Michael Perry is upset. The county highway commission wants to reconfigure the patch of road near his house, making it impossible for cars to climb the hill to his home in the winter. His neighbor Tom Hartwig, a feisty octogenarian with a “ye olde curiosity workshop” and a fondness for Civil War cannons, fought a similar battle decades earlier over the interstate that left his home forever in the shadow of rumbling traffic. His dignity in the face of an ultimately losing battle inspires Perry to action and reflection.

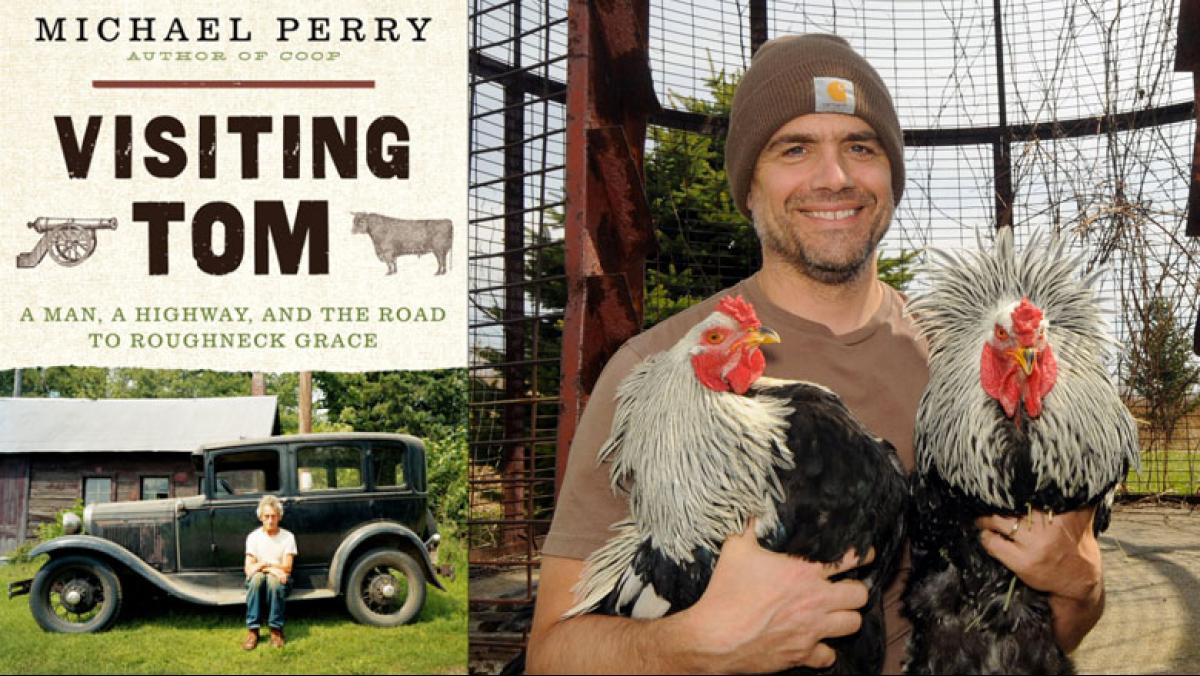

On its surface, Visiting Tom: A Man, A Highway, and the Road to Roughneck Grace sounds like a clunker of a story. Man fights bureaucracy, visits his eccentric neighbor, and learns life lessons. And in the hands of someone less observant, empathetic, and even less fretful and anxious, it would be. But Perry mostly pulls it off in a book that is part memoir, part character study, and a fine chronicle of rural life in modern Wisconsin.

Tom grew up on his land. It’s where he was born, brought his wife, raised his kids, and made a living. Everyone knows Tom. His fix-it skills are renowned. Perry memorably describes Tom’s workshop as “an antique store stocked by Rube Goldberg, curated by Hunter Thompson, and rearranged by a small earthquake.” Among the contents are wrenches, screwdrivers, a steel-rail engine hoist, and three cannons. Notorious do-it-yourselfers, Perry and his family find Tom and his workshop irresistible.

Visiting Tom has three main narrative threads: Tom’s recollections of his life and the construction of the highway; Perry’s own polite battle with government officials; and the ups and downs of family, fatherhood, marriage, and work. Much of Tom is revealed (both literally and figuratively) through the lens of Wisconsin photographers John Shimon and Julie Lindemann, who Perry hires to take pictures. It’s not clear at first what’s happening. The descriptions of the photography sessions appear in italics at the beginning of each chapter without explanation. Only gradually do the scene and Perry’s plot device come into focus. “Inch by inch the photographers cover the shop,” advancing slowly because Tom has a story for “every step of the way.” As they set up and frame shots, Tom tells some of his most affecting tales, augmented with a single and often stark photograph of Tom in his workshop, on the farm, and with his wife of sixty years, Arlene.

Perry doesn’t go to Tom with the intent of seeking advice. But the neighborly hours they spend together eating dinner, chopping wood, collecting honey, and bending rebar inevitably lead to conversations, stories, and small talk. Perry doesn’t canonize Tom, but rather reflects on his own life as he learns more about Tom’s. Both are husbands and fathers of daughters. Both love the land, their community, and value history. In his visits with Tom, Perry wrestles with complex issues: the struggle to be a good parent and partner; when to take a stand; how to balance work and family. “I don’t know if Tom Hartwig can make me a better dad,” Perry writes. “That’s incumbent upon me, not him.” But in Tom’s life, Perry clearly wants us to see the value of hard work, loyalty, grace, and self-reliance.

Some of the most touching moments in the book concern Perry’s two daughters. The eldest, Amy, is a stepdaughter but Perry refuses to describe her as such. “My standard line has become that the term stepdaughter is perfectly sufficient for conveying the situation, but utterly insufficient in conveying the heart, and above all I prefer the term lent me by a roughneck poet friend: my given daughter.” Amy’s presence and personality in the book, though modest, serve as cipher to Perry’s heart and contemporary family dynamics.

In the end, Perry and Tom come to have parallel stories in their fight over a road. Each man believes that what the government calls progress and improvement takes no account of its true cost to the land and people. This is the story on the ground. Above this, though, Perry’s overriding message is one of respect for the values, customs, and traditions of the past: that modernity does not by necessity mean discarding what came before.

Visiting Tom is not perfect. It ambles and wanders, and ventures a bit too far into the sentimental at times. Perry acknowledges this sappy aspect of his character, even calling himself “maudlin” at one point, but he barrels on anyway. His evocation of the past and deference to old ways of doing things occasionally feels suffocating in its reverence. But Perry’s humor, vivid observations, and turns of phrase—“It is one thing to be a work in progress; quite another to be a work in regress. Familiarity is no excuse for lowering your standards. Or so I said to myself last week while standing saggily before the bathroom mirror in my holey underwear.”—help to overcome the plodding points in a story that is as sweet as it is wise and eloquent.