” Shelby said.

Glen Smith continued to explain. “Next, we wire the bones together to ensure long-term stability of the body element. And there are quite a few bones: four in the knee, fourteen in the ankle, and thirty-eight in the foot. Labor intensive stuff. I’m assuming you want the leg intact, versus a box of bones, which we could do at a greatly reduced rate.”

“I want the leg in one piece,” Shelby said.

“Very good, Miss Aronowitz. We would suggest that.”

“I need to talk to my mother about the money.”

“We’ve handled that for you,” Glenn Smith said. “Have you heard of the Mutter Museum, in Philadelphia?”

“Doesn’t ring a bell,” Shelby said.

“They have a large and varied collection of human artifacts. About three thousand. Wet and dry.” Shelby wondered how they distinguished between wet and dry. Was it how it arrived, or how it was displayed?

“Even,” Glen Smith continued, “parts of Einstein’s brain and John Wilkes Booth’s spine.” He waited for a reaction from Shelby: a Wow, or That’s crazy, but nothing came. “They have offered to pick up the cost if you agree to will them your leg, to be delivered after you die.”

“Why would they want to do that?” Shelby said. “I’m not famous.”

“Why do you want to keep your leg?”

“I’m not sure,” Shelby said.

“The answer is part of the same mystery,” Glenn Smith said. “It’s a feeling, a calling, a notion that some things, some actions are significant.”

“I’ve felt that,” Shelby said.

• • • • •

Shelby’s mother finished her dinner quickly and started to wash the dishes. For almost forty minutes neither she nor Shelby had spoken a word. Shelby broke the unspoken truce. “Mom. No charge. Casselton Skulls does this full time.”

The plate smashed on the kitchen floor. Pieces went everywhere. It wasn’t from the good china in the front room cabinet, the tableware used for holidays and guests; this was an everyday plate. They broke now and then, usually a forgivable accident. But Shelby’s mother had thrown this one: a ferocious, overhand gesture.

“What the hell, Mom!” Shelby was not as much upset as surprised: to see the red in her mother’s cheeks, her sharp athletic movements. Shelby suppressed her smile.

“I’m tired,” her mother said. “Fuck all these reporters. Fuck your uncle, my friends, the school. Who is this guy who’s going to mount your leg? You—Are—Dying. You need surgery. First your father and now I’m supposed to lose you? For this fucking leg? Fuck your leg. Fuck everybody. Fuck you.” She pitched a glass at the floor.

Shelby shielded her eyes from the ricocheting shards. She had a moment of doubt. Should she will her leg to a museum? Might not one of her own children want it? A relic, an heirloom, to be passed down generation to generation—a part of her that would live on. She laughed at the mental picture of a family gathering, on a holiday perhaps, looking at the leg, retelling the story of this eccentric relative. Perhaps it would be shared, passed from household to household, an annual lottery to see whose mantle it would grace for the year. If relatives awakened in the middle of the night, their house burning, not a moment to lose: wake up, get out—leave the cat, leave the pictures—grab that leg.

Another glass shattered. Shelby grinned.

Shelby’s mother feared her daughter’s composure. This was more than the stubborn disagreement of an adolescent coping with loss. She decided to call Arella for help.

• • • • •

I told you,” Arella said, “you should have forced Shelby to go to counseling when Benjamin passed.”

“You’re probably right,” Shelby’s mother said. “I see that now.”

She regretted making the call to Arella, her sister-in-law. Three years older than Jacob, Arella looked ten years younger: taut facial skin, athletic, erect posture, and a throat full of advice about everything. What Shelby’s mother hated about Arella was what she now needed—Arella was always right.

“I have a guy,” Arella said. She had a guy for everything: doctors for physical ailments, counselors for mental issues, Reiki practitioners for emotional problems, a shaman for bad spirits, the tree guy, the roof guy, the garden guy, the sex advisor (“Women need to learn to be selfish in bed,” he would say).

“Can he help with …”

Shelby’s mother tried to find the word. How would she characterize her daughter’s problem? Grieving? Repressed emotional issues from childhood? Neurosis? Psychosis? She was a smart girl, good grades, no drugs, never talked much about boys, had a good relationship with her father, cried at the funeral.

“I’m not sure what to ask help for,” Shelby’s mother said.

“She wants to keep her severed leg,” Arella said. “That should be enough to clue in a professional.” Arella cleared her throat and announced, “Dr. Otto Lubitsch. Yale. Twenty-five years of experience. Helped the Wexlers’ son with his eating disorder. Strange one called pica. He used to mix in paint with his milk, made omelets with pencil shavings. Lubitsch is perfect for Shelby.”

“Paint?”

“Yeah. He even mixed the colors to complement the food,” Arella said. “Have you ever asked Shelby why she wants to keep the leg?”

