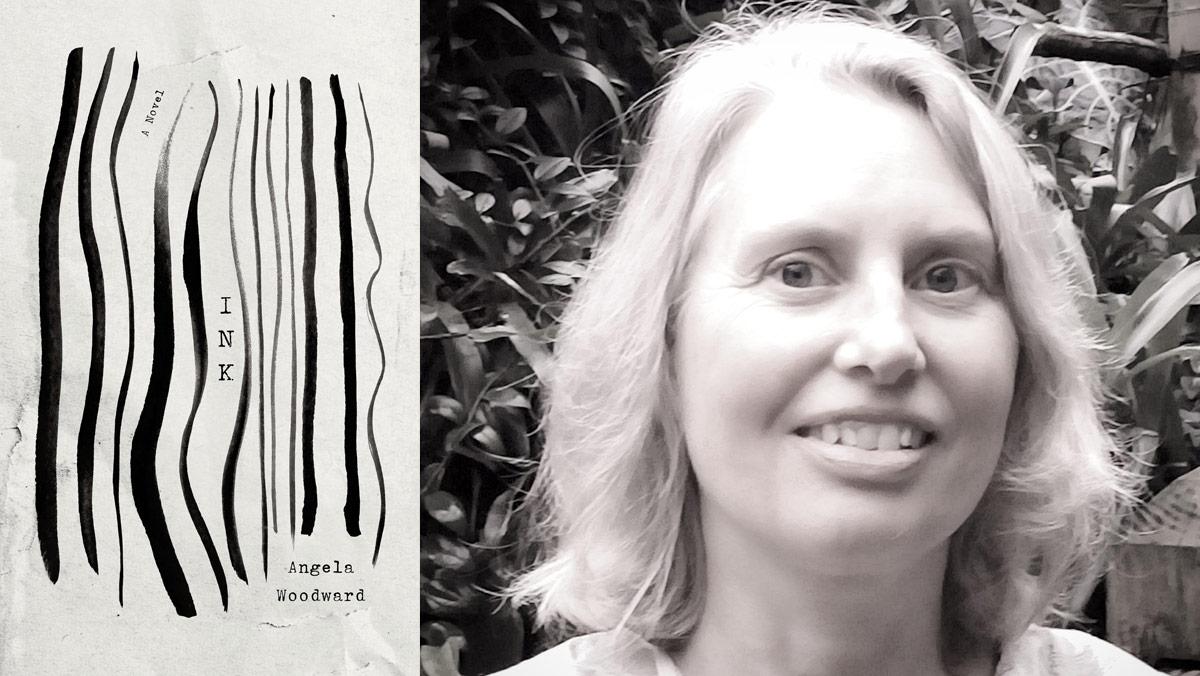

There can’t be many novels with titles shorter than the one that adorns Ink, Madison writer Angela Woodward’s third book of fiction; nor are there likely to be many novels in which short essays about the chemistry of ink (and the nature of other monosyllabic substances: ice, soap, blood) are interspersed in a story about two women transcribing accounts of Iraqi men and women tortured by American soldiers in Abu Ghraib prison in 2003. Ink is a novel determined to be different, like a piece of free-form jazz in which a talented musician/composer plays solos that sometimes point to common themes, sometimes seem like random if engrossing flourishes, and sometimes find a more conventional groove (such as those two women typists and their domestic lives).

We see the author herself in her house on the shore of Lake Monona, walking on the frozen lake, and in a waiting room editing a version of the book we are reading. Sometimes she chimes in with a self-critical note. “Needs connection,” she writes near the end of a riff about soap by the twentieth-century French poet Francis Ponge. A reader may hear in this memo-to-self an echo of advice found in E.M. Forster’s Howards End: “Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer.”

But Ink, like many texts of the last hundred years (see Finnegans Wake and the stories of Donald Barthelme and Lydia Davis), lives in fragments. The discrete (and fact-laden) pieces about ink and blood and soap and water flow (as James Joyce put it) via a “commodious vicus of recirculation,” into the offices of the Titan Corporation, where the two women, Sylvia and Marina, type the testimony of Abu Ghraib victims on ancient IBM Selectrics. The typists take little obvious interest in the subject matter of their work. The testimony functions as a refrain, thunder that shocks at first and then dulls with repetition. What mostly occupies Sylvia and Marina, who have between them three children and “zero husbands,” are, in addition to minor office issues involving soap and blood and ink, their lives outside the office.

It is in these domestic scenes, and especially in the moments between Sylvia and her teenaged son, Jordan, that Ink finds its fullest expression. Woodward writes about parent-child relationships with wit and tenderness. There is a fine scene in a formal wear rental store in a strip mall where the mother has taken her sullen son to get a suit for a choir concert. It is in this shop, as the son tries out a dance step in his rented jacket and Sylvia hides her tears, and at the concert itself, that “human love” is seen. Early in the novel, the author notes “how inevitable our failure [is] when we try to say what a thing [ink, soap, blood] is.” This slim book does not fail to show that soap is slippery and “ink obscures its nature,” and it succeeds as well in connecting the prose and the passion, exalting both.