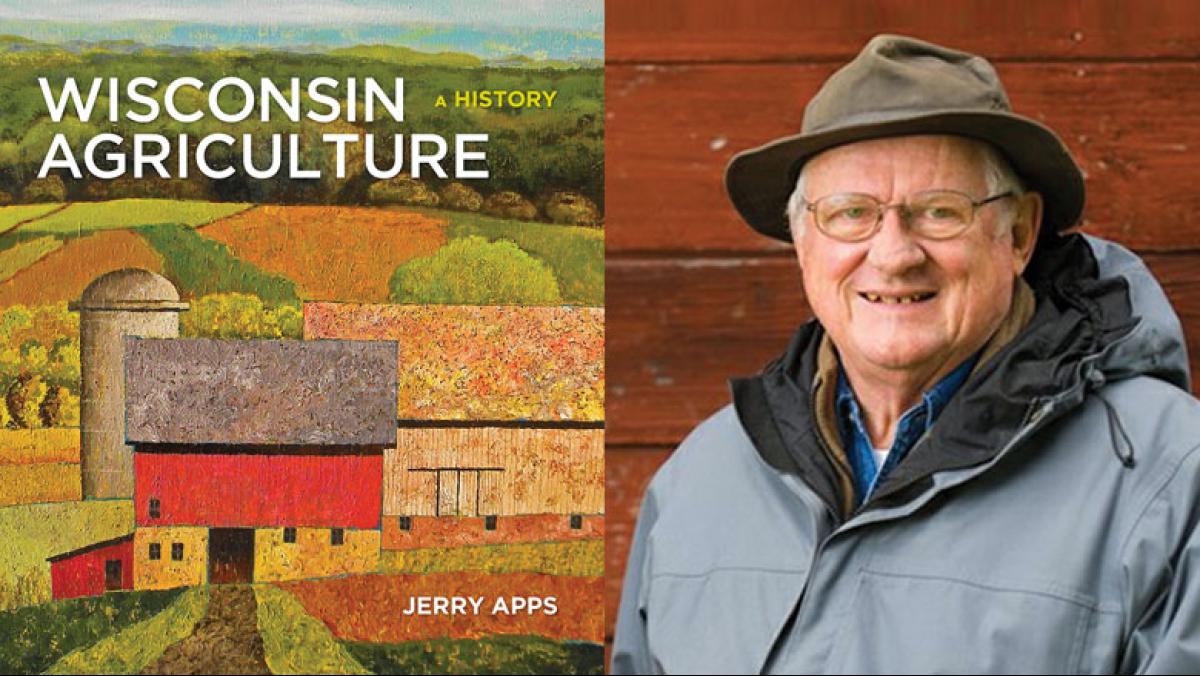

The voluminous new history of Wisconsin agriculture by author and historian Jerry Apps is a pleasure to consume, learn from, and enjoy.

Sorry, but this is as close to critical this review is going to get. As many know, Apps is a master storyteller and prolific writer, comfortable in rural fiction and nonfiction realms. It could be argued he’s the best-ever Wisconsin rural folklorist.

This book, however, is something unlike anything Apps has attempted in his long and fruitful career. A richly-illustrated release from the Wisconsin Historical Society Press, Wisconsin Agriculture: A History is a concise and informative chronicle of this place called Wisconsin.

A work of this sort is a challenge for any writer or historian, evidenced by the dearth of agricultural history titles with a Wisconsin slant. Perhaps the telling of the story is so difficult it has dissuaded others from taking a swing. There are a few nuggets, including Robert Gard’s enduring yet ethereal My Land, My Home, My Wisconsin: The Epic Story of the Wisconsin Farm and Farm Family from Settlement Days to the Present (1978) and Joseph Schafer’s comprehensive A History of Wisconsin Agriculture in Wisconsin (1922). But a true history book like this one requires a level and depth of understanding and source materials few possess. A farm-born Wisconsin native, Apps has lived it all along—farmer, educator, storyteller, and author.

Apps follows some of his familiar folksy pathways in the telling of this history, and natural history, of farming in Wisconsin. But he does so in a compelling way that might at once appeal to an array of audiences, from Wisconsin history buffs to agricultural devotees to those with only minor interest in agriculture. Indeed, the book’s strengths are its broad appeal and the way it moves smoothly and efficiently through centuries of developments. Wisconsin agriculture is varied, from cows and corn and soybeans, to vegetables, fruit, and an array of specialty crops. Yet each is a story in itself.

Wheat dances in the wind in early chapters, cows and corn take their place in others. The immigrants who raise them come in their own waves, bringing their traditions, customs, and beliefs. Machines keep getting better, and so does the cheese. Education drives innovation as agriculture achieves and maintains a huge swath of Wisconsin’s economy, challenged though it always is by nature and economics.

Apps tells the good stories and the tough ones, from cranberry festivals to migrant workers marching for rights. Some may wish for more detail, as in Wisconsin’s ground water challenges, but, given the task at hand, Wisconsin Agriculture doesn’t have time to linger too long on these complicated challenges of the commons.

The author’s storytelling skills are complemented by the quiet hands of the Wisconsin Historical Society Press editors and designers who composed the pullouts, sidebars, photographs, and graphics that steer the book in the friendliest of ways. The sum of all accomplishes a rare feat for books of history: You can pick up Wisconsin Agriculture, open to almost any page, and be instantly drawn in.