“A thousand times,” Shelby’s mother said. “I ‘ve begged her to explain it to me. All I get as an answer is her middle finger.”

“Little kelba,” Arella said. “Let me give you Lubitsch’s number.”

• • • • •

You see a counselor.” Shelby’s mother said. “You see a counselor, and if he gives me the okay, then I’ll sign.”

“All right,” Shelby said. “I would like to talk to a counselor.” She stared at her mother defiantly, her agreement a threat.

“Don’t give me that look,” her mother said. “I haven’t done a thing.”

“Really?” Shelby said. “We’ll see what the counselor says about that.”

• • • • •

Dr. Lubitsch’s office was large. Dark. Slatted, wooden shades covered the windows. Floor-to-ceiling bookshelves lined the walls, pressed tight with sets of old hardbacks. Shelby looked at the books as she walked to the brown leather chair Dr. Lubitsch motioned her to sit in, and she could not recognize a single title. Shelby thought all the lights in the room needed brighter bulbs. How could he read in here? She sank into the chair. It was comfortable, enveloping her. She wanted to nap.

“Nice to meet you Shelby,” Dr. Lubitsch said. He sat on a straight-backed chair across from Shelby.

Shelby nodded in the doctor’s direction.

“Are you comfortable?” Dr. Lubitsch said. “How does your knee feel?”

“It hurts,” Shelby said. “Like a bad sprain that won’t get better.”

“Yes,” Dr. Lubitsch said. “And I understand it won’t.”

Shelby winced.

“Still holding out hope? “ Dr. Lubitsch said. “For a miracle?”

Shelby shrugged.

“That’s normal,” Dr. Lubitsch said. “I’ve seen many patients who hope for miracles, but I’ve never seen one that can’t be explained.” He shifted in his chair. “There are solutions though, based on science. The mind can work wonders. It can be tuned to work better.”

Shelby laughed. “So what do you think my problem is?”

Shelby was anxious to talk about her mother. About how she had to do everything for her mother the first year after her father’s death: cleaning, cooking, making sure her mother took her meds. About how her mother never let her use the car—even hiding the keys. Always left wondering if her mother would be there to pick her up after school activities or if she would have to hitchhike home. And how her mother was unable to make eye contact, never listening to how she felt, what she was going through. How her mother never paid any attention to her—until now.

“I never said you had a problem.” Dr. Lubitsch was a small man, perfectly proportioned, but very small. “We’re here to talk.”

Shelby rolled her eyes: she knew the deck had to be stacked against her with this guy. She tipped back her head and looked at the top of the bookshelves lining the walls. She hadn’t noticed this before. A smile erupted on her face. Skulls everywhere. Some big: one looked like a massive pig; another, the top of a horse’s head. Many had horns—straight and curved, deer, goats, rams—and there were some small ones, mainly birds, raccoons.

Dr. Lubitsch turned in his chair, looked up and around the room. “Is this morbid to you?” he said. “Does it bother you?”

“No,” Shelby said. “I like them.”

“Some don’t,” he said. “I usually meet clients in a different room. I thought you would appreciate them.”

“I do,” Shelby said. “When did you start collecting them?”

“The first was the pig over there, and then I found the horse skull in the trash. I trash pick around the university when the students move out. You can find lots of interesting stuff. It wasn’t really a collection, but people—friends, clients—started giving me skulls. The coyote is from Colorado, a woman suffering from a borderline personality disorder. The ram is from Nevada, a young man with bipolar tendencies. The large bird was from an elderly couple I treated for hoarding; their collection is vast compared to mine. The deer was from a friend, a hunter; he also gives me venison every year.”

He scanned the collection, paused here and there. “Each has a story.”

“Hmm,” Shelby said.

“I like to hold them,” he said. “Some forms of meditation, used to stop thought, direct practitioners to imagine their flesh dropping away until they are just a skeleton. Then they imagine removing their head, just a skull now, from their body, and inserting it, upside down and reversed, under their ribcage.” He rubbed his stomach. “I’ve heard it’s quite effective.”

“I can’t imagine,” Shelby said.

“Do you know what phantom limb pain is?”

Shelby nodded. “I’ve read about it.”

“Sometimes patients go out of their minds with the pain, believing that their lost limb is spasming.” He held out his hand and made a fist. “Clenching up.”

“Is there medication?”

“No. Acupuncture, massage, the mirror box,” he said. “Have you heard of that?”

Shelby shook her head.

“Let’s say you’ve lost your right arm. Imagine you are sitting to the side of a big mirror, and you insert your stump into a box behind the mirror. You are then instructed to look at the reflection of your other arm and imagine it’s the one that’s missing.” He held both his arms out. “When you stretch your good arm, wiggle your fingers, you look at the reflection and imagine it’s your other arm, the missing one. It works wonders.” He placed his arms on his legs. “As I said, it tunes the mind.”

