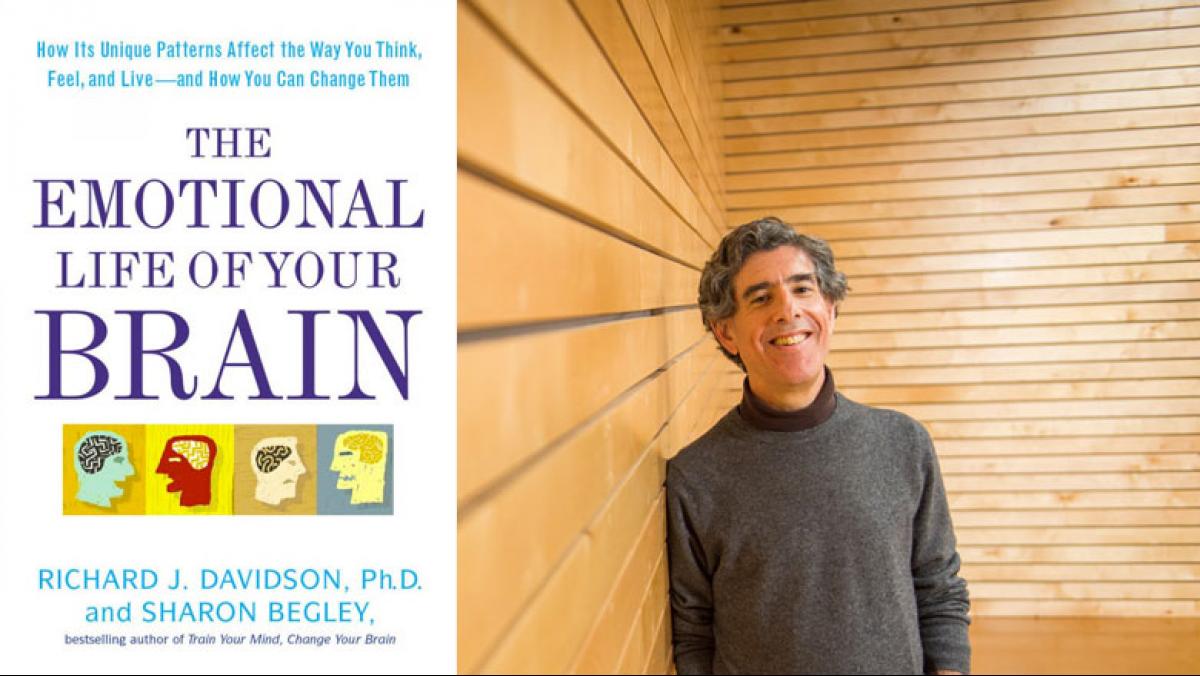

University of Wisconsin–Madison psychology professor Richard Davidson’s recent book, The Emotional Life of Your Brain: How Its Unique Patterns Affect the Way You Think, Feel, and Live—and How You Can Change Them (co-authored with veteran science writer Sharon Begley), is a wide-ranging summary of nearly forty years of research on the neural basis for emotion.

Equal parts research synthesis, self-help guide, and autobiographical tome, Davidson’s book makes a persuasive argument for the existence of Emotional Style, which he describes as “constellations of emotional reactions and coping responses that differ in kind, intensity and duration.” Composed of six primary characteristics— resilience, outlook, social intuition, self-awareness, sensitivity to context, and attention—Emotional Style ultimately governs the context and duration of our emotions, says Davidson, providing the underpinnings for that elusive element we know as personality.

This isn’t mere speculation or New Age hokum. Davidson is a world-class leader in the field of affective neuroscience, the study of the neurological basis for emotions. He made the Time Magazine list of 100 most influential people in the world in 2006, and in 2010 opened the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds (CIHM) in UW–Madison’s Waisman Center. Using state-of-art methods in cognitive, affective, and social neuroscience, along with modern biology, CIHM director Davidson works with an interdisciplinary team in translating how rigorous scientific research can best be used to nurture positive qualities of mind like kindness, compassion, and focused attention.

