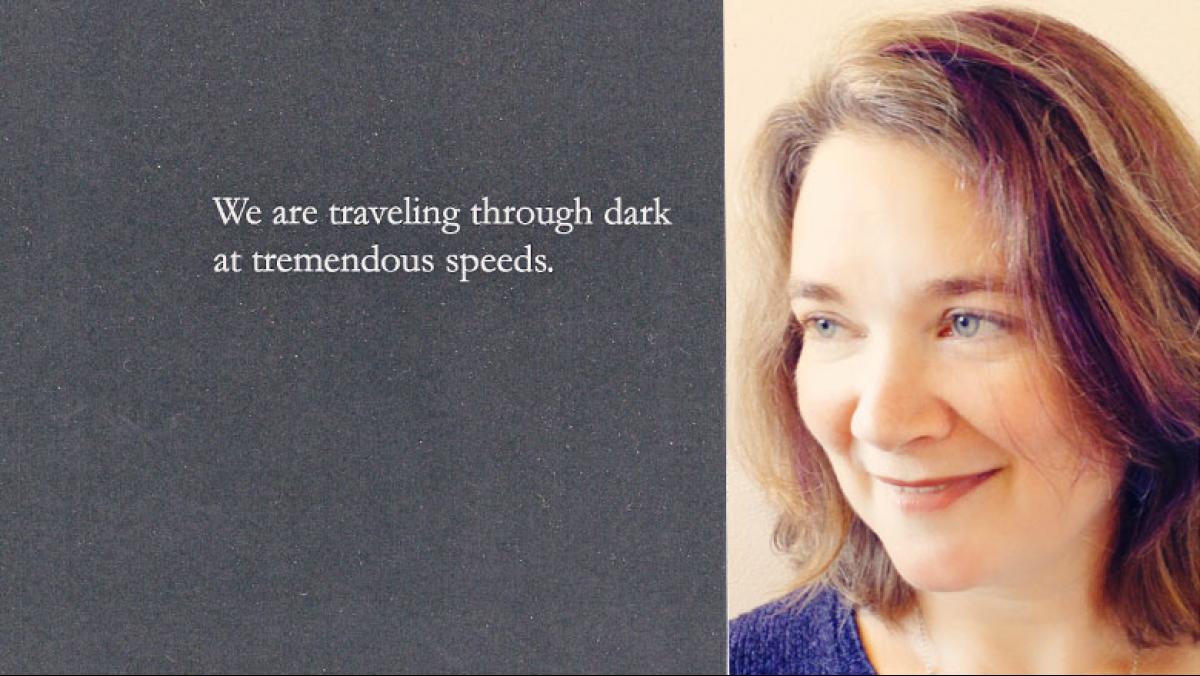

I’m one of those readers who start at the beginning of a volume of poems. I don’t page through, nor do I read the end of the book first. While reading Sarah Sadie’s new collection of poems, however, I found myself drawn to the narrative that scrolls across the bottom of the pages like a cable news ticker, adding additional depth and nuance the poems of We are traveling through dark at tremendous speeds.

Sarah Sadie is the nom de poem used by Sarah Sadie Busse of Middleton. A volume unlike most, this collection features poems and reflections about becoming, about defining and refining the self as (not?) Middle-aged, middle-class, middle-western. Flyover territory. The scrolling ticker at the bottom of the page continues, How can she paint a self-portrait. How can she paint anything but. I’m changing my name, she tells her husband. What’s changed? he asks.

Sadie refines and redefines the narrator and the notion of poetry through language that seems to draw from the Hélène Cixous essay, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” in which Cixous posits that women’s writing—even language itself—is part of a phallocentric world where women have no access to their own stories. In short, she has no body, is nobody. Cixous suggests that a woman must “write her self” to find her self. Busse as Sarah Sadie has created a persona that allows her to write as who she may be, may become. I created a space for her to emerge, and then she created me, a disembodied quote tells us at the beginning of chapter 2.

This feeling of otherness is enhanced by the book’s simple black cover with only the title announcing itself, no author name, nothing to name what’s inside, no page numbers. The back cover, the title in mirrored reverse, amplified by the forest of black lines that is the UPC code. Perhaps this is the book she mentions in “Riff on the Definition of Poem”

A book is a basket of deaths. Small ones.

A web with no spider (hide

her), this is the secret dilation …

Sadie challenges the middle ground of common experience with stylistic choices that disrupt the typical poetry experience. Her poems are right justified, and section separations do not announce theme or guiding premise, but are part of a continuing narrative. In fact, the entire volume is a continuing narrative. The ticker across the bottom is arranged to not only make its own meaning, but also to enhance what comes before. Sometimes it’s right to resist the flow, the go go go.

As I read I’m reminded of a book I read in graduate school, Borderlands: La Frontera, by Gloria Anzaldúa, in which the author (this is over-simplification and shaky memory at work here) suggests that for cultures to truly understand one another, we must not simply cross borders but create a space to live within the border. Inside that space is where we find something new, frightening, perhaps; but perhaps wonderful. Sadie’s poems live in these spaces, grow and thrive inside of what is known and what is newly discovered.

Within the borders of these two black covers is a woman, a poet, a mother, a wife, a teacher, all of her trying to create something meaningful. The narrator is a woman who has stepped across the border, a place in which she can create and/or reside.

… This is

the walled garden, the invitation,

an intimate penetration.

Let’s not lie or cover over.

It’s sexy as hell, what’s going on here.

—from “Riff on the Definition of a Poem”

In these pages we discover a woman finding her way through or to her new normal, her becoming. These are poems of a domestic exterior life—though Sadie is no domestic diva; she freely admits her frustrations—set against a private interior life rife with questions. Where are we again? How did we get here? Where is the exit?

To call Sarah Sadie’s book delightful wouldn’t do it justice. Thoughtful—requiring thought, perhaps. Wise. Or startling (where to start?). Wonderful or full of wonder. You decide, but let words, meaning, the familiar strangeness work their magic.

Start at the start with this volume, and whether you read the poems first, the crawling narrative second or in any order of your choosing, let these poems resonate—which is what good poetry should do. Notice how words and images thread and move in ways both artful and unexpected. Words can be an act of creation. Understand her exhortation: We are far beyond nouns.