Imagine a city canopied by green, a community bursting at the seams with plant life. In this place, residents and business owners swap their lawns for perennial plantings and an army of city workers manages the lush natural areas that reach across every neighborhood—regardless of socioeconomic class. Here, a once-empty lot is transformed into a community garden; there, an abandoned warehouse has been removed and turned into a forested park. Formerly sunbaked streets become tree-shaded boulevards, encouraging people to walk or bike to local businesses. Older buildings are retrofitted with rooftop gardens, and new constructions are built to maximize tree cover and minimize open pavement.

Sounds like a garden-lover’s dream, right?

While it’s true that urban greening on this level would be beautiful, in this idealized city it is happening for another reason: to fight climate change. Urban greening is one among many examples of activities known as natural climate solutions that communities—both urban and rural—around the globe are adopting. While natural climate solutions sounds like a hip new term, it’s really just a catch-all name for the many land conservation, restoration, and management practices that work to capture and store carbon found in greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane.

At a time when our world needs swift, effective action to address climate change, natural climate solutions are pragmatic options for sequestering greenhouse gases. According to a recent study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, natural climate solutions could provide up to 37% of the emission reductions needed by 2030 to keep global temperature rise under 2°C.

Part of what makes them so effective is that the infrastructure to increase the scale and scope of many natural climate solutions already exists. Here in Wisconsin, a committed group of researchers, businesses, municipalities, and citizens is already hard at work developing natural climate solutions for our cities, agricultural lands, and forests.

• • •

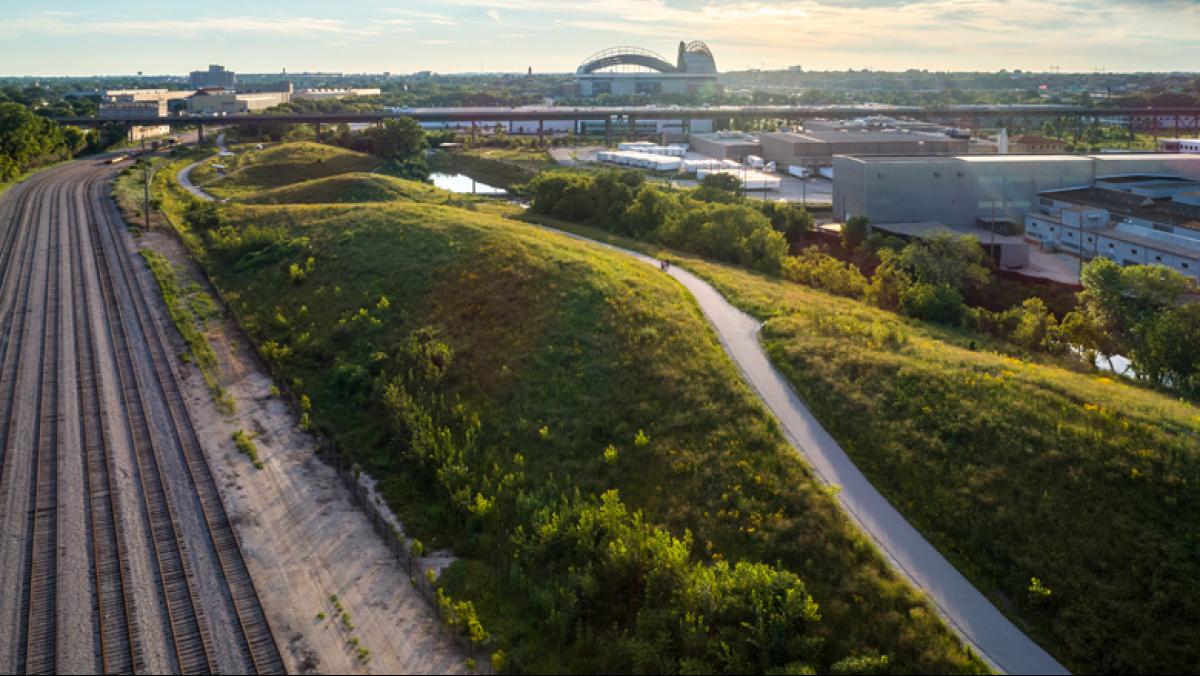

The idea of urban forestry is not new to Wisconsin. Throughout the nineteenth century, Madison and Milwaukee led efforts to plant trees and establish public natural areas. The leaders of these efforts viewed urban forests as important mainly for their aesthetic value and as a place for the public to enjoy nature. While these values remain at the core of many urban forestry efforts, city planners, researchers, and urban residents today recognize a much broader suite of benefits that includes carbon sequestration. Because they do an efficient job of removing carbon from CO2 and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and sequestering it in their roots, trunks, and branches, trees are primary tools for natural climate solutions.