Indeed, The Emotional Life of Your Brain is in many ways a profile of the emerging field of affective neuroscience. Davidson begins by examining the tyranny of averages, that one-size-fits-all product of much health and psychology research and the take-away message it often seems to promote. The lingua franca of social science methodology, averages emphasize the vast majority of observations (e.g., the mean weight of American males is 190 pounds) at the expense of the few observations found in the tails of a distribution known as outliers.

According to Davidson, it’s these outliers—the extreme cases of psychological phenomena— that are perhaps more important to the process of explanation. By indicating direction and causality, outliers can be most informative in the search for scientific “truth.” Each of us can and does vary in Emotional Style—sometimes widely—and these individual differences can inform theory building, something Davidson demonstrates by examining autism, depression, and ADHD, and how these illnesses have neural correlates, i.e. how specific brain geography is statistically related to specific and extreme behaviors and emotions.

A central tenet of his thesis is the concept of neuroplasticity, a relatively new but well-established theory that the “brain is neither immutable nor static but continuously remodeled by the lives we lead.” Some of the strongest evidence of plasticity is compellingly demonstrated by people who have suffered from strokes or who are blind or deaf. These are cases—almost natural experiments—in which organic damage to certain brain areas has been measurably offset by a physical rewiring of other brain areas that pick up the neurological slack. In recent years, plasticity theory has largely overturned the prevailing orthodoxy that we are born with an immutable brain that is genetically endowed to be either healthy or diseased.

While a person’s brain and emotional style can change in response to experience, Davidson says that both can be changed—trained, if you will—by conscious effort, which can thereby improve a person’s life. This is a powerful and encouraging message in an era in which prescription drugs are viewed as a panacea for that which troubles us, emotionally or mentally.

One of the prescriptions Davidson offers to improve emotional style is meditation. In perhaps his most provocative research, Davidson is famous for studying a small number of Buddhist monks. His work in this area uncovered profound differences in not only the functioning of the monks’ brains but also how their brains are structured, suggesting the beneficial qualities of mind that meditation practice can cultivate. Far from being confined to monks, Davidson’s research illustrates that even meditation novices can produce demonstrable changes not only in their brain activity but also in their physical health.

Davidson lucidly presents the state of the art in a field that uses tools like electroencephalography (EEG) to measure brain electrical activity and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to examine changes in blood flow in the brain related to differential energy use. And the breadth of research cited—both his own and others—is impressive. Davidson recounts the evolution of his thinking on the brain basis of emotion by drawing on everything from research on anxious monkeys and young children’s interactions with robots to the brains of suicide victims and women who received Botox injections.

I found the most entertaining parts of the book in Davidson’s description of the serendipitous events that led to discovering how the brain produces emotion. His early research suggested that specific brain areas which were long thought to be purely concerned with cognition and reason—the so-called “higher” mental faculties— were also closely related to specific emotional patterns. Davidson relates the difficulty he faced in challenging the hegemony which held that emotions were not worthy of study. Yet he persevered in the face of skeptical advisors who cautioned that this course of inquiry was not the way to begin a promising academic career. In a chapter titled “Coming Out of the Closet” Davidson candidly discusses being a proponent of and active participant in meditation, and his attempts to gain broader acceptance—both personal and scientific—for a practice with measurable and quantifiable benefits.

The takeaway message of The Emotional Life of Your Brain, that we all hold the key to unlock a better emotional life for ourselves, reminded me of another book I have read numerous times over the years. Psychologist and philosopher Erich Fromm’s The Art of Loving, published in 1956 during the humanistic psychology movement, emphasized a very similar theme of love—what Davidson calls compassion— being a phenomenon worthy of rigorous study. Similar to Davidson’s book, The Art of Loving posits that far from being a mysterious feeling that does not submit to analysis, love is actually a skill that can be taught and developed through practice, responsibility, and knowledge. Unlike Fromm, Davidson proposes a practical means—namely, meditation—of actualizing these beneficial qualities.