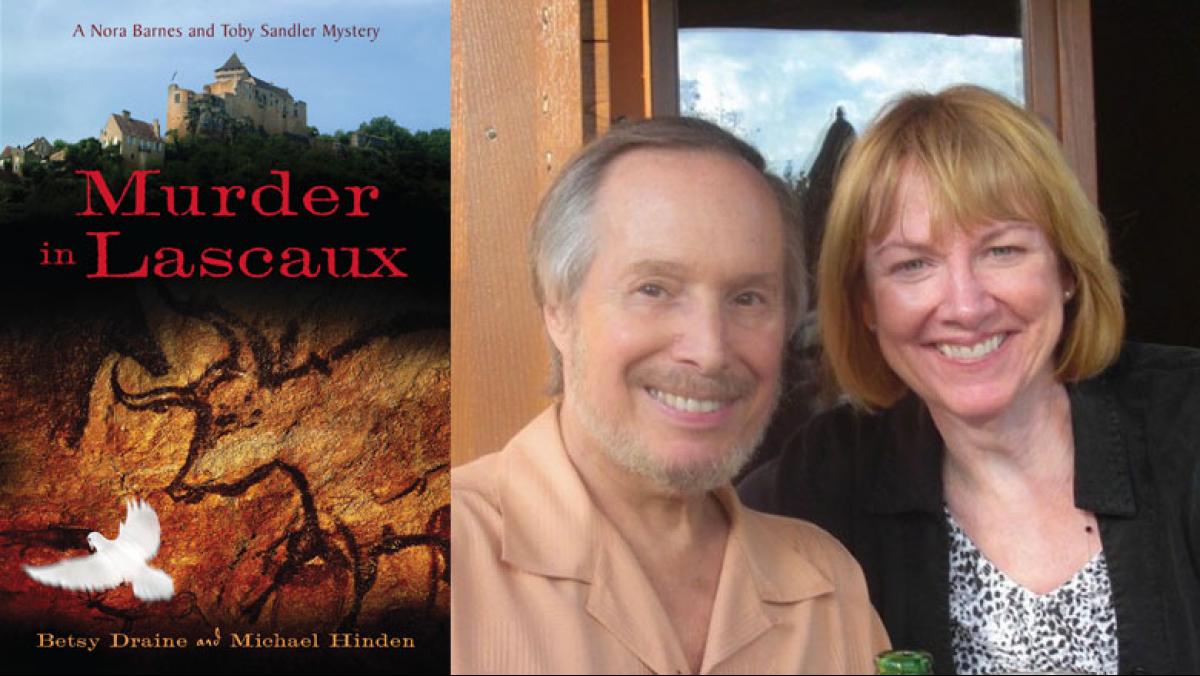

Readers who remember Betsy Draine and Michael Hinden’s joint memoir, A Castle in the Backyard: The Dream of a House in France (University of Wisconsin Press, 2006), and The Walnut Cookbook (Ten Speed Press, 1998), written by Jean-Luc Toussaint but translated and edited by the couple, will find this latest effort familiar territory.

Murder in Lascaux is a mystery novel—the first the two have written together—full of mayhem and intrigue, set in the Périgord region of southwestern France. We’re back in their old neighborhood, tearing up and down the Dordogne River Valley, taking cooking classes at the fictional Château de Cazelle, visiting magnificent real-life towns like Domme and Sarlat, and hanging out in a café in Castelnaud, the village where Draine and Hinden once spent their summers before they decided to sell their property. In short, we’re home.

We’re also in the “home of man,” the cradle of French civilization, for Lascaux is one of the “wonders of the world.” It’s the place where nearly 20,000 years ago, Paleolithic man lived and drew on cavern walls. As Draine and Hinden imagine Lascaux, it’s not just the setting for extraordinary images of colored bulls and horses, but for murder, too.

At Lascaux, we meet the book’s two heroes, Nora Barnes and Toby Sandler, who bear a suspicious resemblance to the authors. Nora is a professor of art history (Draine is a UW–Madison professor emerita of English) and Toby is an antiques dealer (Hinden is also a UW–Madison professor emeritus of English and, until recently, the owner of a home gallery, Art in the Afternoon, specializing in 19th and 20th century paintings).

Nora and Toby—surely the choice of her name is not accidental—remind one of Nick and Nora Charles, the protagonists in Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man. The only thing missing as our unlikely detectives poke their noses into all the wrong (or right, actually) places is a dog. Or perhaps Nora and Toby knew better and left the pooch back in the States.

Nora is in the Dordogne to do research on an obscure French painter, Jenny Marie Cazelle, and to take cooking classes led by the painter’s relative. Toby, along for the ride, goes antiquing in the afternoons while Nora is busy reading in the château’s library. It’s on a guided tour of the original Lascaux caves, even before the two arrive at the château, that a member of their small group is summarily done in by garroting. In real life, Lascaux is closed to tourists. Nora and Toby were given the tour because they have friends in high places. (Draine and Hinden were able to visit the caves years ago when entrance to the public was still permitted. How fortunate for them. I had to settle for the nearby replica, Lascaux II.)

Scary stuff ensues: late-night walks along high cliffs, shadowy trips into dusty attics, a second murder in the dark recesses of another cave, and poisonous mushrooms in omelets. There’s the discovery of a secret society inspired by the Cathars, a 12th century French religious sect, and skeletons in several family closets, not to mention the inquiries made by a French detective reminiscent of Georges Simenon’s Maigret.

Draine and Hinden are too smart, too good-humored, and too smitten with French culture not to weave all these threads expertly into their book. And that’s what gives it its “legs.” For what emerges across the pages is not a tale of derring-do or cooking school menus, spirited and delectable though they may be. (Forget the omelets and opt for the magret de canard, purée of parsnips and apples, and ice cream bombe for dessert.) It’s the reflections on French art and history, the sobering stories not only about the demise of the Cathars (state-sanctioned murder on a large scale), but also about how two devastating wars have left wounds on several generations of French families. Murder in Lascaux may seem as frothy as a café crème but it’s a substantial repast.