After writing Studying Wisconsin, a biography of Increase Lapham co-authored with Paul Hayes, Martha Bergland was looking for another Wisconsin scientist whose life and work deserved more attention. She learned of Thure Kumlien in a poem by Lorine Niedecker, who, like Kumlien, lived most of her life near Lake Koshkonong. Research in the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives convinced Bergland that she had found her subject.

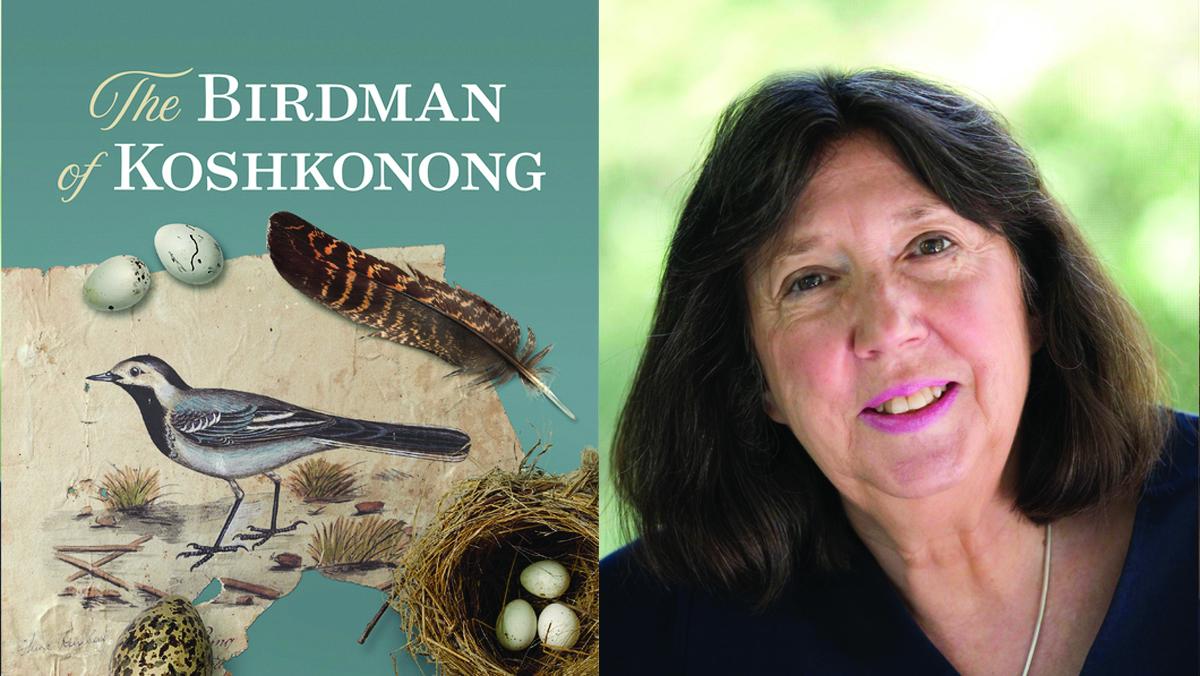

In 1843, Thure Kumlien, son of an aristocratic family, left Sweden and came to Wisconsin where he and his wife built a cabin at Lake Koshkonong. A naturalist, he preferred a quiet life in the woods and chose for his farmstead a place rich in bird life and virgin vegetation. What he accomplished from this beautiful and then remote location merits the attention it receives in Bergland’s well-researched and beautifully written biography, The Birdman of Koshkonong: The Life of Naturalist Thure Kumlien.

Bergland documents Kumlien’s lifelong dedication to fieldwork that advanced scientific knowledge of Wisconsin plant and animal species, the simplicity of his personal lifestyle, his love of beauty, his gentle and poetic spirit, and his care for the land. He maintained a section of his forty acres in their original wooded state, never clearing or plowing there. He also refrained from disturbing twenty-seven indigenous effigy mounds that are still intact today.

As she makes the case for Kumlien’s contributions to ornithology and his extraordinary character, Bergland also describes life in the new state of Wisconsin and the changes to the environment resulting from damming rivers and breaking up prairie into farm and grazing land.

Unlike Lapham who wrote extensively, Kumlien wrote only two papers for publication, one of them for the proceedings of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, of which he was a member. Kumlien’s early letters and his 1843-1850 work journal, a key source, were mostly written in Swedish. He did, however, speak and write English, as well as several European languages, and exchanged hundreds of letters with other naturalists. Bergland discovered that “the facts of Kumlien’s early life can be put in a tea cup.” Even so, she concluded that his Swedish background and education are key to understanding not only Kumlien the scientist, but also Kumlien the person who required of life “beauty, discovery, and knowing.” One of the beauties of Bergland’s book is the inclusion of Kumlien’s fine drawings of the birds he studied.

Kumlien studied at Uppsala University where Carl Linnaeus had established a system of taxonomy of plants and animals that is still the standard today. Even before he graduated, young Kumlien was sharing his knowledge and specimens with scientists in Europe and America. With these impressive academic credentials he began his work in Wisconsin collecting the bird, insect, and plant specimens that formed the essential collections of major museums and universities.

His was a well-rounded education with an emphasis on music, poetry, and Romantic ideas including the view that everything in the natural world has a soul. Bergland speculates that “perhaps more than anything else, it was Kumlien’s knowledge of Romantic literature and ideas that later separated him from the farmers who surrounded him in Wisconsin, with their hard-nosed practicality.”

Perhaps Kumlien could have benefitted from more of that practicality. His letters to those who bought specimens from him show a reluctance to discuss how he would be compensated for his work. Bergland does not venture into a consideration of whether his compensation was fair, though she certainly provides evidence of his poverty.

I could not help but wonder if this good man—whose keen observations and specimens from the field provided the means for better-positioned, better-compensated scholars to write books and advance their reputations—suffered from injustices in that system. Martha Bergland’s book at last brings Thure Kumlien’s life and work the attention it deserves.