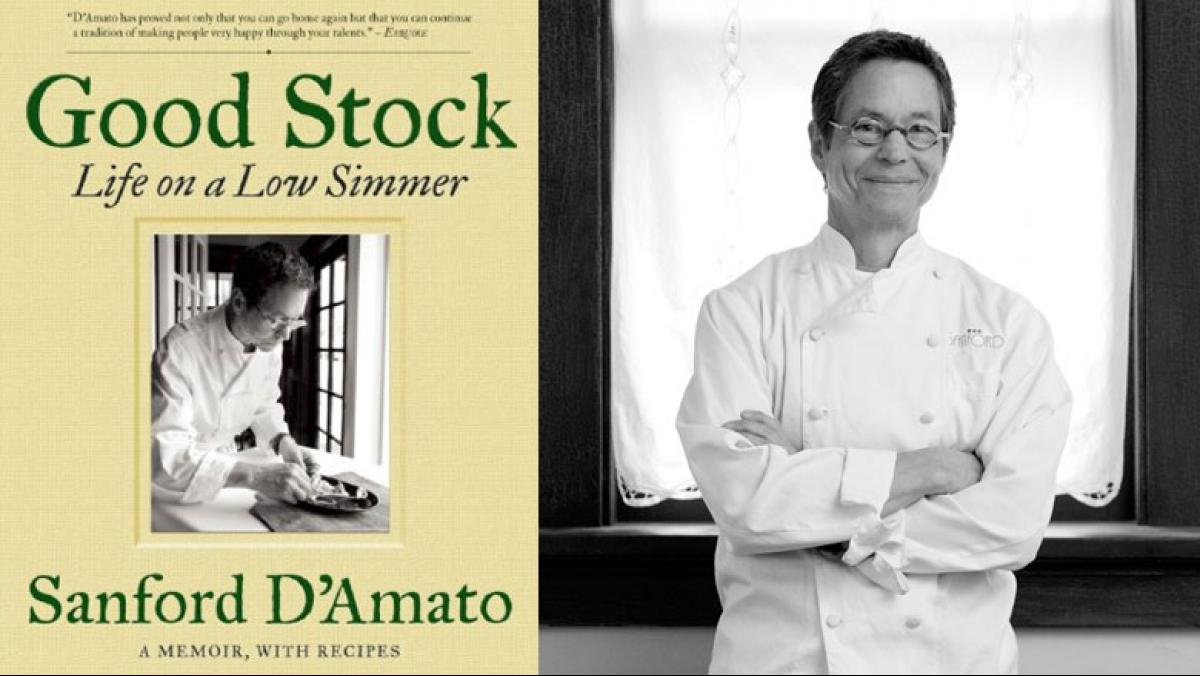

Good Stock: Life on a Low Simmer (Agate Midway, 2013) is an apt title for the new memoir—with recipes—by Milwaukee chef Sanford D’Amato. Good stock means bones, in both a literal and figurative sense: what we’re made of, the structure that shapes us, but also our family, our cultural heritage, our friends and mentors, even the city where we are born and raised.

What Wisconsin bec fin or gourmet hasn’t heard of Sanford D’Amato, winner of the James Beard Foundation’s Award for Best Chef: Midwest in 1996? D’Amato is a hometown boy who made good in New York before returning to Milwaukee to eventually open his eponymous lower east-side restaurant on the very same spot where both his father and grandfather had operated the family grocery store. It was terra firma, and something more—what D’Amato calls “the social center of a universe” in a neighborhood where everyone knew each other.

We learn in Good Stock that D’Amato’s love of food began some sixty-plus years ago on North Jackson Street, where his tastes were influenced not just by his dad’s Sicilian and mom’s German-English roots, but also by the city’s culture. D’Amato’s book recounts sentimental stories of family dinners (along with recipes for his grandfather’s spiedini—small beef roll-ups—as well as a take on his mother’s Schaum torte). But just as strong are his memories of Carvel’s soft-serve cones and burgers at the Butter Bun on Wisconsin Avenue or Big Boy at Wisconsin and Fifth Street.

In some ways, Good Stock is a nostalgic cook’s tour of the town. But the meat of the memoir—the making of the chef—comes when D’Amato leaves Milwaukee. He trains at the famed Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York, and is mentored by chef Peter Von Erp, one of the institute’s gifted and predictably exacting instructors. The account of their venture into Manhattan’s Chinatown is a delight, as are other stories of D’Amato’s ethnic food education.

D’Amato tells of cutting his teeth in several establishments, including New York City’s Le Veau D’Or and top-notch Le Chantilly. In a French-restaurant universe, where most of the employees in the 1970s were Frenchmen, D’Amato was a trailblazer, one of the first Americans to crack the Gallic ceiling.

But D’Amato’s life was far from charmed. And, like any good memoir, he details the ups and downs, both in and out of the kitchen. D’Amato doesn’t shy away from relating personal details—his failed first marriage, periods of unemployment, stints in places that flounder or that don’t deserve him. These experiences don’t break him. Rather they broaden his palate, reorient and teach him how to cook dishes true to himself.

Back in Milwaukee is where D’Amato solidifies his career, first as chef at John Byron’s, then on his own, opening Sanford in 1989 with his new wife Angie, who manages the books and the front of the house. A second restaurant is born, Coquette Café (also under new management since 2010), and a patisserie café, Harlequin Bakery (which closed in 2009).

And the world soon comes to him: a loyal following of food-lovers, a visit from Julia Child (she toured Wisconsin in 1990 and D’Amato cooked for her 80th birthday party in 1992), invitations to guest-chef, meetings with other award-winning cooks, an introduction to the Dalai Lama.

Looking back, D’Amato reflects on what has been a paced, well-lived life, as well as some of the lessons he has learned along the way—compassion, love, humility. It’s a powerful message, delivered with grace.

“A good menu should be a roadmap of your overall odyssey, with no end in sight. Your food should tell a story,” D’Amato writes. And he lets his food do the talking in over one hundred recipes, complete with lovely full-color photographs by Kevin Miyazaki.

Fans of his restaurants will appreciate D’Amato’s signature dishes, such as Grilled Pear and Roquefort Tart and Provincial Fish Soup with Rouille. But straightforward and down-home recipes like Bittersweet Chocolate Chip Pecan Cookies or Triple-Decker Burger are few and far between, leaving only a handful of options for the casual cook.

While the memoir’s anecdotal style might please some people, it can sometimes make for disjointed reading. And there are a few outright errors, such as when D’Amato refers incorrectly to an eastern area of France, the Franche-Comté, as the Franc-Comtois.

But this is small potatoes in an otherwise delectable book.