“Do you think I’ll need that?” Shelby said. “Do they have them for legs?”

“I’ve never seen one for legs, but I expect we could have one built.” He looked at her feet, turned his head sideways, designing the device in his head. “If we need to.”

“Why does it work?”

“Some mystics think that, when we dream, that is the real world. When we are awake, that is the dream. The mind can do wondrous things. Horrible, yes. But also wondrous.”

Shelby pointed up. “Is that a cat?”

“Yes,” Dr. Lubitsch said looking up. “My Smokey. Had him thirteen years, then … well, cancer got him.”

“I’m sorry,” Shelby said.

“Sometimes I hold his skull. I feel his presence. I wonder if the seat of the soul isn’t in the skull.” He smiled. “Once a friend wanted to give me a human skull, but my wife said, No, too creepy.” He looked at her leg. “I’ve never held a human bone. I imagine if it’s your own, once part of your body now separated, something as substantial as a leg, the possible experiences are … amazing.”

She pointed again. “What is that one? Where did you get it?”

Dr. Lubitsch looked up at the large, damaged skull. “A long story.” He leaned in. “It’s fragments of an Allosaurus.”

“How old is that?”

“About 150 million years old.”

“Immortal,” Shelby said. “In a way.”

Dr. Lubitsch raised his eyebrows, and nodded.

• • • • •

Shelby watched her mother sign the papers, slap down the pen, and slide them over to Dr. Merton. “We need to schedule the surgery,” Dr. Merton said. “But.” He shook his head. “All this publicity put you on the map. I’m grateful you didn’t give interviews. Nothing is private anymore.” He looked past them to something on his office wall. “I’m OK with head shaving parties and such events as a form of support, although the ones who embrace their cancer have a higher chance of recurrence. The ones who hate it have a better survival rate.” He looked back at them. “Things are complicated enough without the press.”

“We agree on that,” Shelby’s mother said.

“I’ve been contacted by the Walton Cancer Institute in Chicago. They read about Shelby and wanted to know if she would be willing to let them examine her. See if you are a candidate for a new procedure.”

“A cure?” Shelby said.

“No. Not a cure,” Dr. Merton said. “But a less invasive treatment for osteosarcoma. Taking bone marrow, blood, growing stem cells, altering DNA using a process called a CRISPR, reinjecting the modified cells, and. … Well, like I said it’s complicated. It’s in a class of treatments called oncolytic virus therapy. Shows enough success to be credible.”

“What do you think, Doctor?” Shelby’s mother reached out and put her hand on the paper she’d just signed. “Will it save the leg?”

“I hesitate to comment,” Dr. Merton said. “This cancer is a slow spreading growth for now, but that could change. With the rise of genetic research we are in a golden age of treatment development. It’s hard to keep up. I would recommend getting an assessment.”

Shelby’s mother turned. Looked Shelby in the eyes. “What do you think?”

“Sure,” Shelby said. She looked at Dr. Merton for reassurance. One side of his mouth was turned up, the other down.

“If successful, you’ll still need a new knee,” he said.

“I’d want to keep the old pieces,” Shelby said.

“Of course,” Dr. Merton said.

• • • • •

Shelby sat on her bed drinking water. Ten to twelve glasses a day, ordered by the doctors to flush toxins from her system. Her right leg was in a tight, soft cast, and she was unable to bend it. Turning on the light, getting a book from her desk, rolling over to grab her phone off the nightstand—simple everyday tasks were painful and at times impossible. Not the least of which was sitting on the toilet, after getting into the bathroom.

Shelby’s leg hurt. Her body was hot. She was told to expect flu-like symptoms from the treatment. She had watched the long, thick needles inserted into her knee inject the brown goo they’d grown from her fluids and marrow. She was not allowed to take painkillers; the new doctors told her it had to do with prostaglandins, blood flow, and white blood cells. It would be two weeks before she would know if the procedure had taken. Even after that they wouldn’t know for sure until they opened her up and did rapid biopsies on the parts around her knee.

She was told to mentally prepare herself for the operation. She’d be knocked out, and when she woke she would either have a new knee or no leg at all. Shelby thought Dr. Merton was direct, but these younger doctors had no time for a soft step. She became nervous about everything. It was hitting her, the changes to her life.

Almost two weeks she sat in her room, immobile, waited on by her mother. Summer break had started, a bad coincidence of timing. Google this, Google that, eat, watch a Netflix movie, eat, check Facebook, check Instagram, binge a TV series, eat, check Facebook, sleep, wake up, check Facebook.

