On a warm fall day in September 1973, James Batt watched as two plaques were affixed to the sandstone entryway of a small office building at 1922 University Avenue in Madison. The squat, cream-colored building was to be the first permanent home of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters, an over one-hundred-year-old organization dedicated to cultivating Wisconsin ideas.

Yet the new Academy headquarters was bit of an outlier on a street composed mainly of homes belonging to University of Wisconsin–Madison faculty and student-rented flats. Earlier, the space at 1922 University Avenue had housed an outpatient services clinic and, before that, doctors’ offices (which explained the small office suites within).

The plaques hung that warm September day recognized two significant gifts that allowed for the establishment of the new Academy offices. The one on top honored Elizabeth McCoy, a microbiologist and longtime editor of the Academy’s scholarly journal Transactions, for her generous donation toward remodeling the building’s interior. The plaque below christened the building as the “Steenbock Center” in honor of biochemist Harry Steenbock, who had bequeathed to the Academy an endowment to be used to purchase the building and fund the Academy’s future projects.

Batt, then in his second year as the Wisconsin Academy’s first full-time executive director, likely realized the weight of this historic moment. Until then, the Academy had been more of an association than a destination. Now that it had a permanent home, the Wisconsin Academy could even more forcefully realize the vision its founders had set forth over one hundred years before doors of the Steenbock Center would open for the first time.

Founded in 1870 by a group of the state’s leading citizens, the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters had for over a century worked to improve the condition of life in Wisconsin by sharing knowledge. Participation in this learned society was a way for members to share ideas with peers and advance their own knowledge, often through annual gatherings and scholarly publications. The Academy Council (today’s Academy Board) ran Academy operations in their spare time, juggling full-time jobs as educators, naturalists, and attorneys with work on the annual Transactions journal, member meetings, and other business.

All this changed in 1971 when the Steenbock Center was established and the Academy Board voted to hire Batt as executive director. Batt wanted to “breathe new life into the arts and letters” by expanding Academy membership, reaching more people, and developing more place-based programs that could better serve communities across the state. In Batt’s vision, the Steenbock Center would be the headquarters for new activities in Madison and around the state that would bring Academy members and the public together in search of innovations in—and conversations around—the sciences, arts, and letters.

Standing on the threshold of 1922 University Avenue, considering the people who made this vision possible, Batt no doubt felt a sense of trepidation. The Academy stood at the precipice of a new era, one whose future would build upon the strength and dedication of the past. There was, however, no guarantee that Batt and his colleagues would succeed in creating a thriving, self-sustaining organization. Like the founders who established the Wisconsin Academy just five years after the American Civil War ended, Batt and the Academy Board were entering largely unexplored territory.

For the Betterment of Wisconsin

When the Academy was founded in 1870, Wisconsin had been a state for only 22 years. With so much still unknown about its land, waters, and people, the intellectual atmosphere in Wisconsin was one of excitement and discovery. One of the Academy’s founders, geologist Thomas C. Chamberlin, described the “primitive wildness” that inspired curiosity in early Wisconsin scholars like him:

Out of the irresistible attractions of the native life of the air, the woodlands, the grove-encircled prairies, the meadows, the marshes, the limpid streams, and the charming lakes of Wisconsin, there grew the first notable stage of spontaneous scientific activity, the stage of the enthusiastic naturalist.

As Wisconsin’s early citizens cultivated the land for farming and settlement, they were eager to catalog and report their observations of this new environment. Meanwhile, scholars saw the need for a deeper and more organized investigation into what the varied soils, minerals, waterways, and forests of Wisconsin had to offer. An idea for creating a repository of information about Wisconsin that could be collected and drawn upon by citizens, not unlike the recently established National Academy of Sciences, began to take hold among a group of civic leaders.

John W. Hoyt, then the secretary of the State Agricultural Society and a scholar of law, medicine, and natural history, sent the first call to an academy meeting, inviting prominent citizens to an organizational convention in Madison. However, Hoyt and other founders weren’t content with merely an Academy of Sciences. Hoyt sought to enlist “all who are zealous for the advancement of science, art, and literature, in any one, or in all of their several departments” to engage in interdisciplinary exchange through the formation of the Academy. Hoyt suggested such a body undertake a “thorough and economical scientific survey of Wisconsin, embracing, not only its geology, but also its meteorology, botany, zoology, agriculture, and archeology.” The call to meeting was signed by 105 of Wisconsin’s most prominent citizens, and the organizational convention for the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters was scheduled for February 16, 1870 in the State Agricultural Rooms of the Capitol Building.

