“Who’s native and who’s been introduced?” asks a character in Chris Fink’s story, “The Bush Robin Sings.” The question in many ways fits tidily into the other stories within his new collection, Add This to the List of Things That You Are. Though the stories all link to Wisconsin, directly or tangentially, the strongest connection between them is their exploration of male belonging and alien-ation—especially when their male subjects find themselves in the places that raised them.

“Whistle or Lose It,” the opening story in the collection, features Timothy, returned home for his sister’s wedding in rural Blue River, Wisconsin. He’s an outsider from the moment he shows up late to the pig roast. What follows could be considered toxic masculinity on steroids. Timothy fits in neither with the men tending the Roast-a-Shoat nor the women fussing over “the fixin’s.” As the beer flows, the old nipple-twisting, “say uncle,” bullying-big-brother games begin and escalate with bloody consequences. “Difference,” Fink writes, “is like a scab that must be worried until it bleeds.” And bleed it does.

The author continues his exploration of alienation and mascu-line culture in “Cubness.” Cleverly (and courageously) using the first-person plural point of view, Fink puts the reader smack-dab in the heart of a small-town group of friends in the big city for a Cubs game. We take cash out of the bank and “in Chicago we appear to spend it freely because we don’t want to look like cheap hicks to the people of Chicago. […] Each twenty peeled from our roles and blown in the windy city of Chicago hurts us, though we don’t make it known.” These guys pass the day pretending to be big-spender Cubs fans, just a little younger and more urbane than they actually are. In truth, they fool no one—least of all themselves.

Lest we think the male psyche only concerns itself with meat, beer, and sports, Fink introduces us to Graves, a frustrated writer and professor who, “aside from e-mail and copious marginalia on student papers, […] hasn’t written a thing in three years.” Much to his chagrin, and that of his literary agent, Graves’ novella isn’t receiving any interest from publishers. “It would be nice, the agent had said, if his book were larger. Every artist must question the size of his gift.” Instead of finding e-mails from interested publishers, all Graves receives are ads for male enhancements. An amusing coin-cidence or message from the universe? Either way, it’s hard to miss the humor here.

Other stories take the reader to Spain, Russia, California, and beyond. In the “Geritol Valley” of Arizona, the main character named Coyote, is trying to earn his own “green card” through unusual—and brutal—means.

In the final story of the collection, we revisit Timothy, who has settled in Milwaukee in an effort to shed his rural roots. Instead of finally finding his place in the world, however, Timothy faces different challenges to his identity. Rather than rising above his origins, he leans on the old code that raised him. You can take the boy out of Blue River, but, … well, you know.

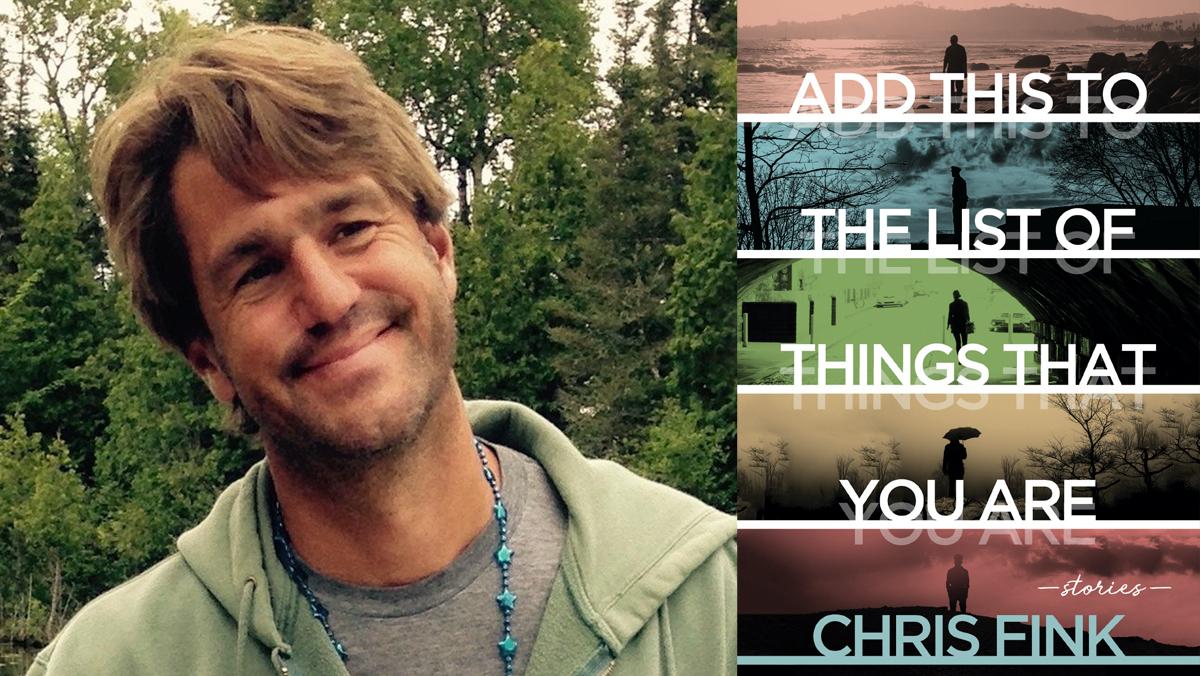

One of the great joys of this collection (and there are many) is the sense that each reading is more expansive and layered than the last. This not only reflects Fink’s chops as a short story writer but also his trust in his readers as co-creators of meaning. Undoubtedly, his career as a professor of creative writing and editor of the Beloit Fiction Journal contribute to his smart, thought-provoking writing. His environmental journalism background also shines through in stories with a strong sense of place. This is a collection you’ll want to savor, story by thought-provoking story.