Her Uncle Jacob and Aunt Arella came by several times a week to visit and drop off food. Dr. Lubitsch offered a weekly home session. It was the first time Shelby realized she didn’t have real friends. Before the cancer her life was full of activity: she built sets for the school play, read after school to the children of single parents, coordinated fundraisers for the new gym, played tennis. But none of her school friends came by to visit.

All day, she prodded and probed around her knee. Her fingers built and updated a map. The pain moved, grew. She knew the cancer must have been spreading. It had to be. She wondered if she might die.

• • • • •

Did you expect to have more visitors?” Dr. Lubitsch said.

“I did,” Shelby said. They were sitting on two leather chairs in her father’s old study. She was glad to be out of her bedroom, finally allowed to move around. Her mother came in and gave them each a glass of coconut-flavored sparkling water. Her mother left and pulled the door shut until the latch clicked.

“Were you always so active at school?”

“After my father died.” Shelby adjusted her leg and scanned the room. Shelby’s mother left the office untouched, as it was when her father was alive. A dirty coffee mug sat on his desk, adjacent to a yellow legal pad with a cartridge ink pen lying on top. The blinds were down. It was dark. Quiet. “I did a lot more with my father than I knew. Fishing. Hiking. Talking. Once, we drove clear around the lake, one hundred miles, on a Sunday afternoon, just to do it.”

“You could be … compensating, over-functioning. A lot of activity with no meaningful connections. A behavior not uncommon when filling a void. Never a minute to stop and take a breath. Like an insect, a water strider, zigzagging on the top of life’s pond, afraid to stop for fear of sinking. Our technology, all the screens we carry, makes it easy.”

Shelby wanted to check her phone. Reached into her pocket, felt guilty, and just touched it.

“Your mother?” Dr. Lubitsch leaned back.

“I’m mean to her. I don’t know why.” Her mother’s life reminded her of Dr. Merton’s face, not quite happy or unhappy, stuck in some purgatory, waiting for some better place.

“Not uncommon for teenagers,” Dr. Lubitsch said. “Especially if the opposite sex parent with whom you had a good relationship is now gone.” Dr. Lubitsch waited to see if this registered with Shelby. “Very common in divorce.”

Shelby swirled her drink. Carbon dioxide bubbles rose to the surface and fizzed. It was a comforting sound for Shelby.

Her mother and father met in college, in the city. Married young. Shelby was born one year later. Her earliest memory was sledding with her father when she was five. He and her Uncle Jacob, both new law school graduates, were starting up their business. That night her mother was sick; she was frequently sick: the flu, a bad cold, rundown, or “feeling blue”.

Despite her mother’s admonitions, her father bundled Shelby up to take her on an adventure. They drove through a blizzard to a golf course and hiked to the 9th hole. Looking down, Shelby thought it was the biggest mountain in the world. Her father would position the red, plastic toboggan with him in the back and Shelby in the front, secured in his legs. He would launch them with a few strong pushes. The world rushed by, snow stinging her face. She screamed in delight. At the bottom they would turn and tumble off the toboggan, laughing. For a moment before they got up, her father would squeeze her in his big arms, kiss the top of her head. He told her to shut her eyes and listen, listen to the sound of the falling snow. She did. She heard it stretch in all directions. Endless. Ceaseless. Perfect. Shelby opened her eyes, looked at her father and said, “Again!”

“Shelby?” Dr. Lubitsch said.

She looked up from her glass. Scanned the room. Hunted for something. She saw the urn. “Once, when we were hiking,” Shelby said, “my father told me he wanted to be buried in a forest, a biodegradable coffin that would let his body decompose into the ground. So he could live on as part of the trees.”

“I have heard of that,” Dr. Lubitsch said. “Honorable.”

“Since then I always imagined walking through the woods, alone, or with my own children someday. Feeling his presence.”

“Where is he?”

Shelby bit her thumbnail and pointed with her head. “Right up there. Cremated.” She talked around her thumb. “My mother had it done.”

“Did she know about your father’s wishes?”

Shelby shrugged.

• • • • •

The operating room was nothing like she’d imagined: small, a low ceiling, non-distinct colors, less equipment than she expected. Each member of the team was busy with a task. Glen Smith from Casselton Skulls stood in the corner. A nurse inspected neatly lined up instruments. One doctor watched a digital loop of Shelby’s latest MRI, another positioned a camera over her leg, and another nurse swabbed her knee with something cold.

Dr. Merton stood over Shelby. He was there to assist and observe. Covered in a mask, she could not see his face below his eyes. One of his eyes was bloodshot. “We’re going to give you something to help you relax,” he said. She watched the nurse put a needle into the IV port hanging from her arm.

Shelby felt weighted down, but struggled to keep her eyes open, afraid they might start to cut before she was asleep.