The call to meeting professed that such an academy would “largely contribute to the social progress of the State” by “awaken[ing] a scientific spirit in all inquiring minds and thus lead to a more fruitful intellectual activity among the people at large.” Hundreds of citizens attended the organizational convention, where they established the by-laws for the new organization. The Wisconsin state legislature chartered the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters on March 16, 1870.

In many ways, the Academy was ahead of its time. While scientific academies were common in the late nineteenth century, very few combined scientific research with an investigation of the arts and letters. Today, the Academy is one of only three such academies to do so. Furthermore, the Academy always affirmed that research should serve Wisconsin citizens, a concept that helped lay the foundation for the Wisconsin Idea.

While the phrase is attributed to University of Wisconsin President and Academy member Charles Van Hise, the Wisconsin Idea was described by Charles McCarthy in 1912 as the broad principle that scholarly work should benefit the citizens of the state. In his book The Wisconsin Idea, McCarthy named 46 citizens of his time whose lives reflected the principles of the Wisconsin Idea. More than half of them were Academy members.

Founding member Thomas C. Chamberlin reflected on the Academy’s founding and function at its 50th Anniversary celebration in 1920: "This coming together … of good men from all parts of the state to found an academy whose chief purpose was to facilitate a concerted search for truth for the common good, stands forth as an altogether signal event in the intellectual development of our people."

Chamberlin, who was early in his own career when the Academy formed, benefited greatly from his involvement in it. He went on to write one of the earliest papers on climate change, noting the connection between atmospheric carbon dioxide and the glacial period. In Chamberlin’s view, the Academy had become a force for good in Wisconsin.

Throughout those early decades, the Academy built a reputation as a learned society in which scholars could gather and share ideas. They presented their innovative research in papers read at the annual meetings. Many of these papers were then submitted for publication in the Academy’s Transactions, a scholarly journal that was produced continuously for over 130 years. A sample of these papers reveals a broad and deep swath of Wisconsin knowledge: assessments of Lakes Michigan and Superior commercial fisheries, descriptions of common folk songs, images of the crystal formations of snow, mineral analyses of Marinette’s artesian wells. Transactions was also part of a journal exchange program with research organizations across the globe, providing the Academy with an impressive library. This international journal collection has since been incorporated into the University of Wisconsin Libraries.

Through the efforts of geologists, zoologists, naturalists, and others who collected samples and specimens for display and study, the Academy successfully lobbied for, and later staffed, the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey. The survey was one of the Academy’s primary objectives, as delineated in the charter from the state. The formal establishment of the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey in 1897 was the Academy’s greatest early victory.

A Century of Service

The Academy’s early momentum launched over a century of steady, if quiet, work to advance knowledge in the sciences, arts, and letters. Though the Academy often lacked funds, it rarely lacked enthusiasm. Devoted scholars contributed what time and energy they could to the Academy, and made it a place to nurture scientific understandings and to share those understandings across disciplines. This became most obvious when the Academy started to expand into new endeavors. Often backed by a handful of enthusiastic members, new projects were often added to the Academy’s portfolio when opportunities arose.

One of these projects was the Junior Academy. Beginning in 1944, the Academy, in collaboration with the University of Wisconsin, began organizing science workshops and science fairs for high school students. Reflecting the pro-science sentiment of the post-World War II era, the new Junior Academy sought to engage students in scientific research and inspire curiosity. John W. Thomson was hired to run the project and was released from his teaching duties in the Botany Department for two years in order to develop program materials and recruit Junior Academy members.

Thanks to Thomson’s hard work, the Junior Academy grew quickly. In 1945, it hosted its first meeting, bringing together high school students to present their scientific research. By 1960, the Junior Academy was holding eight high school district meetings and six regional junior high school meetings at locations across the state several times per year. Junior Academy members with the best scientific papers were invited to present them at annual Wisconsin Academy meetings. A 1961 survey of Junior Academy participants revealed that 90% of them went on to pursue science in some form.

The Academy saw its Junior Academy as an opportunity to inculcate scientific principles and civic participation in students while laying the groundwork for their future participation in the organization as elected members. The Junior Academy eventually created its own annual publication, showcasing not only the original research of Wisconsin high schoolers, but their artwork and creative writing as well. The Junior Academy is but one of the many ways the Academy provided opportunity and encouragement for people with a desire to share their ideas.

