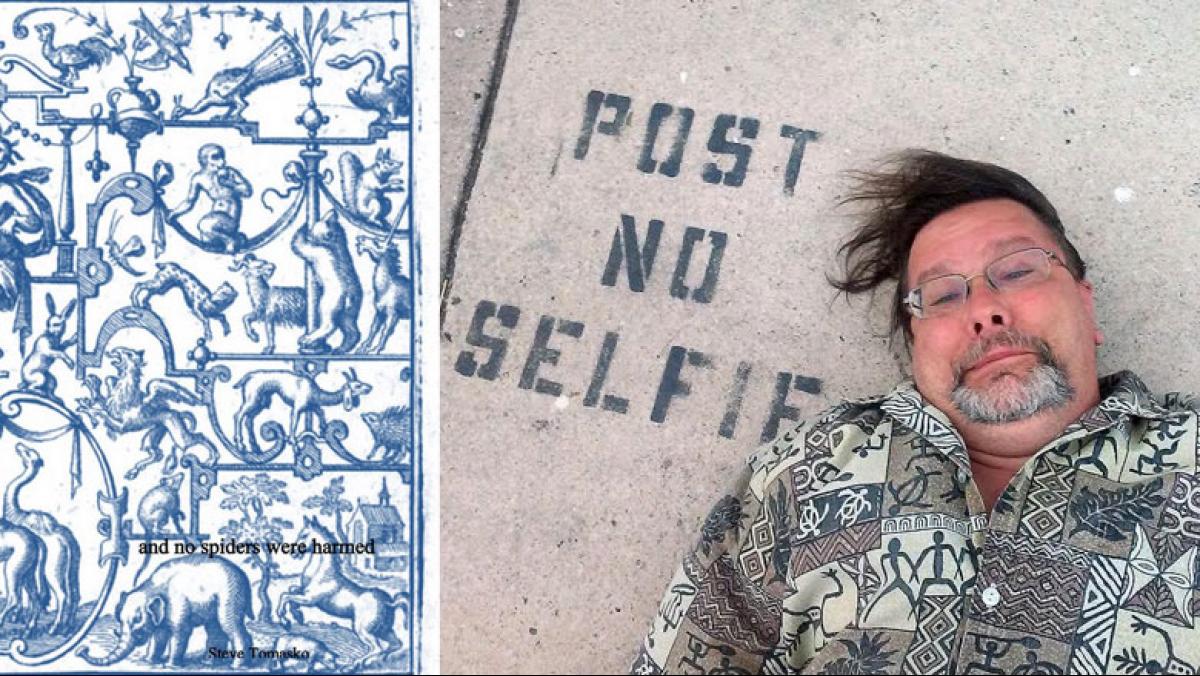

“You said I should write more love poems / and I said, I’m sorry, but I’ve been thinking about / sloths.” This is the opening gambit for and no spiders were harmed, Madison poet Steve Tomasko’s debut chapbook.

Some may think there are enough love poems; some may think there is need for more. Certainly, there is a need for more poems about sloths, ants, spiders, cicadas, “sparrows, crows, and moles.”

With the ears and heart of a poet, and the eyes and sensibilities of a scientist, Tomasko leads readers on a wonder-filled journey of what it’s like to be human, animal, and insect. Though filled with critters, these poems won’t give readers the heebie jeebies—unless you’re creeped out by spiders, which, the poet himself admits to be:

Sister Therese writes in a letter that she

has a spider on her pile of books,

wants to know if I ever wrote about them.

How to confess that I, who people call

bug man, get the willies around them.

There are a lot of spiders in this small book. Tomasko writes about spider silk collected to make wartime bomb-sight cross hairs and a golden, brocaded cape. In another poem, a bodhisattva spider shows up trying to teach the poet about being hooked in the lip like a caught fish.

Accessible without being predictable, these poems are more about love than insects. In one, the poet removes a toad, hibernating in a pot, which will surely die if left “well above the frost line.” In another, the poet kills and flushes a spider found in the corner of the bedroom ceiling; but the next night, he carries another in a Mason jar to the garden.

I did mention there are lots of spiders.

There is also dark humor—“Females who have mostly dispensed / with men,” or the female praying mantis who eats the head of the male while he’s mating with her. “And it’s not that he moves faster / without his head. / Well, actually, / that is the horrible thing.”

Tomasko uses the trope of non-human creatures to lead readers through the very human subject of grief, and how verb tenses can be tricky. Is one day, is was the next. He says, “The body hungers on despite the question of tense.”

Intimate without being sentimental—maybe that’s what love should be, not cloying expressions of sentiment—Tomasko’s world is a place where love can be found in the symbiotic relationship between two distinct species:

The algae-covered sloth fur is the only home

the sloth moths know. The only place they live.

I know it’s a Darwinian thing, but fidelity

comes to mind. Commitment. Patience.

The world writes love poems all the time.

Still, Tomasko’s wife Jeanne wishes he’d write more love poems.

Editor's Note: A version of this review appeared in The Boston Area Small Press and Poetry Scene Blog.