Today, communities across Wisconsin are heavily investing in tree planting projects with climate in mind. Abe Lenoch, Community Project Coordinator at 1000 Friends of Wisconsin, is currently working with four cities—Ashland, Bayside, Oshkosh, and Sheboygan—to expand their urban forest canopies through a collaborative planting initiative. These cities are all Green Tier Legacy Communities, which means that they are working with state agencies and nonprofit organizations to develop and implement long-term community sustainability plans.

According to Lenoch, these cities planted their trees to address both the long-term threat of climate change and a more near-term one: flooding. Trees can efficiently mitigate flooding. Lenoch explains, “Leaves intercept rain on its way to the ground, which … reduces the infiltration rate of rain into the groundwater,” giving the ground more time to absorb the water. The four Green Tier Legacy Communities selected climate-resilient tree varieties and strategically planted them in flood-prone areas. Within just a year of planting trees, these communities are already seeing improvements in flood control and water quality in their watersheds.

An expanded tree canopy also helps reduce the urban “heat island” effect, decreasing energy demand for cooling and thereby lowering carbon emissions from power plants. Emphasizing the myriad benefits of urban forestry, Lenoch explains that “you can use manmade structures and surfaces to get the same cooling effects of trees. But they don’t provide wildlife habitat like trees do. They don’t reduce traffic speeds like trees do. They don’t provide the other public health benefits that trees provide, like improved mental and physical health. That’s the best part of trees as a climate solution.”

While urban forestry can be seen as a silver bullet, Lenoch warns that “you can’t just plant any tree anywhere and leave it and expect it to have all these co-benefits. You have to plan what you plant and where you plant it. You have to have a maintenance plan for the life of the tree. You have to have a replacement plan in case the tree dies. You have to work with community members and neighborhood residents. Urban forestry projects are not just about planting more trees. There’s more that goes into it over the long term.”

While all these elements add up to long-term investment, the many benefits that trees provide—from carbon sequestration to reduced energy demands to improved water quality to elevated public health—make the effort worthwhile. As Lenoch says, “Trees are a vital tool for the health of all Wisconsin communities.”

• • •

Agriculture is one of Wisconsin’s leading industries, as the state is home to over 13 million acres of farmland. According to Fred Clark, Executive Director of Wisconsin’s Green Fire, “whether farms serve as a net carbon source or a net carbon sink depends largely on cropping methods, farm operations, and nutrient inputs.” Clark says that Wisconsin’s farm acreage is mainly managed through practices that emit, rather than store, carbon. This means we are missing out on a huge opportunity to leverage natural climate solutions in the fight against climate change.

As a conglomeration of minerals, living microbes, and plant matter, soil has the inherent capacity to store carbon. Different agricultural management systems can damage or enhance this capacity. Practices common among large-scale conventional operations, such as intensive tillage and the application of broad-spectrum agrochemicals, can damage the natural carbon storage capacity of soil. These operations often emit significant greenhouse gases through use of fossil fuel-burning equipment and other energy-intensive practices. By and large, these kinds of operations are net carbon sources.

By contrast, net carbon sinks are agricultural operations that minimize soil disturbance through targeted weeding, rather than wholesale tillage, and use of nutrient-fixing crops to keep soil covered in order to enhance the natural capacity of soil to maintain fertility and store carbon.

Imagine if we could leverage more of Wisconsin’s vast agricultural acreage into a giant carbon sink. Diane Mayerfeld, Senior Outreach Specialist at UW–Madison’s Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems, says that “there are many ways to improve the climate footprint of agriculture.”

One especially promising new practice for climate-focused farming is perennial agriculture. Mayerfeld notes that, for the most part, “all of our major staple grain crops, including corn, wheat, barley, and rye … grow for half of the year. During the other half of the year, the soil is bare.” On the whole, this type of agricultural system—spring planting, fall harvest—tends to emit carbon and leave soil vulnerable to carbon loss through erosion and respiration (free interaction of organic material with the air) during the intervening months.

Across the Midwest, farmers and researchers are working together to breed a robust spectrum of climate-resilient, perennial grain crops that could live through a whole year or more and be harvested multiple times before they die. These range from familiar crops such as grasses, wheat, sorghum, and various legumes to new crops like Kernza, a relative of annual wheat. According to Mayerfeld, perennial crops such as these can sequester carbon “as soon as it warms up, instead of just for a few months of the year. At the same time, they keep the soil covered, so it’s less prone to carbon loss.” While many of these varieties need to be further refined before they are ready for broad-scale application, Mayerfeld says they show “great promise for setting a more sustainable course for our global agricultural systems.”