In response to the popularity of the Junior Academy magazine, Walter Scott and his wife Trudi began publishing one for adult Academy members. The Wisconsin Academy Review had its debut in 1954 with an article on “The ‘Wisconsin Idea’ and the Academy” by University of Wisconsin president E.B. Fred and a survey of recent Wisconsin Archaeological Society projects by Milwaukee Public Museum director W.C. McKern. However, much of the magazine was dedicated to news about Academy members, such as awards received and recent publications, as well as summaries of Academy events and business activities.

The quarterly magazine was a pilot of sorts, intended to “build the Academy’s membership strength and increase its potential service to the state as a catalyst and clearinghouse for all worthy activities in the fields of sciences, arts, and letters.” Because the Academy had no office and no dedicated funds for the publication of Wisconsin Academy Review, design and layout was often done in the Scott home. Delivered to Academy members, the magazine often would be passed on to friends and colleagues. Indeed, the first issue encouraged over 35 new memberships. By 1957, the Review was credited with growing membership outside of Madison by 300% and increasing out-of-state membership in the Academy by half.

An expanding body of Academy members and growing public awareness of Academy programming also invited more input about the Academy’s agenda. “We must not merely be a study group,” exclaimed Academy Board President Aaron Ihde in 1963. Idhe, a renowned historian of chemistry, as well as other Academy members saw the benefits of growing the Academy into a more public-oriented body while also inviting more cross-disciplinary programming, especially in the arts and letters. None the less, dwindling financial resources and a lack of dedicated staff meant these Academy ambitions had to be set aside for much of the 1960s.

For decades the Academy had been able to do extraordinary things with very little funding. In his history of the Academy published in Transactions (1962), wildlife management pioneer and Academy Board President Arlie Schorger noted that “it is doubtful [that] any other Wisconsin organization has accomplished so much at so little cost to its citizens.” However, time seemed to be running out for the Academy to take a bold next step into a new era of public programming.

The Dawn of a New Era

Fortunately, near the end of the Academy’s first one hundred years, the dedication and hard work of its members received a huge boost. Years before, University of Wisconsin biochemist Harry Steenbock had discovered that the ultraviolet radiation of food could increase its level of Vitamin D—a vitamin essential in the prevention of a serious bone disease called rickets. Steenbock patented the process and left a large portion of his accumulated royalties—nearly $1,000,000—to the Wisconsin Academy when he died in 1967. Steenbock’s bequest allowed the Academy to consider a future where free and low-cost programming could spread ideas and innovations to a much broader—and most importantly, non-academic—audience.

In 1971, the Academy purchased the Steenbock Center and started its search for an executive director—the first full-time staff member for the Academy—to lead the organization forward into the new era. Batt had been serving as assistant director for Academic Programming at the Coordinating Council for Higher Education. Louis Busse, who was Academy Board President at the time, was charged with recruiting candidates for the executive director position. An inventor and pharmaceutical scientist whose career was marked by success and innovation, Busse found the prospect of hiring a new director a daunting one. What were the qualifications for a position that did not yet exist and required a high degree of knowledge across disciplines?

At a meeting one afternoon, Busse showed James Batt a briefcase full of applications, sighed, and asked if Batt would be interested in applying. Batt did, and was flattered to be selected by the committee from a competitive pool of candidates. When Batt started the job, long-time Wisconsin Academy Review editor Walter Scott pulled him aside and said, “My boy, they may call this an academy of arts and letters as well as science. But it’s really, basically, a science academy.”

The long string of Academy successes were indeed mainly scientific in nature. From the earliest days, the Academy had focused its efforts on the sciences. John W. Hoyt encouraged this focus, noting that “a majority of members proposing to render active service in the work of investigation are especially fitted to labor in some branch of the natural and physical sciences.” As the Academy’s scientific reputation grew, so did its scientific membership, thereby stoking the emphasis on science in Academy programming.

Nonetheless, Academy members had been suggesting for decades that the Academy become more active in the arts and letters—both to better represent the founders’ vision and to appear more accessible to an increasingly humanities-aware public. Mark Ingraham, an Academy member and storied UW–Madison professor of mathematics, wrote eloquently in the Wisconsin Academy Review about the power of multidisciplinary education: "We need humanists who understand the physicists, and botanists who read the poets, and all these responsibly interested in the community and its expression in government. … If we live in only one intellectual cell, we live in a prison. … Men must unlock the gates of knowledge and we must choose to walk freely."

