Neighborhoods are quicksilver creations, constantly changing residents, borders, and even names. Take the neighborhoods of Milwaukee, for instance: one generation’s Sixth Ward is another’s Brewer’s Hill, a German enclave in one century becomes an African-American stronghold in the next.

All neighborhoods are changing neighborhoods. Always have been, always will be.

Anyone who spends a day driving around or even through Milwaukee can plainly see that the South Side is a different world from the East Side, the North and West Sides have disparate characters, and the Northwest Side is another territory entirely. Within these and several other composite districts, we find dozens of neighborhoods, communities such as Bay View, Layton Park, Pigsville, Washington Heights, Rufus King, Riverwest, and North Point.

With a population of almost 600,000, Milwaukee is a large city. But its neighborhoods render it both intelligible and approachable. While these neighborhoods come in many shapes, sizes, colors, and strengths, together they constitute the fundamental building blocks of the entire community.

In forty-plus years of studying my hometown, I’ve learned firsthand that every neighborhood has a story uniquely its own to tell. I firmly believe that telling their stories can encourage a sense of belonging within individual neighborhoods and a sense of mutual respect across neighborhood borders and even beyond the city limits. This is the impulse behind Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods, a new book that is, if only by default, the most complete chronicle of grassroots Milwaukee ever published.

Of course, the subject practically guarantees rapid obsolescence.

Rapid change is a natural condition of communities that exist not by force of law but by virtue of perception. We codify some lines to identify census tracts or legislative districts or municipalities, but neighborhood borders simply float in our shared awareness, perennially subject to both dispute and revision. Milwaukee doesn’t have a Minneapolis-style confederation of neighborhoods with borders set by the city council, and it never attracted anything resembling the corps of sociologists who delineated Chicago’s “community areas” in the 1920s. All that’s possible is an informed and reasonable but patently imperfect interpretation of where one neighborhood ends and another begins.

Not that there haven’t been attempts to draw hard lines in the shifting sands of residential Milwaukee. Over the last half-century or so, academics, urban planners, and community activists have made repeated runs at an “official” map of Milwaukee neighborhoods.

The most ambitious effort dates to the late 1980s, when the Department of City Development (DCD) launched its Neighborhood Identification Project. The project’s goal was “a stable set of neighborhood boundaries” that would become “a recognized

and engrained part of the fabric of the City in the future.” The Neighborhood Identification Project map was drafted with social uplift as well as consistent data sets in mind. “This will give every resident of Milwaukee,” promised the planners, “an opportunity to develop a sense of place, pride, and belonging in relation to where they live.”

The problem, if it may be so called, was that the project’s leaders were determined to put every square inch of the city in one named neighborhood or another, even when the lack of historical or organizational referents forced them to resort to whole cloth. My favorite fabrication was the area just east of the Allen-Bradley (Rockwell Automation) clock, which, presumably to the surprise of its residents, surfaced on the final map as “Clock Tower Acres.”

I was part of a similarly well-intentioned stab at the elusive geographic truth, again under City of Milwaukee auspices. In 1982 Greg Coenen, manager of communications for DCD, conceived the Discover Milwaukee Program in an earlier attempt to encourage a sense of citizen belonging. As the Discover Milwaukee Program writer and researcher, I chose most of the neighborhoods; others were suggested by Coenen or dictated by higher-ups in the department.