Beyond their potential for capturing carbon, diversified agricultural systems can also provide a variety of economic opportunities. Mayerfeld tells the story of a Wisconsin farmer who returned to his parents’ conventional dairy farm and is in the process of transforming their operation to an all-perennial grass farm to raise grass-fed beef, sheep, and pastured poultry and pork. The farmer practices rotational grazing and has also planted fruit trees that provide shade for his animals and additional carbon-capture capacity. His integrated approach to farming reflects an emerging practice known as silvopasture in which the management of trees for timber or fruit is integrated with the production of pastured livestock and their forage.

This type of diversified agriculture especially makes sense for Wisconsin when you consider the history of our lands. “We had huge amounts of carbon stored in soil beneath our diverse prairie systems. Over 8,000 years, our grasslands—which co-evolved with ruminants (like bison)—were responsible for building up the deep, carbon-rich soils” that make Wisconsin so well suited for agriculture, Mayerfeld says. Shifting to agricultural systems that more closely reflect this history is an exciting new development that holds great potential for healthier farms and a cleaner planet. While this effort is still in its early stages, Mayerfeld is enthusiastic: “We want to make this shift in a big way.”

• • •

Totaling over 14 million acres, Wisconsin’s forests represent a significant carbon sink for our state. Current management of these forests is intended to balance a variety of needs, from animal habitat to recreation to timber harvesting. However, most management plans don’t explicitly consider carbon storage.

Managing forests for carbon storage can include a variety of practices: extending the time between tree harvests, thinning trees to ensure that the healthiest ones can thrive, and selecting species that are well-suited for a given planting location and hardy to the effects of climate change and pests like the emerald ash borer. Including these kinds of practices in forest management—along with statewide efforts in reforestation and afforestation (planting trees in previously un-forested areas)—could dramatically increase carbon storage potential for Wisconsin.

Of course, these natural climate solutions are more effective when implemented on more acres. Fred Clark describes how a program called My Wisconsin Woods powerfully leverages this concept. A partnership between the Aldo Leopold Foundation, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, and several other entities, My Wisconsin Woods provides private forest owners across the state with resources and technical assistance to engage in meaningful forest stewardship.

While some programs specifically work with large, institutional landholders of 100,000 acres or more, My Wisconsin Woods primarily works with families who own smaller forested acreages. This group of owners “makes up the majority of forest ownership in the state collectively,” according to Clark. Yet, he notes, “they’re also the hardest audience to reach and work with [because] many family forest owners are absentee owners who only visit their land occasionally.” Too, there’s frequent turnover. “On average, every seven years a family forest parcel is either sold or transferred to a new family member.”

My Wisconsin Woods uses social media, marketing, and other tools to provide information to new and long-time forest owners and get them more engaged in forest stewardship. The program provides information on everything from wildlife management to climate change to invasive species management—all the various facets that Clark says are important for considering forest health and productivity. By deploying tailored tactics for different kinds of landowners and speaking to a variety of possible motivations that family forest owners may have, My Wisconsin Woods has been highly successful in “creating a critical mass for landscape-scale impact” on climate change.

This kind of widespread, active engagement in forest management is becoming increasingly important, Clark says, because “we know that forests are one of our best sinks for carbon in the U.S. and in the world. … But forests are also under stress because of droughts, floods, and other impacts of climate change like increased introduction of invasive species. More than ever, people who care about forests are recognizing that we need to be active stewards. There are fewer and fewer cases where we can leave forests to their own devices and assume they’ll get better.”

However, effective stewardship can be a lot of work for forest owners. “The art is to try to balance their many goals in a way that is affordable and best meets the individual needs of forest owners so they’re willing to stay in the stewardship game,” says Clark. Whether you are a family forest owner who uses your land for recreation or growing timber—or both—chances are you already have some kind of plan to manage your forest. “We keep stacking needs and goals onto our forests,” says Clark, “and the need for our forests to help solve our climate problem is one more goal that we increasingly need to consider, and that forest owners are starting to consider.”

• • •

From the first forms of algae in our ancient oceans to the perennial grasses and fast-growing trees of today, nature has always found myriad ways to manage carbon in our atmosphere. Yet our planet’s innate capacity for handling carbon has been overwhelmed over the past hundred years by the rapid emission of greenhouse gases from burning fossil fuels. There are well–known and effective ways to curb these emissions, from reducing our personal energy consumption to employing renewable technologies like wind and solar power. However, natural climate solutions offer a unique opportunity for us to take advantage of our abundance of productive land, soil, and water in Wisconsin to capture the carbon that is already out there. Combined with major emissions reductions and a massive implementation of renewable energy projects, natural climate solutions can greatly accelerate our progress toward a cleaner, greener future.