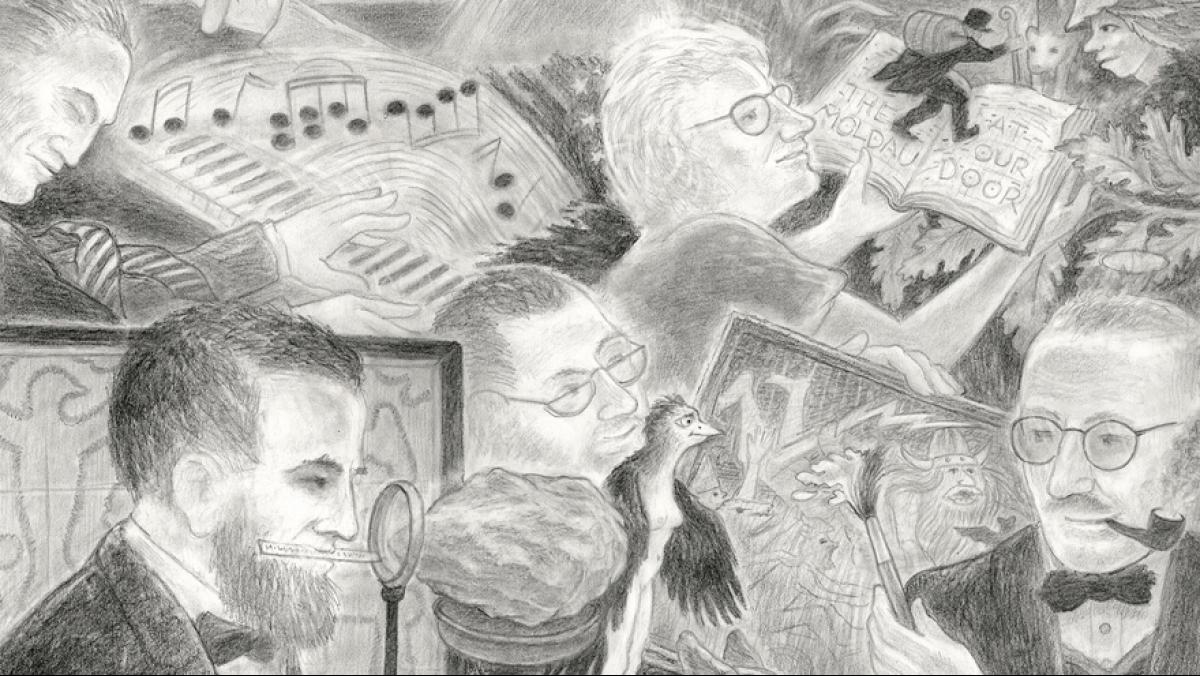

The product of a liberal arts education, Batt understood the power of the arts and humanities to bring people together for a shared experience. With funding from the Steenbock endowment and the Steenbock Center as a home base, Batt began to exhibit Academy members’ artwork on the Center’s walls and in the pages of the Wisconsin Academy Review. His first exhibit was of “The Little Drawings of Norman Olson.” An executive at Northwestern Mutual, Olson was a member of the Academy Board and former President who was, according to Batt, “as at home with arts as he is the sciences.” The drawings—plants and insects, clearly rendered and true-to-life—delightfully bridge Olson’s scientific interest and his artist’s eye.

Batt also started Evenings at the Academy, a series of talks spanning a wide range of topics of interest that brought Academy members into the Steenbock Center to mix and mingle. As editor for the Wisconsin Academy Review, Batt began incorporating poetry and fiction into the magazine and choosing powerful art for the cover. Finally, Batt connected with other nonprofit organizations, like the Wisconsin Phenological Society and the Wisconsin Society of Poets, to build a network of affiliates with whom the Academy could collaborate. These efforts by Batt helped to establish the arts and letters as central to Academy programming, and they inspired future executive directors to continue in this tradition.

Over the intervening decades as opportunities arose to take on new science, arts, and letters projects, various Academy programs expanded in these directions. For instance, the Junior Academy began hosting workshops on writing and art, and including writing presentations in its summer field trip programming. Executive Director LeRoy Lee, who had previously directed the Junior Academy, secured National Science Foundation funding for various educational programs throughout the 1980s and 1990s, some of which trained teachers in pedagogy and sciences skills.

In 1982, the Academy developed the Fellows Award to honor elected individuals whose work has improved the lives of Wisconsin citizens and contributed to our cultural life. Fellows are invited to participate in Academy programming, which provides opportunities for them to connect more directly with Academy members and the public.

In 1994, the Academy established annual poetry and fiction writing contests, which to this day remain open to all residents and provide cash awards and publication to emerging and established writers from across the state. In 2011, the Academy took over the Wisconsin Poet Laureate program after it was unceremoniously removed from the annual state budget by then-Governor Scott Walker.

