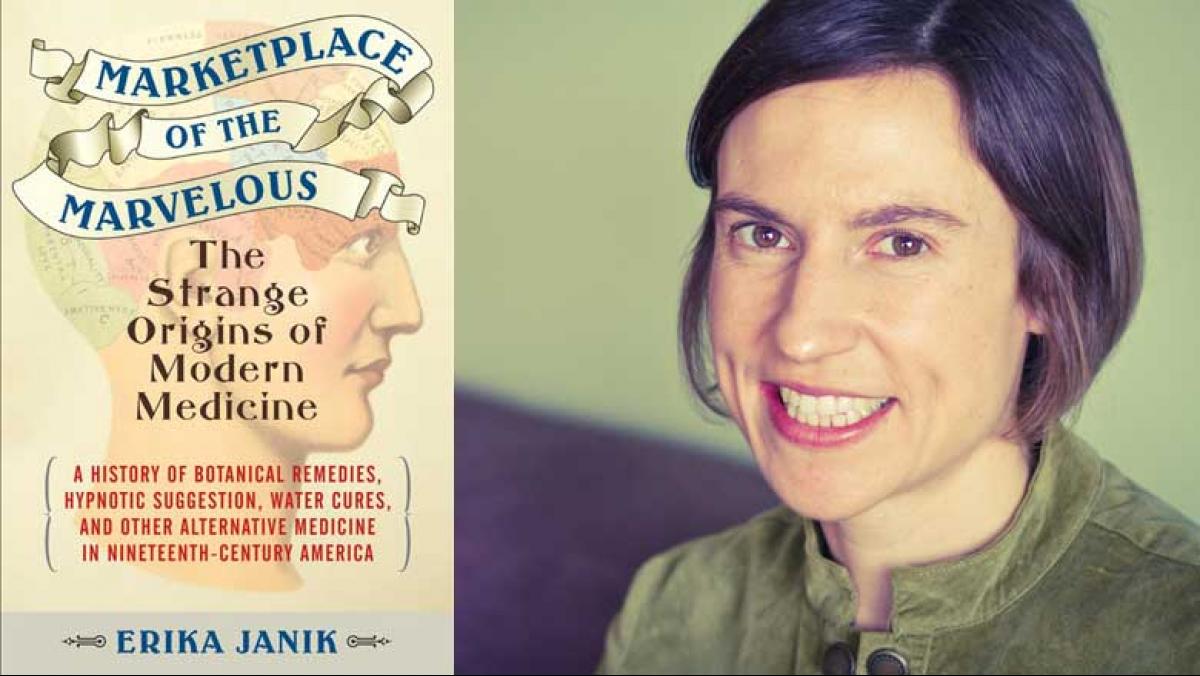

In Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine, Erika Janik traces the development of alternative (or “irregular,” as it was known then) medicine in nineteenth century America. Chapters chart the rise, decline—and, in some cases, resurgence—of botanic medicine, phrenology, hydropathy, homeopathy, mesmerism, patent medicines, and osteopathy. Throughout the book, Janik draws surprising connections between these varieties of irregular medicine and current scientific thought.

She begins the book with a description of her own sense of wonder at finding her great-grandmother’s 1916 certificate in water therapeutics from The Kellberg Institute for Hygiene, Massage, and Medical Gymnastics. Janik, the driving force behind Wisconsin Public Radio’s Wisconsin Life, did what any author of four award-winning history books would naturally do upon encountering an intriguing question: she researched.

Janik found that doctors at the time had belittled the idea of medical gymnastics, what we would today call exercise. But the gymnastics system to promote health and healing developed by Swedish immigrant Per Henrik Ling became quite popular among independent healers of the day. Janik discovered that Ling, who developed a method of medical calisthenics after noticing how his own daily exercises helped to heal joint injuries, “is the Swede behind Swedish Massage.”

“These weren’t the stories I was used to hearing,” Janik writes after offering other examples of irregular-yet-familiar medical treatments. “Most accounts of early American medicine focus tightly on embattled doctors valiantly protecting the public from harmful—and even deadly—medical charlatans and quacks. The nineteenth century was not called the ‘golden age of the quack remedy’ for nothing, right?”

During this period, she goes on to tell us, professional doctors treated patients by bleeding them, blistering them, sweating them, and inducing vomiting. These methods were called “heroic medicine.” Many doctors and their patients believed that a strong visceral reaction was a sign that the administered remedies were working. On top of these painful and largely unsuccessful methods, paying a visit to a doctor was expensive and, in rural areas, could require hours of travel.

The nineteenth century was a tumultuous time in America. The era spawned utopians, abolitionists, prohibitionists, public school supporters, champions for women’s rights, and other advocates for social reform. The Second Great Awakening swelled Baptist and Methodist congregations. With an expanding frontier, waves of immigrants, and money to be made, social mobility increased dramatically.

All of this rapid social change created fertile ground for new ideas and an emerging, American do-it-yourself spirit in the realm of cures and pain relief through a proliferation of irregular medicine options. Hydropathy used cold baths, wet bandages, and steam baths to wash away disease. Phrenologists “read” the bumps and depressions on people’s heads to determine character traits and provide guidance on how to improve negative ones. Osteopaths believed that blockages in blood vessels caused disease and deformity.

Humility doesn’t seem to have been a trait of most of these irregular medicine originators. Many of them claimed that their system was the remedy for all diseases and refused to allow their disciples to change any aspect of it, despite a variable record of success. The irregular systems Janik describes grew in popularity, drawing millions of adherents. Many of them started professional associations and schools. By the end of the Civil War, an increasing number of legitimate doctors were changing their methods to regain patients lost to some of these systems.

But it wasn’t all quackery. Again and again throughout the book, Janik shows that despite being belittled by the medical establishment at the time irregular medicine gave us some useful elements that we rely upon today. Some irregular medicine practitioners encouraged new scientific approaches to testing medical treatments and explored the power of suggestion or brought to light new concepts of cognition. Others decried the idea that remedies were meant to be painful, and touted the benefits of good diet, exercise and cleanliness to ward off disease.

Botanic, patent, and homeopathic medicine were ideal systems for in-home use, and women, as the center of home life, were central to the irregular medicine movement. Many women were in fact respected experts in their fields. For instance, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound was an early and best-selling American patent medicine. Founded in 1851, the American Hydropathic Institute began churning out men and women graduates in almost equal proportion. Where the Massachusetts Homeopathic Medical Society admitted women in 1870, the American Medical Association prohibited admission of women until early in the twentieth century.

Scientific discoveries in the last decades of the 1800s—including germs as causes of infection, the importance of sterile surgery, X-ray imaging, and others—helped to further shift the site of health care out of the home and into the hospital. As such, the irregular medicine system lost much of its momentum and most of its adherents.

Janik closes the book by enumerating the many victories and discoveries of irregular medicine that regular doctors had financial and professional incentive to marginalize. In Marketplace of the Marvelous: The Strange Origins of Modern Medicine, she provides a much-needed corrective to our understanding of health care in this period of American history and a lens through which we can and should view emerging medical treatments.