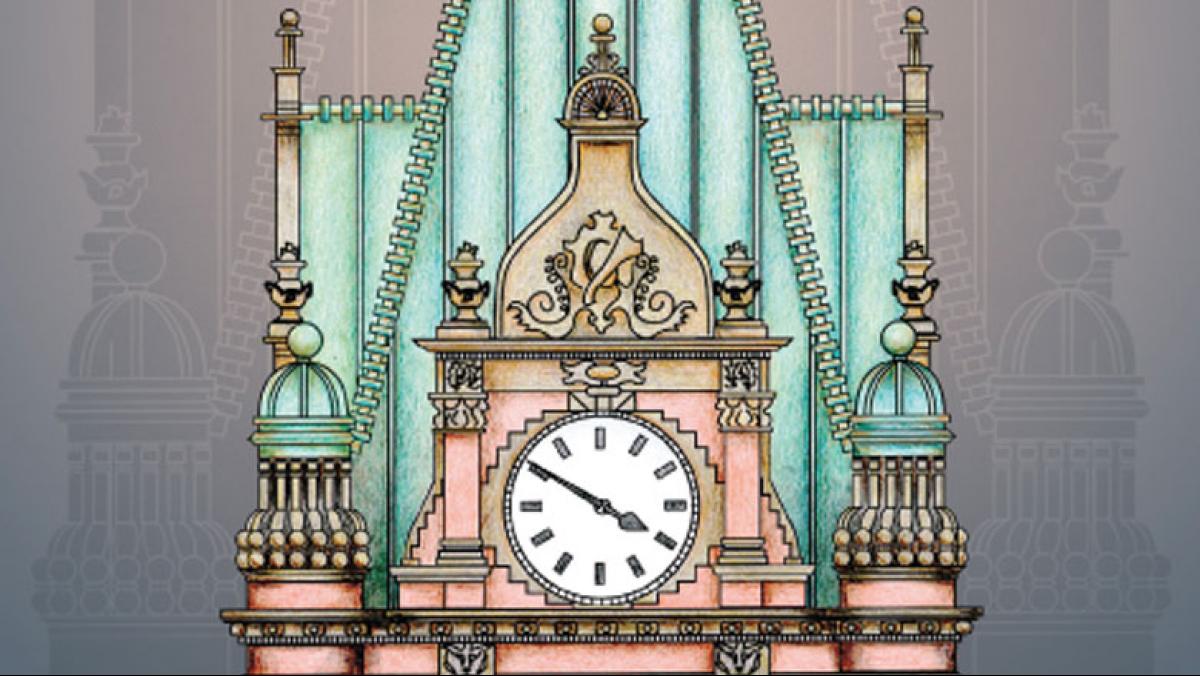

The program’s signature product was a series of twenty-seven posters painstakingly drawn by Janice Kotowicz, a DCD staff member with deep roots in the city. Kotowicz typically used a characteristic architectural feature for her illustration—a bungalow in Sherman Park, a Victorian storefront in Walker’s Point, a Polish flat in Riverwest—while I prepared magazine-length historical essays that appeared on the back of each poster. (My words were consigned to permanent oblivion if the art was ever hung for display.) The posters, which debuted in batches between 1983 and 1990, were hugely popular, showing up in corporate offices, TV interview rooms, public hallways, and thousands of private homes. They made Jan Kotowicz the most famous Milwaukee artist you’d never heard of.

Twenty years later, the posters were still in print and still in demand. In about 2010 I ran into Kotowicz at the South Shore Frolic in Bay View, the neighborhood we’ve both called home for many years, and she said, almost off-handedly, “We should turn those posters into a book.”

Thus, the idea for Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods was born.

The task had seemed relatively simple at first: update the original twenty-seven essays to reflect nearly three decades of change and then write perhaps a dozen new chapters on communities we never got to in the first round. The project evolved (as projects will) into something more complex: hundreds of miles of travel on foot and by bicycle, long days in local archives, and the constant struggle to hit a moving target so that the work seemed neither hopelessly anachronistic nor overly generic.

There were endless decisions to make, the first involving which neighborhoods to include. The roster is hardly exhaustive. In the interests of time, space, and sanity, I confined myself to the pre-World War II city, an area defined roughly by Silver Spring Drive, Howard Avenue, Sixtieth Street, and the lake. Profiles of most of the neighborhoods within these borders are legacies of Greg Coenen’s Discover Milwaukee Program; others I added based on a thoroughly unscientific blend of subdivision borders,

major geographic barriers, historic settlement patterns, and current organizational service areas.

The list could have been significantly longer, but it is in prewar Milwaukee that the historical layers are most abundant, the cultural currents most visible, and the stories most resonant—if only because they’ve been echoing for so long.

There are genuine neighborhoods beyond my chosen borders, including nineteenth-century nodes like Granville Station or New Coeln and historic subdivisions like Morgandale or Wedgewood Park. But the postwar city tends to be largely one piece: mile after mile of Cape Cods and then ranches and split-levels, punctuated by apartment corridors and commercial strips. Even in the older part of town, some areas are so diffuse (or so diminutive) that it’s difficult to classify them as neighborhoods. Rather than force the issue, I chose to leave a few blank spots on the map.

Choosing a graphic format was significantly easier. Kotowicz’s original poster illustrations, augmented by her eleven new creations, are the visual anchors of the book. These illustrations are complemented by customized maps and a generous assortment of both historic and contemporary photographs that help bring each neighborhood to life.

It took a while but, with the sponsorship of Historic Milwaukee Inc. and the generous support of more than a dozen community-minded funders, the book was published in September 2015. The result, we hope, is an appealing hybrid between a history book and an art book that will retain its relevance as a benchmark in precisely the same way that 1930s studies prepared by Works Progress Administration retain their value today.

Milwaukee, as much as any large city in America and more than most, is marked by painful inequities in both income and opportunity. But whether a specific neighborhood narrative has led to vibrancy or pathology is not really the issue here. City of Neighborhoods reflects the obvious reality that not every community is created equal.

Yet every story has intrinsic human value. Stories from Harambee are just as important as those from North Point; Metcalfe Park stories are as valuable as those of Bay View. Just as no understanding of the city—or of America—is truly complete without an understanding of the contrasts that define our society, no vision of a more hopeful future can emerge without a sure grasp of the past.

For me, it was an undiluted pleasure to make the acquaintance of my hometown at the neighborhood level once again: to bike, to chat, to question, to photograph, and simply to witness Milwaukeeans in the act of being Milwaukeeans. Yes, there’s been change and, yes, there are problems. But there is also an undeniable richness to life in Milwaukee. Chris Winters, our lead photographer, may have said it best: “The deeper you go in the neighborhoods, the deeper they are.”

It is my hope that Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods will help readers to discover some of that depth for themselves. There may be no more dynamic human creation than the city, no more compelling expression of energy, aspiration, pain, and potential on the planet. Neighborhoods are the parts that make up the larger organism; it is in seeing our neighborhoods that we see our city whole.

This piece adapted from Milwaukee: City of Neighborhoods, by John Gurda. Published 2015 by Historic Milwaukee Inc. Reprinted by permission of the author and publisher.