Today the Academy hosts a handful of intimate gatherings at the Steenbock Center and has rotating exhibits on display year-round in an office that holds ten staff members. However, much of the Academy programming that touches the lives of Wisconsin residents today happens well beyond the walls of 1922 University Avenue.

Serving Wisconsin People

With more interdisciplinary programming, the Academy has more opportunities to invite public participation in both the programs themselves and in the Academy through membership. Whereas in the past, membership in the Academy came through election only, by 1994 the Academy had opened membership to anyone and everyone.

By the year 2000, the number of scholarly journals had expanded dramatically. With so many more outlets through which Wisconsin scientists, artists, and writers could share their research with a global audience, the Academy ceased publication of Transactions. Significantly, the last issue in 2001 was devoted to papers presented at an Academy forum titled, Genetically Modified Foods: Risks, Rewards, and Realities. The focus on the timely and controversial subject represented a new and expanded leadership role for the Academy in bringing communities and experts together to address issues of statewide concern. In the years since, a series of large-scale public initiatives known as The Wisconsin Idea at the Wisconsin Academy (today’s Wisconsin Strategy Initiatives) has brought together hundreds of citizens to discuss water quality, farming and rural life, and other issues that affect our quality of life in Wisconsin.

The end of Transactions also brought about a renewed institutional commitment to the Academy’s quarterly magazine. In 2004, under the guidance of editor Joan Fischer, the Academy redesigned the Wisconsin Academy Review to appeal to smart but not necessarily academic audiences. Changing the name to Wisconsin People & Ideas, Fischer and her colleagues sought to create a record of contemporary Wisconsin thought and culture that could also generate excitement around the big ideas the Academy was exploring across its programs.

Looking to further diversify the suite of mechanisms for reaching broader public audiences in the early 2000s, executive director Bob Lange appealed to the Academy Board to join in the development of a grand new arts center in downtown Madison. With the opening of the Overture Center for the Arts in 2004, the Academy had found a much larger public venue for its creative and engaging programming. The Academy opened the James Watrous Gallery, a noncommercial gallery that features artwork by Wisconsin artists, and began hosting Academy Talks, a series of presentations by experts across myriad fields in Overture Center spaces like the Wisconsin Studio and Capitol Theater. Though developed in Madison, these Academy Talks were often presented in other communities across the state and are available online and on-air through PBS Wisconsin.

Time and again, the Academy has risen to meet new challenges. Because of this, the organization has grown into a more balanced, more public-facing entity that puts the people of Wisconsin first in all of its endeavors. In this way, the Academy serves as a bridge between scholarly life in Wisconsin and the everyday world of its citizens. With its focus on translating and sharing ideas between these two worlds, the Academy is well poised to meet the needs of the future.

Under the direction of Jane Elder, the Academy strives to be a place for people to connect with experts and learn from each other. Elder says people often tell her about how the art in the James Watrous Gallery sparks their imagination, the stories in the magazine and Academy’s public talks keep them informed, and the long-term initiatives addressing climate and water issues provide them hope for a sustainable future. Today’s Academy programs are meant to make us proud of Wisconsin, and they are specifically designed to support learning and discovery for people of all walks of life.

The Academy is also working to increase statewide access to these programs, which are constantly in demand, and to touch more lives; to inspire more emerging writers, scientists, and artists; and to foster more civil dialogue. This is the Academy’s vision for a brighter future inspired by Wisconsin ideas.

In 1981, Academy Board President Reid Bryson acknowledged that “the challenge [today] to the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts & Letters is greater than it was in 1870.” Bryson was a climatologist who was one of the first to consider the effect of global climate change on humans. Recalling how his weather predictions were ignored and troops placed in harm’s way during his time at the Army Air Corps Weather Service during World War II, Byson was well aware of the staggering consequences of anti-intellectualism. His observations from nearly forty years ago feel prescient in our current era of anti-intellectualism and incivility: "Let us mobilize our efforts to maintain the Wisconsin tradition of an enlightened citizenry as we face a future of rapid change, in a crowded world full of unknowns. With knowledge we can reduce the uncertainty and make Wisconsin an even better place to live."

Author’s Note: Individuals involved in the success of the Academy over the past 150 years are too numerous to mention. While a few are named here, it is impossible to do justice to the many who have contributed their time, energy, and dedication to advancing the Academy’s mission. On behalf of the Academy, this author would like to thank those who through their efforts over the years have honored this organization and served the people of Wisconsin. We recognize your contributions and thank you for your efforts to support the Academy’s mission: to create a better world by connecting Wisconsin people and ideas.