Melissa Range’s newest collection of poems, Scriptorium, brings together what seem to be disparate elements: medieval religious manuscripts, Old English literature, “hillbilly” stories from East Tennessee. They will come together—but you have to spend some time in this book, the title of which means “a place for writing” in Latin.

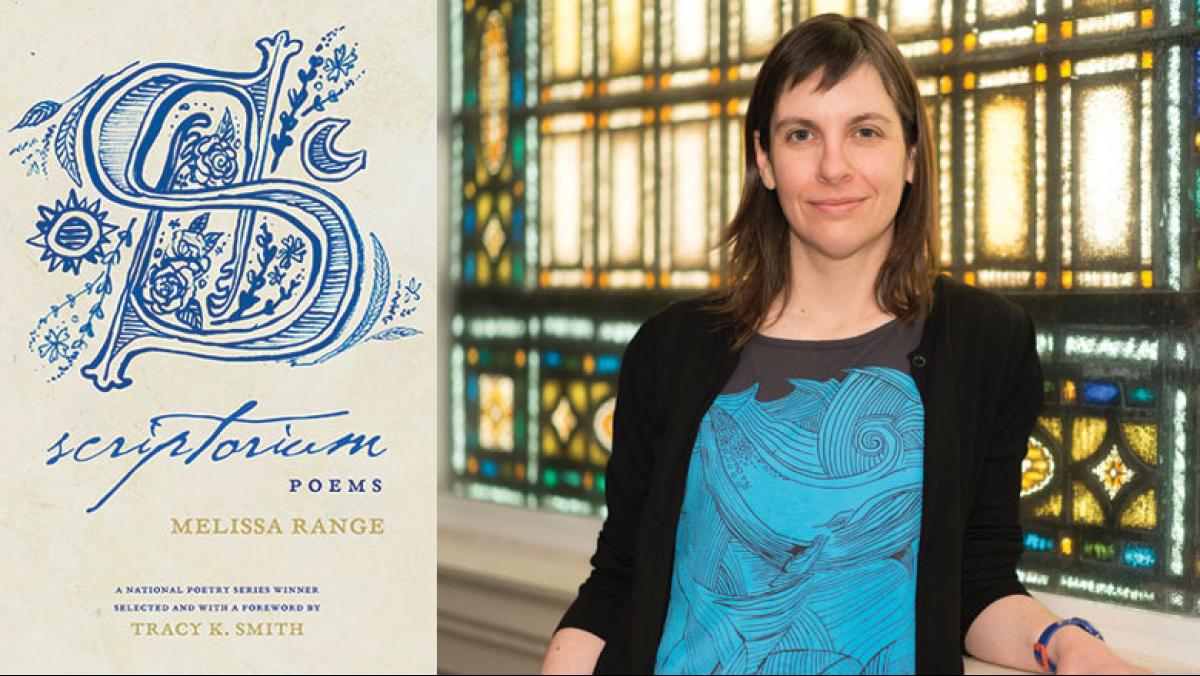

A 2015 National Poetry Series Winner and author of another collection, Horse and Rider (2010), Range teaches English at Lawrence University in Appleton. Her Scriptorium, which garnered her the 2015 award, is bursting with surprising language and imagery that flickers and flits from poem to poem.

Is this a monk mumbling over his pot of pigment, his brush bent? Or is it some celebrated hero of myth, explaining the ways of God? No, it’s a father in one of her Appalachian poems, “Flat as a Flitter,” fixing strip-mining equipment, “everything / to him an innocent machine in need.”

For a taste of Range’s talents, one need only look at her pigment poems, each named for a color compound used to decorate the kind of sacred manuscript one might find in a scriptorium: verdigris, Kermes red, Tyrian purple. “Lampblack” is an excellent example; each word calls for its own attention, so the end rhyme swirls within the mix of all the other sounds, a cacophony; each bit of language seems brand-new, burnished. It begs to be read aloud.

Black as a charred plum-stone, as a plume

from a bone-fire, as a flume of ravens

startled from a battle-tree—this lantern resin

the monk culls from soot to quill the doom

and glory of the Lord won’t fade.

Multiple layers of sound seem almost visible: “plume” rhymes with “doom” (as the form demands), but also echoes “plum” and “flume.” Look how “culls” and “quills” mock each other in line four: to cull means to select from a larger quantity; “quill” should more properly be “quell”—we want to quell doom—but here the color lampblack is in the quill, used to write. (Perhaps writing is how we quell doom.)

Range draws words from her world—wainscot, ofermod, Schlitz—to pepper these poems, many of which feature undulations of form, sound, and sense. These are tangles meant to be untangled. The key to understanding how this all works together—these colors and considerations of God and (un)belief, this history of growing up in East Tennessee where the dialect holds traces of Old English—may be found in the revelatory title poem, which comes near the end of the book.

Like any good story, a good collection of poems has its own narrative arc, building through its inciting event and complications to its climax and resolution. In “Scriptorium,” we meet Eadfrith, the Anglo-Saxon monk who illuminated (illustrated) the Lindisfarne Gospels, perhaps the first and greatest masterpiece of medieval European book painting. The poem describes Eadfrith gathering his materials for this masterpiece, and how “The earth, not the cell, / is his scriptorium.” The poet could be talking about herself, about all poets.